Personal Wealth Management / Politics

Checking In on the Global Minimum Tax

It may be advancing—but at a snail’s pace.

Editors’ note: Given tax policies touch politics, please keep in mind MarketMinder Europe is politically agnostic and never for or against any particular policy. We assess developments solely for their potential market impact—or lack thereof.

Earlier this month, preparing for a planned 2024 rollout, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) issued final guidance on how governments should enact a 15% minimum tax on large companies that 137 countries agreed on in October 2021.[i] This may sound like the much-vaunted Global Minimum Corporation Tax is gathering pace and implementation is at hand. But that impression doesn’t match reality, in our view, and a look at the long and uneven process shows why tax overhauls—even those billed as major once-in-a-generation shifts like this—generally have way less market impact than most think, as we will show with data.

When last we left it almost a year ago, the EU had run into a roadblock, as several low-tax member nations objected to the plan—wanting to see US action before signing on. After a mid-December breakthrough, though, Poland and Hungary dropped their objections and all 27 EU members ostensibly greenlit the proposal.[ii] Now, the OECD is taking the next steps by issuing detailed instructions for incorporating it into governments’ tax codes.[iii]

But, in our view, the OECD’s instructions largely amount to wishful thinking at this point—implementation isn’t at hand, instructions or no—because countries must still vote to enshrine the new code into national law, and none have yet. Even in the EU, its members need to transpose it onto each of their books, meaning they have to pass national parliaments.[iv] We think that is a potentially big hurdle considering the political gridlock we have observed in many parts of the EU (to say nothing of non-EU nations like the UK). The EU wants this done by yearend—stragglers otherwise face the European Court of Justice (ECJ).[v] But national parliaments have withstood ECJ ire before—sometimes for years—before resolution.

Consider Hungary, which was the main objector before December.[vi] Hungary has long been at odds with the EU and its executive arm, the European Commission, as the EU alleges widespread cases of judicial corruption violate its rule-of-law standards.[vii] On these grounds, the bloc froze COVID financial support and other funding starting in 2020.[viii] Now the EU has agreed to partially release the funds if Hungary backs the tax reform and meets other conditions.[ix] We have no idea how Hungary’s Parliament will vote, but given it was willing to spend several years out of compliance, we don’t think it is out of the question to believe it may stall global minimum corporation tax legislation in the hopes of extracting further EU concessions.

Besides Hungary, Switzerland—outside the EU—has expressed reservations about implementing the tax.[x] It faces a June referendum to raise its corporation tax to 15%—for companies with revenues exceeding €750 million (~£660 million)—to meet the global deal’s standards.[xi] Presumably, an agreed failsafe rule could pressure countries to conform to this. Since it allows other governments to collect the difference in their jurisdiction, it could shift revenue non-compliant nations would otherwise get away from them.[xii]

That may seem like an incentive for all participating nations to raise their statutory rates if they are below 15%. But a caveat to the rule also allows countries with below-15% tax rates to collect any such top-up taxes first.[xiii] It may make sense for them to do so. Switzerland could keep its tax rate globally competitive for companies with €750 million or less in sales and get the tax haul from corporations over that threshold via the top-up. Questions also abound about conditions that would tax the largest multinationals (€20+ billion in sales and 10%+ OECD-defined profitability) where they make money versus where they locate their regional headquarters for tax purposes.[xiv] The problem we see here: This runs against long-standing tax treaties, which countries have yet to rewrite.[xv]

And then there is America. Whilst President Joe Biden’s administration—led by Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen—spearheaded the global minimum tax effort last year, even with his Democratic Party’s nominal congressional control, the initiative fell short.[xvi] Senator Joe Manchin, holding the pivotal vote, didn’t agree, as he was reportedly reluctant for America to go first and potentially place its companies at a competitive disadvantage.[xvii] (The alternative minimum corporation tax rate passed separately, though set at 15%, is worlds different from the OECD-supervised initiative, hence adopting the global tax deal in the US would require new legislation.)[xviii] Now, with Republicans controlling the House of Representatives, few policy analysts we follow envisage the US passing the necessary legislation any time soon, which may rekindle objections in other nations worried America wasn’t going to advance it originally.

