Personal Wealth Management / Market Analysis

About the Eurozone’s ‘Record’ Inflation Surge

As in the US, we think one-off factors deserve the blame.

Record-high inflation. Biggest-ever jump. Those are two common phrases financial commentators we follow used to describe the eurozone’s November inflation rate, never mind the fact that the eurozone itself is scarcely more than 20 years old. Records come easy in young datasets, and this latest one doesn’t mean a repeat of the 1970s’ inflation spiral is at hand, in our view. Rather, we think a quick look at the limited data available in the preliminary release for the eurozone and member-states shows that—as in the US—prices are up on the collision of three temporary factors: supply shortages, calculation quirks called base effects and energy prices. That people think otherwise suggests to us that there is a lot of room for stocks to climb the proverbial wall of worry as inflation chatter gradually fades.

It is true that eurozone inflation, which hit 4.9% y/y, is relatively high and up sharply from October’s 4.1%.[i] But a lot of that comes from energy prices, which rose an astronomical 27.4% y/y and 2.9% m/m.[ii] Excluding energy, food, alcohol and tobacco (the eurozone’s measure of core inflation, which typically excludes volatile categories), prices rose 2.6% y/y and just 0.1% m/m.[iii] Non-energy industrial goods rose 0.4% m/m, bringing their year-over-year increase to 2.4% as supply shortages continued, but services prices continued easing with a -0.2% m/m drop—in our view, a sign that reopening from lockdowns has largely run its course as an inflation driver.[iv]

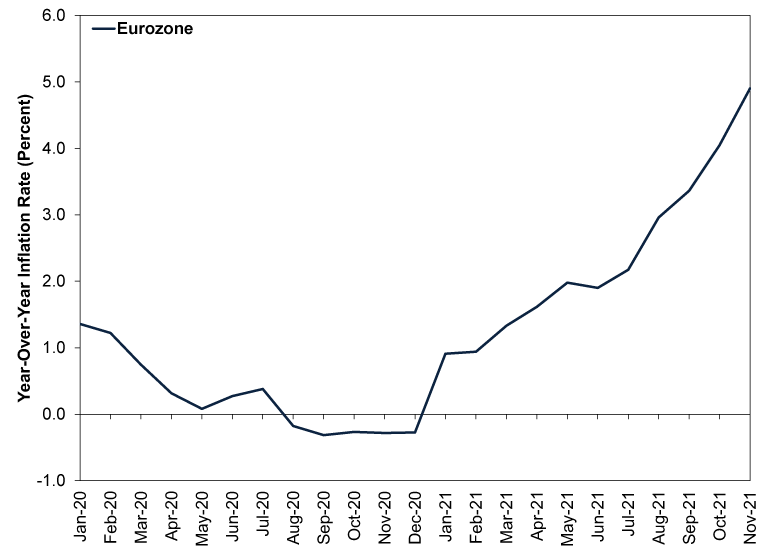

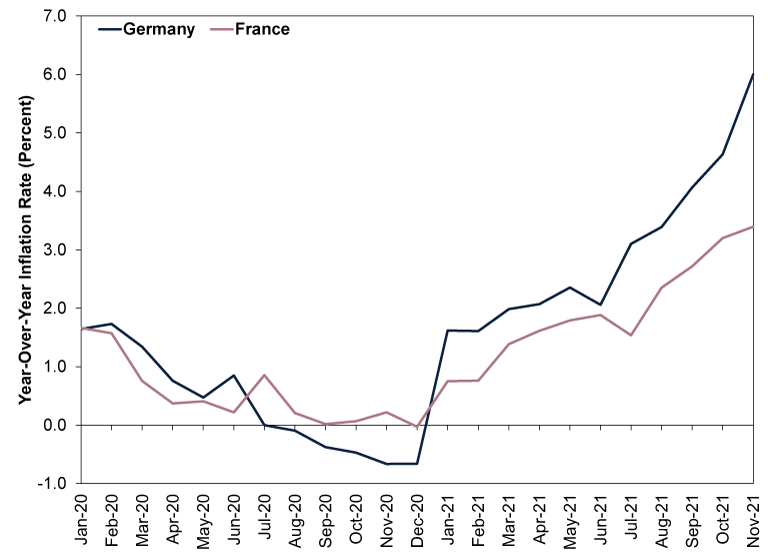

But price trends from last year continue adding skew—a mathematical phenomenon called the base effect. In the year-over-year inflation rate calculation, the denominator is prices a year ago. As Exhibit 1 shows, the eurozone was still in deflation a year ago, lowering that denominator and mathematically skewing the inflation rate higher. We think the impact is even clearer when you look at Germany and France. German inflation jumped to 6.0% y/y in November, the fastest since reunification of East and West Germany.[v] But French inflation barely inched higher, from 3.2% y/y in October to 3.4%.[vi] This wasn’t because France has stolen Germany’s traditional reputation for price stability, but because Germany experienced deflation in 2020’s second half after the government temporarily slashed its value-added tax (VAT) in the name of COVID relief. France, which didn’t cut VAT, didn’t have deflation last year. That means its year-over-year calculation base is higher than Germany’s, subjecting today’s inflation rate to less artificial upward skew.

