Personal Wealth Management / Market Analysis

After the Shortest Bear Market Ever, How Long Can the Bulls Run?

In our view, a bear market’s length doesn’t predict how far the next bull market will run.

How long can this bull market—a prolonged period of generally rising equities—last? That is a question we have seen many financial commentators consider lately, seemingly with the underlying presumption that the shortest bear market (a fundamentally driven equity market decline of -20% or worse) of all time, followed by the lightning fast recovery to prior highs, raises the likelihood that this will be a short bull market.[i] Another consideration that may also be fuelling this mentality is that this year’s bear market acted more like an oversized correction (a short, sharp sentiment-driven decline of roughly -10% to -20%) than a traditional bear market—and it all follows history’s longest bull market.[ii] But in our view, there is no realistic way to assess how long this bull market will last—you must assess conditions as they evolve. One thing, however, is clear based on our research: Age and the prior bear market’s length don’t really mean anything. Our study of history shows all bull markets end one of two ways: when investors have run out of worries and developed irrationally high expectations, or when something wallops the expansion before its natural peak.

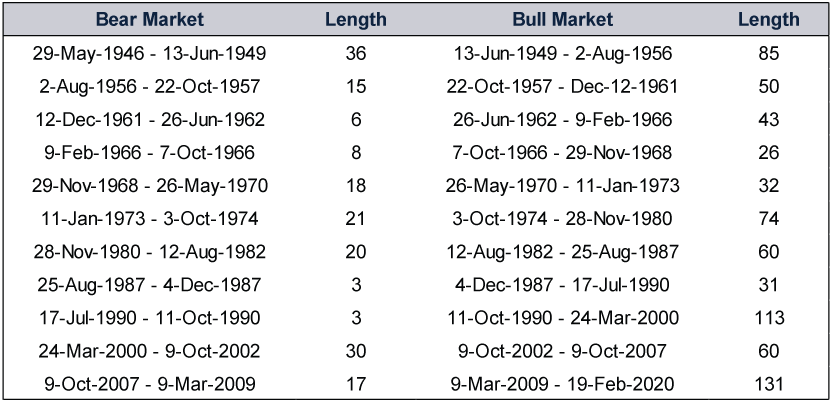

Consider Exhibit 1, which shows the length of every bull market—and ensuing bear market since WWII. For this, we used the S&P 500 Index in US dollars due to its lengthy history of reliable data. As you will see, the length of bear markets doesn’t mean much. Prior to 2020, the two shortest bear markets on record were 1987’s and 1990’s. The bull market that followed 1987’s crash was relatively short at 31 months. But 1990’s bear market was almost exactly as short. The bull market that followed the second was the 1990s’ boom—at 10 years, it is history’s second-longest. One short, one long, no pattern, in our view.

Exhibit 1: S&P 500 Bear and Bull Market Lengths (in Months)

Source: Global Financial Data, Inc., as of 24/3/2020. Length is rounded to the nearest whole month. Presented in US dollars. Currency fluctuations between the dollar and pound may result in higher or lower investment returns.

The bull markets above came in all shapes and sizes, but our research shows they all ended in one of the two ways: either when euphoria (overly optimistic investor sentiment) made expectations for things like future corporate profits or sales unattainable or when hit by a huge, unseen negative. In March 2000, August 1987 and most others, we think euphoria ruled the day. Investors generally seemed to behave as if equities’ rise would last forever, and much of those eras’ financial commentary overlooked or explained away any indicators hinting at negativity ahead. March 2000 was the height of the Internet-driven dot-com boom—the new economy, as one US magazine headline described it, when the boom and bust economic cycle was declared dead and financial commentators sought new terms for economies that only grew. With the so-called Millennium Bug (the issue with a computer dating format that, according to many, threatened to turn digital calendars back to 1900 at the turn of the millennium and shut down the electrical grid, amongst other disruptions) having come and gone, many thought the coast was clear for more Tech-led economic growth and bull market. Many commentators we followed at the time overlooked the declining Leading Economic Index (an index of 10 economic indicators that aims to predict future economic conditions, as measured by The Conference Board) and inverted yield curve (a visual representation of a single issuer’s interest rates across a range of maturities), not to mention the flood of IPOs (initial public offerings, in which a company sells its shares on the open market for the first time) by companies with no profits, no sound business plan and deep operating losses. We think euphoria blinded investors to all of these, and a bear market began.

Bull markets that didn’t end in euphoria ended when a huge negative burst on the scene, surprised the world and walloped the global economy hard enough to knock a few trillion pounds off global gross domestic product (GDP, a government-produced estimate of economic output), rendering recession. In October 2007, our analysis shows it was America’s imposition of the mark-to-market accounting rule (which required banks to mark assets on their balance sheet to their current market value) to rarely traded assets banks never intended to sell, forcing them to take paper losses whenever a hedge fund or other entity sold similar holdings at rock-bottom prices. According to one prominent observer’s analysis, this vicious cycle of writedowns and fire sales eventually transformed about £150 billion worth of actual loan losses into nearly £1.5 trillion of exaggerated and unnecessary writedowns.[iii] In this year’s bear market, we think the wallop was the global lockdown aimed at containing the spread of COVID-19, which caused the deepest and most rapid economic contraction in modern history.

For something to qualify as a wallop, our research shows it must be huge—trillions of pounds’ worth of huge—and surprising. The myriad alleged negatives percolating through financial headlines lately don’t count, in our view, because they are either too small, too unlikely or too well-known. In our view, these aren’t wallops in waiting, but the first bricks in this bull market’s wall of worry. As for sentiment, we think most of the investment community is still waiting for the other shoe to drop and economic conditions to worsen, not envisioning perma-expansion.

If you are investing for long-term growth, we think the above is what you need to know when it comes to deciding whether to own equities. If you aren’t in a bear market, you are in a bull market, and capturing bull market returns is vital to achieving market-like returns over time, in our view. In our opinion, whether this bull market expires in two years, three or more shouldn’t make any difference to your asset allocation today. Taking defensive positioning when you are actually early in a bear market can be beneficial, but we don’t think the day to make that decision is when equities are fresh off all-time highs. This year’s notwithstanding, the vast majority of bear markets roll over slowly in our experience, giving investors time to assess the situation carefully and avoid knee-jerk decisions.

So rather than sweat now about how long this bull market might last, we think it is more beneficial to just live in the moment whilst keeping your eye on your long-term goals. If you are in a diversified portfolio tailored to your needs and time horizon, take heart in knowing that equities’ long-term returns include all bull and bear markets along the way.[iv] Whilst we think it is prudent to watch for signs a bear market may be underway, trying to date a bull market’s end before you see them is a guessing game unlikely to yield success.

[i] Source: FactSet, as of 8/9/2020. Statements based on MSCI World Index returns with net dividends in GBP, 20/2/2020 – 16/3/2020 and 16/3/2020 – 2/9/2020.

[ii] Source: FactSet, as of 8/9/2020. Statement based on MSCI World Index returns with net dividends in GBP, 31/12/1969 – 31/8/2020

[iii] Senseless Panic by William Isaac, published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2010.

[iv] Source: FactSet and Global Financial Data, as of 21/2/2020. Statement based on MSCI World Index annualised return with net dividends in GBP, 31/12/1969 – 31/12/2019.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights.

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

See Our Investment Guides

The world of investing can seem like a giant maze. Fisher Investments UK has developed several informational and educational guides tackling a variety of investing topics.