Like Switzerland (or Hungary), if America doesn’t budge and other countries then take the lead, its qualifying companies could be subject to higher taxes in complying jurisdictions abroad. This wouldn’t take effect immediately, though. The latest OECD guidelines offer a partial reprieve on it through 2025.[xix] And here again: No nation has enacted this plan. It isn’t law anywhere, as the OECD doesn’t make laws.

Anyway, the thinking goes Congress will be more likely to take up major tax legislation when individual tax breaks in 2017’s Tax Cut and Jobs Act (TCJA) expire.[xx] Maybe. But that to us is a bet on both the structure of the US government and the way political winds blow at the time.

Although complicated, with all the moving parts—and carve outs—we think any new tax (if implemented) will likely have far less impact than anticipated. The complication may present headaches to corporation tax departments, but we doubt it would be anything they couldn’t handle. In our experience, corporations are well versed in dealing with complicated tax regulations that span the world. Also, we wouldn’t consider a 15% minimum tax exactly onerous given the vanishingly small number of countries with effective tax rates below that.[xxi] Now, some significant ones do, and taxes moving to where companies earn profits from those lower-tax domiciles could have an impact, in our view, but we wouldn’t overrate it.

For example, whilst Ireland is well known for having a low tax rate (15% next year, up from 2021’s 12.4% effective rate), the European Commission cracked down on profit shifting in 2015.[xxii] Multinationals’ tax-mitigation strategies that book all their European profits in Ireland aren’t as advantageous anymore.[xxiii] Meanwhile, the TCJA changed US corporation taxes to a territorial system—US companies are already paying countries’ taxes on income earned there.[xxiv]

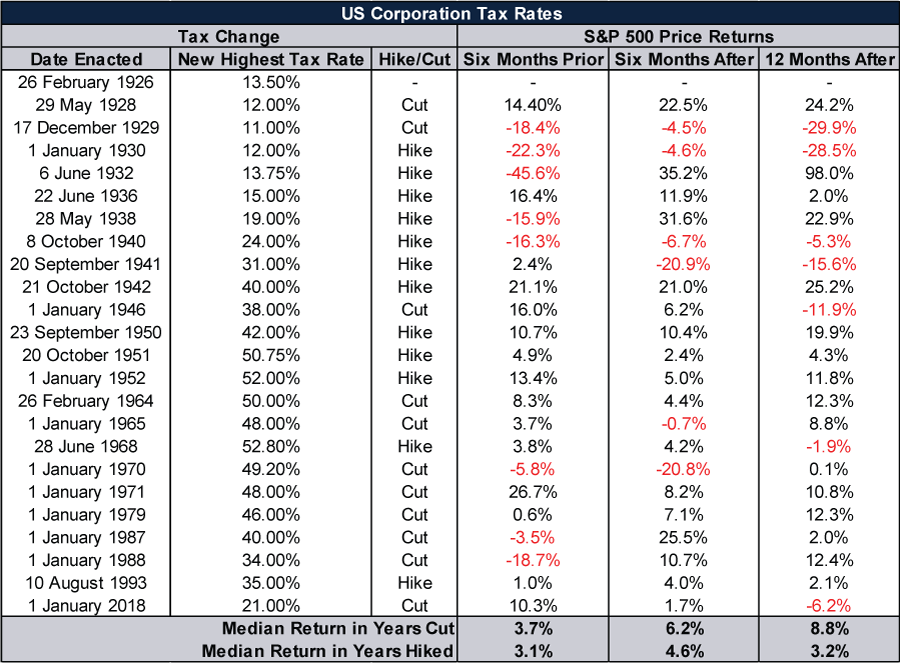

In any event, our research shows tax changes haven’t historically carried big market impact. Take US corporation taxes. Exhibit 1 shows whether cut or hiked, there is no set return pattern to them. We find other factors matter more—like economic conditions. Yes, tax hikes during the Great Depression probably weren’t helpful, but to us, it was the Great Depression that inordinately weighed—which most of post-war history bears out. The other reason why we don’t think taxes seem to sway stocks: They are closely watched, which likely saps their power over markets. That is pretty clearly the case here, in our view, given the vast attention paid to the OECD plan for the last several years.

