Personal Wealth Management / Market Analysis

Your Friday International Economic Data Roundup

Here are some stats that caught our eye this week.

The world’s economic calendar was light on UK data this week, but happily for people who like digging into numbers, the rest of the world released a flurry of fun stats. In our view, economic data are generally backward-looking and don’t predict equity returns. Economic statistics report what happened in a previous month, quarter or year, whilst our research shows stocks generally price in what investors collectively expect to happen over the next 3 – 30 months. But we did find some nuggets of global interest, so let us share.

America’s record-high trade deficit is not the real story.

The US imported $80.9 billion worth of goods and services more than it exported in September, prompting the usually flurry of financial commentators hyping the record-high deficit.[i] In our view, the trade gap (exports minus imports) is a largely meaningless statistic with no bearing on a country’s economic health. Our research shows a deficit (imports exceeding exports) isn’t inherently negative, and a surplus (exports exceeding imports) isn’t automatically a sign of strength. After all, imports generally represent domestic demand, and because of the way international commerce works, a surplus of inbound investment inflows offsets a trade deficit. We think the trade gap is nothing more than an accounting factoid.

But the stats underlying America’s trade gap offer a pretty good snapshot of how the global logistics logjam works, in our view—and illustrates why hundreds of shipping containers are presently stacked in a field outside the Felixstowe port.[ii] US exports of goods fell -4.7% m/m, the biggest drop since last year’s lockdowns, whilst goods imports rose 0.8%.[iii] The mismatch seemingly stems not from plunging US factory output, which dropped only -0.8% in September, but from a lack of shipping containers.[iv] Or more specifically, a lack of readily available empty containers. The actual containers are everywhere, stacked a mile high at ports, in empty lots surrounding ports and at inland freight hubs—much like the container mountain by Felixstowe.[v] But there aren’t enough lorry chassis and hauliers to get them to warehouses for unloading. Nor are there enough warehouse workers to do said unloading. Or enough chassis and hauliers to then take the empty containers to the exporters who are desperate to fill them.[vi] Adding insult to injury, countless containers have made the return trip to Asia empty so they can swiftly ferry more goods back to America.[vii] Reloading them first would take too much time, potentially exacerbating US supermarket shortages.

In our view, the upshot of this is that, despite the scores of ships idling by major US ports, many are still docking and unloading, keeping shortages milder than they might otherwise be. From that standpoint, we think the 0.8% rise in goods imports is good news. But it does appear the logistics problems are hitting US exporters disproportionately, which is not so good. On the bright side though, most analysts we follow think this is likely to even out early next year, as shipping traffic slows after the holidays and rising wages entice more hauliers into the industry. In our view, this should eventually unleash the backlog of pent-up exports and prevent all those stacked containers from becoming permanent art installations.

Seriously, America’s huge productivity drop is good news.

Yes, really. We know productivity’s -5.0% annualised drop in Q3 is the biggest since 1981, and we know it doesn’t sound good.[viii] (The annualised rate is the rate at which productivity would fall over an entire year if the quarter-on-quarter rate of decline persisted sequentially all year.) Some commentators we follow say it points to inflation getting worse from here. But we interpret the data differently.

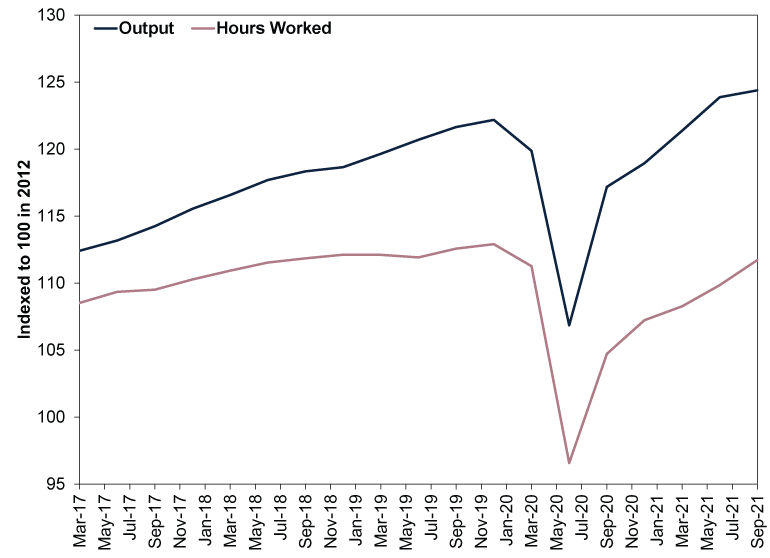

America’s official productivity measure is non-farm output divided by hours of labour. Both sides of that fraction have suffered big disruptions from lockdowns, with output recovering faster than hours worked. (Exhibit 1) This measure of output, which derives from GDP (gross domestic product, a government-produced measure of economic activity), hit a record high last quarter and passed its pre-lockdown peak in Q2. Hours worked is still a mite below its prior high. But it did catch up quite a bit in Q3, rising 7.0% annualised—in our view, a good sign that businesses are starting to overcome the labour shortage.[ix]

Exhibit 1: Productivity Deconstructed

Source: FactSet, as of 4/11/2021. Output and Hours Worked, Q1 2017 – Q3 2012. Indexed to 100 in 2012.

