Personal Wealth Management / Market Analysis

British Austerity: A Solution Seeking a Problem

The UK doesn’t have a government debt problem for tax hikes and spending cuts to solve.

Austerity is coming back. That is the warning we have seen from several financial commentators we follow in the wake of Chancellor Rishi Sunak’s speech at the Conservative Party Conference earlier this month. Sunak’s address warned of the need to put public finances “back on a sustainable footing” and stressed the importance of “fiscal responsibility” as UK national debt closes in on 100% of annual economic output (as measured by gross domestic product, or GDP). As he warned against “stacking up bills for future generations to pay,” he seemingly set expectations for tax rises beyond the national insurance contribution increase announced earlier this year—raising the spectre of tougher austerity than Britain experienced in the 2010s. Then, austerity (a general term for measures to reduce the deficit) largely amounted to former Prime Minister David Cameron’s government increasing public spending slower than projected under his predecessor, Gordon Brown.[i] This time, the mere mention of tax rises appears to have inspired warnings of much tougher austerity now and in the future, what with pension and other age-related spending forecast to rise over the long term according to the Office for Budget Responsibility’s projections. Whilst we don’t think it is possible to predict government policy precisely, we do think investors likely benefit from having a clear understanding of the UK’s debt load and its sustainability over the foreseeable future, so let us review.

Whenever financial commentators we follow discuss national debt—whether in the UK, US or elsewhere—they typically focus on the absolute amount outstanding as a percentage of GDP. We can understand the impulse, as large numbers like debt tend to be meaningless without context. Intuitively, the larger a country’s economy is, the more debt it can likely handle. But we don’t think debt-to-GDP sheds much light on whether debt is becoming problematic. For one, it compares two variables with little in common. GDP is what economists call a flow—the amount of activity that occurs in a year, whether measured by spending or production volumes. Debt is what economists call a stock—an amount that accumulates over time. So comparing debt to GDP doesn’t measure like against like.

Then too, the Treasury doesn’t have to repay the national debt every year. Rather, they must pay interest due to investors who own UK debt securities (known as gilts), and they must repay principal on maturing gilts. In years when the government runs budget deficits (i.e., public spending exceeds public receipts), it will generally issue new gilts to replace maturing ones, a process known as refinancing the debt. Therefore, we think the main concern is interest payments and whether the Treasury can afford them. In our view, the most helpful way to do this is to compare interest payments to government receipts.

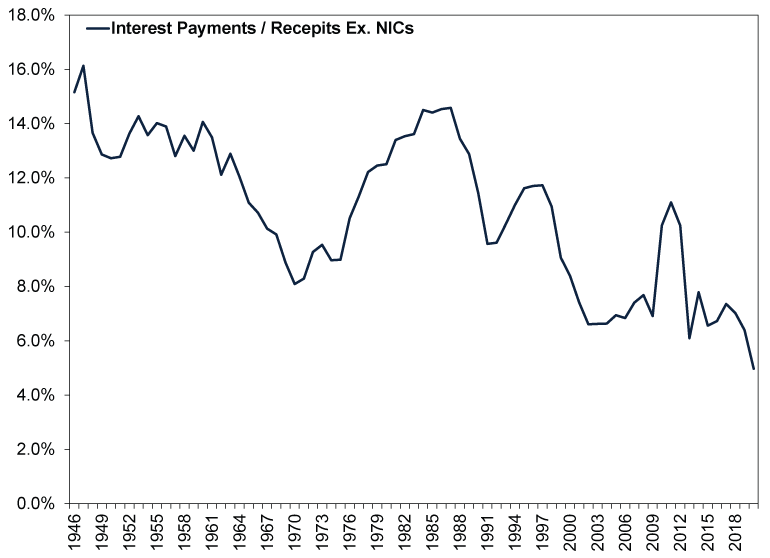

Happily, the Office for National Statistics publishes detailed information on public finances all the way back to 1946, making it easy to see how debt affordability now compares to the past. We do so in Exhibit 1. For interest payments, to match the methodology used in the annual Budget reports, we excluded interest owed on the gilts held in the Bank of England’s (BoE) Asset Purchase Facility (APF), as the BoE returns these interest payments to the Treasury. So our calculation of interest is total interest payments minus interest paid to the Treasury from the APF. For receipts, we think the most meaningful comparison point would be tax revenues, but the ONS’s time series of annual tax revenues begins in 1998. So to have a more meaningful dataset, we downloaded the central government’s annual total receipts and subtracted annual national insurance contributions (NICs). This figure is slightly larger than pure tax revenues would be, but we think it is a useful approximation nonetheless.