Exhibit 1: Eurozone’s Inflation “Liftoff” Builds on Low Base

Source: FactSet, as of 30/11/2021. Eurozone Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP), January 2020 – November 2021. HICP is a government-produced measure of goods and services prices across the broad economy.

Exhibit 2: France and Germany Illustrate the Base Effect

Source: FactSet, as of 30/11/2021. Germany and France HICP, January 2020 – November 2021.

Not that the base effect alone is sufficient reason to dismiss higher prices—it isn’t. Households have had to swallow higher costs, especially on the energy front. Yet big short-term price increases aren’t synonymous with lasting inflation. For inflation to stay high for any meaningful timeframe, simple maths dictate that energy and other prices would have to keep rising at a fast clip from here. Right now, we don’t see reason to think that is likely. As we have covered numerous times in this space, there are many indications that the supply chain crunch is starting to ease. Same goes for energy prices, as oil production ramps up globally and European utilities adjust in the wake of the natural gas shortage.[vii] That doesn’t mean prices will plunge from here, but slowing inflation doesn’t require that.

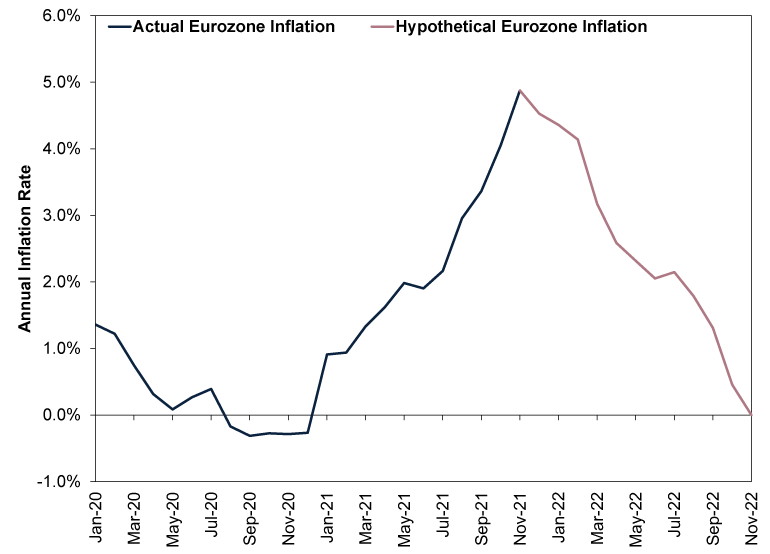

Consider: As Exhibit 3’s hypothetical illustration shows, if prices stay at November’s level for the next year, the inflation rate will slow as the base rises. That is an unlikely scenario, of course, but we think it illustrates the concept of a one-time price increase working its way in and out of the inflation rate.

Exhibit 3: Transitory Inflation, Version 1

Source: FactSet and Maths, as of 30/11/2021. Eurozone HICP, January 2020 – November 2021; presumes a 0.0% m/m inflation rate from December 2021 – November 2022.

Even in a more realistic hypothetical scenario of prices rising at 0.3% m/m, which is the US’s long-term average, the year-over-year inflation rate would ease.[viii] (Exhibit 4) Milder price increases off a higher base is the definition of transitory inflation, to use a word monetary policymakers frequently use.

Exhibit 4: Transitory Inflation, Version 2

Source: FactSet and Maths, as of 30/11/2021. Eurozone HICP, January 2020 – November 2021; presumes a 0.3% m/m inflation rate from December 2021 – November 2022.

As for the inevitable chatter about European Central Bank (ECB) policy, which accompanied the inflation data, we think it remains off base. One, supply shortages and energy prices are outside monetary policymakers’ control—ECB President Christine Lagarde and her colleagues can’t clear backlogs at ports or drill for oil. Two, even if inflation were coming from too much money rather than chasing too few goods, we don’t think ending quantitative easing asset purchases would fix it. When the ECB and other monetary policy institutions buy long-term assets, they tamp down long-term interest rates, which flattens the yield curve (a graphical representation of a single issuer’s interest rates across a range of maturities). Banks borrow at short-term rates and lend at long-term rates, which we think makes the yield curve a reference for their potential profit margins on new loans. When it flattens, potential profits typically flatten, which our research shows saps lending. When the yield curve steepens and potential profits widen, we find that banks tend to lend more, which speeds money supply growth. If the ECB were to stop quantitative easing tomorrow, we think the yield curve would probably steepen a bit. Our research shows that is inflationary, not deflationary.

In short, give it time. Today’s price pressures likely won’t last forever. When they ease, we think there is a world of positive surprise in store for those preoccupied with financial commentators’ warnings about inflation today. Inflation isn’t inherently a stock market risk, in our view, but inflation chatter seems to be holding down expectations now. Our research shows stocks move on the gap between reality and expectations, and as inflation fears gradually fade, we think it should help stocks climb up the wall of worry.

[i] Source: Eurostat, as of 30/11/2021.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Source: FactSet and US Energy Information Administration, as of 30/11/2021. Statement is based on the decline in Dutch TTF natural gas prices and US oil production.

[viii] Source: BLS, as of 30/11/2021.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights.

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

You Imagine Your Future. We Help You Get There.

Are you ready to start your journey to a better financial future?

Markets Are Always Changing—What Can You Do About It?

Get tips for enhancing your strategy, advice for buying and selling and see where we think the market is headed next.