Exhibit 1: US Stocks Haven’t Been Too Affected by Corporation Tax-Rate Changes

Source: Global Financial Data, Inc. and US Internal Revenue Service, as of 6/2/2023. S&P 500 price returns, 31/12/1925 – 31/12/2018. Data are weekly from 31/12/1925 – 31/12/1927 and daily thereafter. Presented in US dollars. Currency fluctuations between the dollar and pound may result in higher or lower investment returns.

The global tax regime is something we will continue to monitor, particularly for any changes that may yield unintended consequences. But with the long row left to hoe—and lawyering over every inch of it—we don’t see much likely to catch stocks off guard.

[i] “OECD Offers Final Guidance for Global Minimum Corporate Tax,” Staff, Reuters, 9/2/2023. Accessed via US News & World Report.

[ii] “EU Strikes Deal With Hungary Over Ukraine Aid, Tax Plan, Recovery Funds,” Gabriela Baczynska and Jan Strupczewski, Reuters, 12/12/2022. Accessed via US News & World Report.

[iii] See note i.

[iv] “International Taxation: Council Reaches Agreement on a Minimum Level of Taxation for Largest Corporations,” Staff, European Council, 12/12/2022.

[v] “EU Deal Set to Trigger ‘Domino Effect’ for Global Minimum Tax Deal,” Mary McDougall, Financial Times, 18/12/2022. Accessed via the Internet Archive.

[vi] “Hungary Still Opposed To ‘Job Killing’ Global Minimum Tax, Orban Says,” Staff, Reuters, 1/12/2022. Accessed via Yahoo!

[vii] “Viktor Orbán’s Grip on Hungary’s Courts Threatens Rule of Law, Warns Judge,” Flora Garamvolgyi and Jennifer Rankin, The Guardian, 14/9/2022.

[viii] “ECJ Dismisses Hungary and Poland’s Complaints Over Rule-of-Law Measure,” Jennifer Rankin, The Guardian, 16/2/2022.

[ix] See note ii.

[x] “Swiss Finance Chief Sees Country Condemned to Accept Minimum Tax,” Bastian Benrath and William Horobin, Bloomberg, 18/1/2023. Accessed via swissinfo.ch.

[xi] “Switzerland Will Apply Minimum Tax – With or Without the US,” Staff, swissinfo.ch, 18/1/2023.

[xii] See note v.

[xiii] “Unpacking Pillar Two: domestic minimum taxes,” Elizabeth Keeling, Bezhan Salehy and Rhiannon Kinghall Were, Macfarlanes, 11/4/2022.

[xiv] “Progress Report on Amount A of Pillar One Frequently Asked Questions,” Staff, OECD, July 2022.

[xv] See note x.

[xvi] “Yellen Says U.S. Aims to Move Ahead With Global Minimum Corporate Tax,” Andrea Shalal, Reuters, 16/7/2022. Accessed via US News & World Report.

[xvii] “Global Tax Deal Imperiled by Manchin’s Balking at Minimum Corporate Levy,” Brian Faler, Politico, 15/7/2022.

[xviii] “Part One: FACT’s 2023 Springboard for International Tax and Tax Transparency Reforms,” Ryan Gurule, Financial Accountability & Corporate Transparency, 1/2/2023.

[xix] “OECD Gives U.S. Companies Reprieve From International Minimum Tax,” Staff, MSCI, 6/2/2023.

[xx] “EU’s Tax Move to Swipe Revenue From US Unless Congress Follows,” Christopher Condon, Bloomberg, 16/12/2022. Accessed via Yahoo!

[xxi] Source: OECD, 6/2/2023. Effective tax rates, 2021.

[xxii] “Fair Taxation: Commission Presents New Measures Against Corporate Tax Avoidance,” Staff, European Commission, 28/1/2016. “Global Tax Deal Inches Closer as Holdout Ireland Agrees to Sign Up,” Silvia Amaro, CNBC, 7/10/2021. Also see note xxi.

[xxiii] “Ireland to Close ‘Double Irish’ Tax Loophole,” Henry McDonald, The Guardian, 13/10/2014.

[xxiv] “A Hybrid Approach: The Treatment of Foreign Profits under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” Kyle Pomerleau, Tax Foundation, 3/5/2018.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights.

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

You Imagine Your Future. We Help You Get There.

Are you ready to start your journey to a better financial future?

Markets Are Always Changing—What Can You Do About It?

Get tips for enhancing your strategy, advice for buying and selling and see where we think the market is headed next.