Exhibit 1: Interest Payments Are Historically Small Compared to Government Receipts

Source: Office for National Statistics, as of 15/10/2021. Central Government Total Current Receipts, Compulsory Social Contributions (NICs), Total Interest Payable and Interest Receivable From the Asset Purchase Facility, 1946 – 2020.

As the chart demonstrates, despite debt rising significantly last year as the Treasury borrowed more to finance COVID relief measures, interest payments fell to an all-time low share of government receipts excluding NICs. One reason for this is the BoE’s large amount of purchases via the APF, but interest rates’ hitting generational lows also helped. Not only did they enable the Treasury to borrow very cheaply in a crisis, but they also helped it refinance many maturing gilts at lower interest rates, helping reduce the cost of servicing the pre-2020 debt stock.[ii]

The Treasury does project interest costs rising this year, which isn’t surprising given the pace at which public borrowing has continued. In the March 2021 Budget report, the Treasury projected interest payments net of the APF would rise to 7.7% of tax revenue and 6.7% of all receipts excluding NICs. These levels remain amongst the lowest on record. Relative to tax revenues, debt service was at least twice as expensive as it is now for much of the 20th century’s second half, yet the UK never had a debt crisis. It didn’t default and get locked out of international borrowing markets, as Greece, Argentina and others did. The country did go through some tough times, including the Suez Crisis, the post-War era, the Winter of Discontent and the pound’s troubles in 1992. We aren’t dismissing those. But none constituted a debt crisis, which suggests to us that debt is quite far from crisis levels now.

So what would have to happen for debt to become problematic in the future? In our view, one of two things. One, we think the government would need to rapidly increase debt in a very short time again, raising the near-term interest burden. That doesn’t appear likely, based on any of the reports we have seen or from public commentary from either the government or Labour Party leaders.

The other potential path to trouble, in our view, would be for long-term interest rates to jump to sky-high levels and stay there for many years. According to the Debt Management Office, the average maturity of the Treasury’s outstanding debt is about 14 years, which means low borrowing costs are locked in for many years. For that to change, we think the Treasury would have to refinance debt at much, much higher rates for a long while. Not at rates modestly higher than the 10-year gilt’s current 1.09% rate, which is amongst the lowest on record despite this year’s uptick.[iii] In our view, rates would need to be far higher—several times current rates.

Within the foreseeable future—the next 3 – 30 months or so—we don’t think this is likely. Long-term interest rates tend to move globally, and rates throughout the developed world are near historic lows. In our view, negative rates throughout continental Europe drive demand for higher-yielding assets in the UK and US, helping keep rates low in both nations. We do think inflation (a general rise in prices across the economy) affects interest rates, and it is true that inflation is relatively high now.[iv] Yet we also think markets are efficient, meaning they already reflect widely known information—including present inflation and expectations for inflation in the future. Commentators we follow globally warn supply chain issues and high energy costs could spark fast inflation for years on end, which we think renders it likely that markets already reflect high inflation expectations. Therefore, for rates to rise a lot from here, we think it would require more and longer-lasting inflationary pressures than people already project. We don’t think that is likely, considering producers of energy, semiconductors and other currently scarce resources are already ramping up production to fill the shortfalls, according to several reports we have seen in recent months.

Again, we don’t think any of this predicts how the government will adjust spending and taxation in the next few years. Those are political decisions, which defy forecasting. But we do think it demonstrates that austerity is just that—a political issue, not anything necessary to avoid significant debt problems in the foreseeable future. Accordingly, whether or not the Treasury takes severe deficit reduction measures, we don’t view UK debt as a significant economic or market risk.

[i] Statement based on spending figures published in the annual Budget reports, 2008 – 2017.

[ii] Source: Debt Management Office, as of 15/10/2021.

[iii] Source: FactSet, as of 15/10/2021.

[iv] Source: FactSet, as of 15/10/2021. Statement based on Consumer Price Indexes (CPI) in the US and UK and Harmonised Indexes of Consumer Prices (HICP) in eurozone nations. CPI and HIPC are broad measures of prices across the entire economy.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights.

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

See Our Investment Guides

The world of investing can seem like a giant maze. Fisher Investments UK has developed several informational and educational guides tackling a variety of investing topics.