Personal Wealth Management / Economics

Inside China’s July Slowdown

Headlines’ reaction to some disappointing economic data seems overblown to us.

Was it Delta, flooding or a deeper economic problem? That is the question several financial commentators we follow scrambled to answer this week, after China’s July economic data missed expectations. Retail sales and industrial production grew at what most other nations would likely consider a fine clip (8.5% y/y and 6.4% y/y, respectively), but both slowed sharply from June.[i] So did exports and imports, released earlier this month. Most of the commentary we read arrived at the conclusion that the escalating battle with the Delta variant and flooding in central China had only a modest impact on July’s results, with deeper troubles explaining the rest. We agree the tragic floods and Delta alone likely don’t explain the disappointing data, but we don’t agree with the implication that a faltering China is about to impede the global recovery from the pandemic or present a material headwind to the publicly traded companies deriving significant revenue there (which includes several FTSE 100 names).

For a few months now, the general consensus amongst commentators we follow has held that China’s economic recovery rests on heavy industry, with consumers and services struggling. That allegedly points to weak domestic demand, as factory activity continues getting a boost from the developed world. In our view, that explanation is too simple and ignores all of the distortions at play within China and globally right now.

Central flooding and the Delta variant of the virus that causes COVID-19 are two of those distortions, of course. Zhengzhou, the capital of flood-ravaged Henan province, is one of the country’s major manufacturing hubs, which we think likely explains industrial production’s slowdown partly. Flooding also complicated the city’s efforts to curtail a Delta variant outbreak, but other major cities (e.g., Nanjing, Wuhan, Yangzhou and Zhuzhou) have all reportedly entered partial lockdowns in recent weeks, likely curbing economic activity.[ii] Outbreaks also closed multiple ports this summer, hampering trade. Then, of course, there is also the global shortage of several raw materials, which various industry surveys show has hit manufacturers in China and the developed world alike.[iii]

Beyond current events, we think there is another, longer-running distortion: the base effect. Or, said differently, the denominator in the year-over-year growth rate calculation. China does release seasonally adjusted month-over-month growth rates, and those got some attention Monday as well, but most analysts we follow think the seasonal adjustments are too immature for the data to be at all reliable. That leaves year-over-year data (the percentage change between a given month and that same month a year prior), which mathematically invites considerable skew from a year ago. COVID and lockdowns first started registering in Chinese data in December 2019, when industrial production tanked.[iv] The pain lasted through the Lunar New Year holiday, and retail sales bottomed out that March.[v] The next several months saw a strong recovery thanks to the twin tailwinds of pent-up demand at home and a lockdown-ravaged developed world hungry for all manner of Chinese-made goods, which we think set an artificially high bar for year-over-year data to clear now.

To strip out the distortions, China’s National Statistics Bureau began including two-year growth rates for all major monthly data in February, the first release of 2021. (China always combines January and February data due to the Lunar New Year holiday week’s shifting timing.) That is, they report the percentage difference between a given month and that same month in 2019, on the presumption that 2020 was a lost year. The logic there is debatable, in our view, but for fun we pulled the two-year growth rates for retail sales this year. After doubling from 6.4% in January/February to 12.9% in March, it has slowed steadily.[vi] Yet July’s two-year retail sales growth rate, 7.3%, is right in line with retail sales’ typical year-over-year growth in 2019.[vii] So we have a hard time seeing this slowdown as anything other than a return to normal.

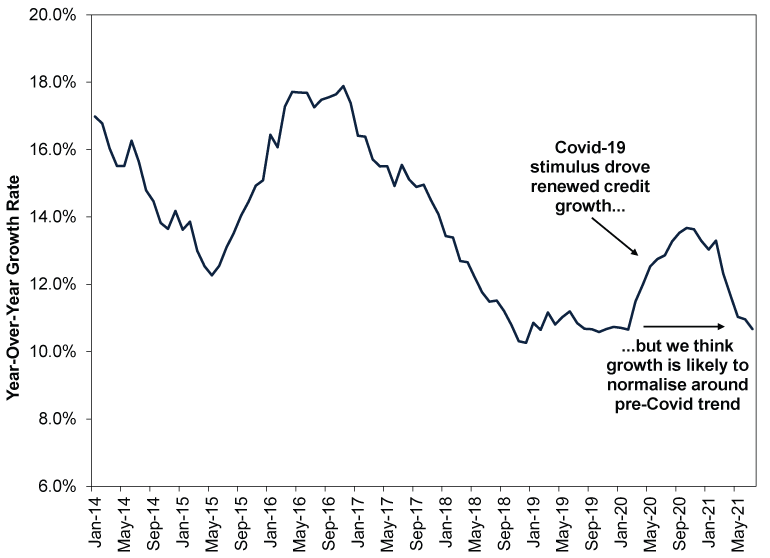

Yes, normal. Slowing economic growth rates have been the norm in China for years now, which we think is a logical consequence of the country’s shift away from fast, factory-led growth.[viii] It is also generally impossible to maintain torrid percentage growth rates as the economic base grows—just basic math. China’s normal also includes financial regulators’ long-running effort to tame excesses in the private lending world, which our research shows has a knock-on impact on growth. Last year’s small credit boom appeared to be a temporary suspension of this effort as officials sought to shore up the economy during and after the first COVID lockdowns. Therefore, we think slowing credit was to be expected after the economy stabilised, and that is indeed what we have seen since last autumn. July’s credit growth rates were in line with the pre-COVID trend, which we think is likely a good indication that some stabilisation is in the offing. (Exhibit 1) Note, too, that the government’s official policy guidance is now more neutral to supportive and focused on the apparent divergence between consumption and heavy industry. Whilst we don’t think that would be meaningful in free-market economies, in a command and control system like China’s, our research indicates it is frequently a decent harbinger of things to come. Therefore, it wouldn’t surprise us if fiscal and monetary policy also returned to normal: targeted support where needed to help services companies grow at a decent clip.

Exhibit 1: Total Social Financing

Source: FactSet, as of 13/8/2021. Year-over-year percent change in Chinese total social financing (a measure of total credit in the economy), January 2014 – July 2021.

If forced to guess, we would venture that the reason China’s data generated so many dour headlines is that sentiment is already in the pits due to the ongoing regulatory concerns surrounding large Chinese Internet firms whose shares are listed on exchanges outside China. When Event A causes sentiment to take a major hit, however overwrought, we have found it is quite normal for people to go fishing for reasons B, C and D to be worried. In our view, this is all an indication that sentiment toward China has fallen too far, too fast. China jitters look to us like a big brick remaining in this bull market’s proverbial wall of worry, not reason to be pessimistic on China or global equity markets today.

[i] Source: FactSet, as of 16/8/2021.

[ii] “Millions Are Again Under Lockdown in China Because of the Delta Variant,” Jane Li, Quartz, 4/8/2021.

[iii] Source: IHS Markit, as of 19/8/2021.

[iv] See Note i.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Source: National Statistics Bureau of China, as of 16/8/2021.

[vii] Source: National Statistics Bureau of China and FactSet, as of 16/8/2021.

[viii] Ibid.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights.

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

You Imagine Your Future. We Help You Get There.

Are you ready to start your journey to a better financial future?

Markets Are Always Changing—What Can You Do About It?

Get tips for enhancing your strategy, advice for buying and selling and see where we think the market is headed next.