Personal Wealth Management / Market Analysis

Breaking (Up) Bad (Tech)?

Politicians are increasingly making noise about breaking up big Tech. Here we put the chatter in perspective.

Editors’ Note: MarketMinder does not recommend individual securities. The below merely represent a broader theme we wish to highlight. Likewise, we favor no party nor any politician and assess politics solely for their potential market impact.

Competition should breed excellence. In a crowded early primary campaign season ahead of 2020, the competition for American voters’ attention is already spawning some eye-catching proposals. Many target big Tech companies—ranging from tax plans to shake-ups and breakups. While the chatter increases regulatory risk for the sector some, we see material legislation as unlikely. Don’t let it scare you away from Tech.

Perhaps the most-discussed plan belongs to Massachusetts Senator (and presidential candidate) Elizabeth Warren. Warren recently proposed dismantling big Tech and Tech-like giants in the name of fairness and consumer protection. As the Senator sees it, “Today’s big tech companies have too much power — too much power over our economy, our society, and our democracy. They’ve bulldozed competition, used our private information for profit, and tilted the playing field against everyone else. And in the process, they have hurt small businesses and stifled innovation.” Yikes! We had no idea our two-day shipping and family photo sharing caused such despair.

Warren isn’t alone. Just last month, the Federal Trade Commission created a competition task force to review pending and completed Tech M&A. The task force, an offshoot of the Bureau of Competition, focuses solely on Tech firms and seeks to quell “anti-competitive conduct.” Bureau of Competition head Bruce Hoffman stated the task force would look to unwind “problematic mergers” by breaking up or requiring firms to spin off previous acquisitions. Republican Senator (and 2016 presidential candidate) Ted Cruz similarly argues big Tech wields too much power.

But Warren has shared the most details, at least thus far. Her plan would designate an “online marketplace, an exchange, or a platform for connecting third parties” as a “platform utility.” Such firms with more than $25 billion in annual revenue would have to split this function from other business units offering proprietary products or services. Consider one Tech-like giant that rhymes with Shlamazon. It wouldn’t be able to offer its own products via its marketplace, for fear it wouldn’t treat third parties fairly. While her plan wouldn’t require firms with less than $25 billion in annual revenue to formally separate, they would have to comply with the same tough regulatory requirements as their larger counterparts—operating internal divisions as if they were independent. She also stated Tech M&A would get more scrutiny, claiming social media acquisitions amount to anti-competitive behavior.

We have to give some credit to a candidate willing to put some semblance of detail into a proposal—a rarity this early in a campaign. However, because it is so early, there isn’t much point in dissecting all the plan’s components. It is bound to morph in the future, if it even gets off the ground (a big IF). Further, candidates largely design such plans to garner attention in a crowded primary. Better, in our view, to wait. Let the election process narrow the field and reduce the associated uncertainty before zeroing in on potential policies.

Yet the issue of what to do about big firms may linger, so looking at the history from an investor’s standpoint seems worthwhile. As Warren put it, “America has a long tradition of breaking up companies when they have become too big and dominant — even if they are generally providing good service at a reasonable price. A century ago, in the Gilded Age, waves of mergers led to the creation of some of the biggest companies in American history — from Standard Oil and JPMorgan to the railroads and AT&T.” (Editors’ note: The Gilded Age actually ended in the late 1890s, but whatever.)

Most of those breakups took place before reliable stock market data exist. AT&T is the exception. AT&T, Alexander Graham Bell’s legacy, dominated the telephone market for most of the 20th century, earning the nickname “Ma Bell.” At the time, the company and its subsidiaries were the only providers of telephone services and equipment in much of America, giving them nearly complete industry control. This led lawmakers to consider action to inject more competition. They sought to prevent companies from abusing their power by charging higher prices, offering worse quality, reducing innovation and favoring some customers over others. Instead of nationalizing these industries—as other countries did—Republican and Democratic reformers advanced antitrust laws. In 1974, the Justice Department filed suit against AT&T, seeking to break it up. After eight long years in court, AT&T finally agreed to settle the suit—and split up—on January 8, 1982. This forced AT&T to break up into eight smaller companies by January 1, 1984 known as “the Baby Bells.”

AT&T had trouble finding its feet after the split while the Baby Bells outperformed their "Ma." Looking to grab a piece of AT&T's market, long-distance carriers such as Sprint and MCI emerged as AT&T's main competitors. Price wars between these companies cut into AT&T’s profits. Meanwhile, SBC, which began as the Baby Bell named Southwestern Bell, expanded its services to include data, video and voice. By doing so, SBC went from being the smallest Baby Bell to the biggest. Eventually, the government loosened telecommunications restrictions and the Baby Bells began to merge. Over time AT&T has slowly reconstituted itself as the massive duopoly of the modern AT&T and Verizon.