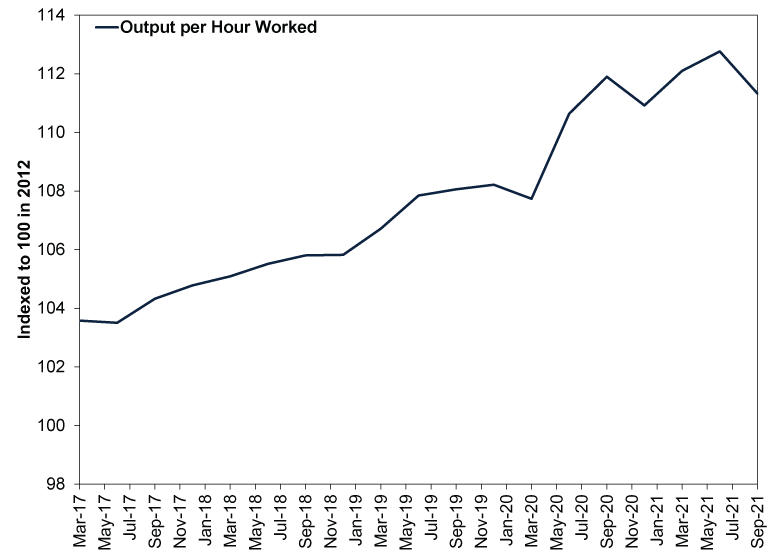

Also lost in the shuffle is the simple fact that productivity isn’t in the doldrums. The level of output per hour worked is actually at its fourth-highest reading on record, thanks to huge efficiency gains companies have made since the pandemic began. In our view, Q3’s drop simply reflects companies’ exhausting their ability to do more with less. The last couple of years are basically an outsized version of what our research shows is productivity’s usual path surrounding a recession.

Exhibit 2: The US Is Still Pretty Darned Productive

Source: FactSet, as of 4/11/2021. Output per Hour Worked, Q1 2017 – Q3 2021. Indexed to 100 in 2012.

Actually, German factory orders weren’t weak.

“Lockdown skew” also sums up our take on German factory orders, which eked out a 1.3% m/m rise in September after August’s -8.8% drop.[x] Several commentators we follow described the small rebound as feeble, implying Germany’s industrial sector is being severely hobbled by the aforementioned supply chain problems. Yet here, too, we think it is necessary to look further back in time to put the most recent results in context. As Exhibit 3 shows, German factory orders took a severe hit during last year’s lockdowns, driving big catch-up growth when the country reopened—which happened in fits and starts through summer 2021. Much of Europe also reopened this summer, which we think explains the big boom in July orders and subsequent drop-off in August. Yet even with orders remaining below that peak, they remain far ahead of orders in the years before the pandemic—and about in line with demand during Germany’s 2016 factory boomlet.

Exhibit 3: September German Factory Orders in Context

Source: FactSet, as of 4/11/2021. German Industrial Orders, real and seasonally adjusted, November 2001 – September 2021.

Now, high orders may not predict big output growth in the immediate future, as some factories are short on parts and labour. IHS Markit’s latest purchasing managers’ indexes show supplier delivery times remain strained and order backlogs are piling up. But as we have written before, supply issues are likely to prove short-lived. We do think they are a headwind, but they don’t signal creeping economic weakness the way a demand dearth would. And based on factory orders, demand just doesn’t seem to be a problem today, in our view.

[i] Source: FactSet, as of 4/11/2021.

[ii] “Shipping Container Mountain Created in Felixstowe Field Amid Haulier Shortage,” Staff, Hellenic Shipping News Worldwide, 5/11/2021.

[iii] See Note i.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] “Empty Shipping Containers Pile Up in LA While China Has Shortage,” Tori Richards, The Washington Examiner, 25/10/2021. Accessed via Yahoo!.

[vi] “Shipping Is Broken. Here’s How to Fix It.” Revecca Heilweil, Recode, 5/11/2021.

[vii] “This Is Why Almost Half of Cargo Ships Are Sailing Around Empty,” Myrto Kalouptsidi, MarketWatch, 16/6/2021. Accessed via MSN.

[viii] See Note i.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] Ibid.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights.

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

You Imagine Your Future. We Help You Get There.

Are you ready to start your journey to a better financial future?

Markets Are Always Changing—What Can You Do About It?

Get tips for enhancing your strategy, advice for buying and selling and see where we think the market is headed next.