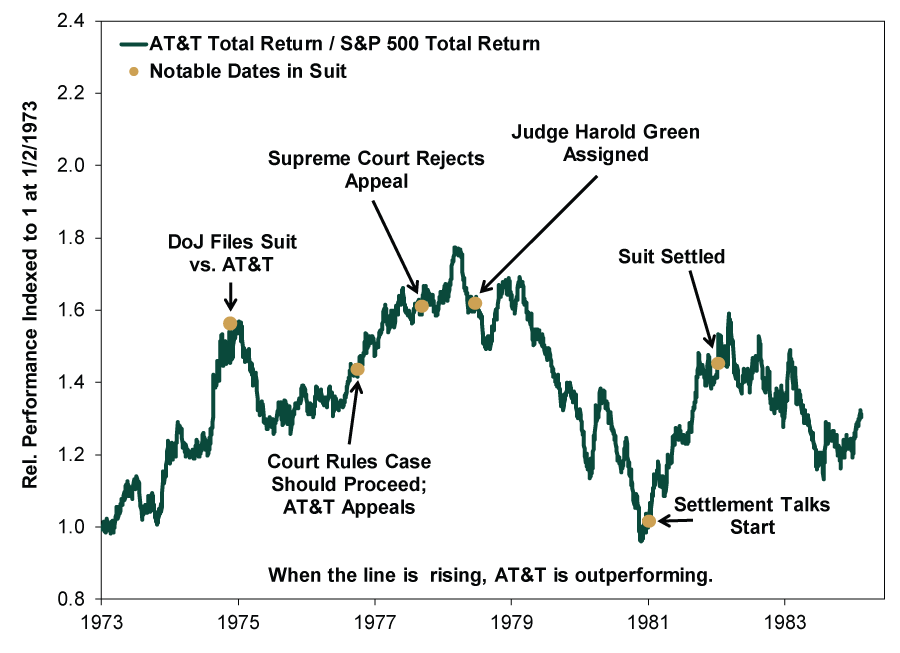

From a stock perspective, the impact of the trial and eventual split was mixed. AT&T slightly underperformed the S&P 500 during the eight-year court case, annualizing a 12.3% return against 13.5% for the S&P 500.[i] There were points of outperformance as the breakup developed, but we think major events in the legal case seem like inflection points—perhaps most notably the sharp underperformance between 1978’s court proceedings opening and 1981, when news of a potential settlement began emerging. (Exhibit 1)

Exhibit 1: AT&T vs. the S&P 500 During Breakup Proceedings

Source: Global Financial Data, Inc. and Datastream by Refinitiv, as of 4/24/2019. AT&T Corp. total return divided by S&P 500 total return, 1/2/1973 – 2/15/1984. Event source: “The 7-Year Chronology of the Suit Against Bell,” Staff, Associated Press, 1/9/1982.

After the split, AT&T shareholders made out a bit better. Investors owning AT&T prior to the breakup and holding throughout the next 12 years ultimately owned shares in 10 different companies and enjoyed 16% annualized returns.[ii] Of course, we don’t know what their return would have been without a breakup. However, it isn’t bad compared to the S&P 500’s 14.5% annualized over the same period.[iii]

Perhaps that comparison holds if America advances with efforts to split up big Tech. Perhaps not—after all, this is only one example–far from a robust data set. Moreover, if the efforts applied to multiple firms, it isn’t a stretch to think uncertainty could spread, weighing on stocks. That is especially true of Tech and Tech-like firms, which command a large share of US and global market capitalization.

But still, a breakup looks unlikely to us. First, political gridlock in Washington complicates passing any material legislation. This is a good thing and the primary reason why sweeping Tech legislation seems unlikely to us. Intraparty gridlock on both sides of the aisle makes it even more challenging. Many Tech hubs (e.g., Seattle, San Francisco) are Democratic strongholds that likely oppose heavy-handed regulation on Tech. Second, if consumer behavior and attitudes are any indication, the general voting public doesn’t see big Tech as so problematic. A recent NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll found 68% of respondents believe the government shouldn’t break up big Tech firms, preferring allowing the free market to operate.[iv] While the same poll showed many are concerned with personal data security, it doesn’t seem many Americans think they are financially harmed by the often free or near-free services many big Tech firms provide us. Given this, it is hard to imagine presidential hopefuls spending precious political capital on a topic unlikely to evoke emotional responses from potential voters. Finally, as Fisher Investments’ founder and Executive Chairman Ken Fisher recently wrote, governments seem happiest to nickel-and-dime big firms through tax-like fines. Can’t do that with small firms.

So what will police big Tech if the government doesn’t come in with new, sweeping laws? The poll hints at it: capitalism. Today’s Tech giants forged their own paths by creating goods and services that didn’t exist or making existing ones even better. Actually, many of them dethroned widely perceived monopolies in IBM and Microsoft to get there. In our view, this value creation should be rewarded, not punished. If a business isn’t offering a compelling service or product at a reasonable price, it should be consumers—not bureaucrats—who determine the firm’s survival.

Investors should be overjoyed consumers—not the government—rewarded big Tech with their sizeable market share. We think this process will continue over time, benefiting consumers, shareholders and our economy—so long as we let it.[i] Source: Global Financial Data, Inc. and Datastream by Refinitiv, as of 4/24/2019. AT&T Corp. total return (reinvested dividends) and S&P 500 total return.

[ii] “AT&T Rewards Steady Investors, Shares Held Since Breakup Have Outperformed Market, Knight-Ridder, May 25, 1996. https://www.spokesman.com/stories/1996/may/25/att-rewards-steady-investors-shares-held-since/

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Source: NBC News/Wall Street Journal, as of 4/24/2019. March 2019 survey of 1000 adults conducted over March 23 - 27, 2019. https://www.wsj.com/public/resources/documents/19093NBCWSJMarch2019Poll-final.pdf?mod=article_inline

If you would like to contact the editors responsible for this article, please message MarketMinder directly.

*The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Fisher Investments editorial staff.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

You Imagine Your Future. We Help You Get There.

Are you ready to start your journey to a better financial future?

Where Might the Market Go Next?

Confidently tackle the market’s ups and downs with independent research and analysis that tells you where we think stocks are headed—and why.