Personal Wealth Management / Economics

The BoJ Tries Even More of the Same, Expects Different Outcome

Japan’s yield curve really wants to steepen, but policymakers won’t let it.

Amid all the flurry of central bank activity in recent weeks, one bank has been relatively absent from headlines … until now. Yes, our old friends at the Bank of Japan (BoJ) are back at their creative monetary policy, this time buying up “unlimited” quantities of Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs) in order to force 10-year yields to stay between 0% and 0.25%. While you might think their success at holding this interest rate peg, known as “yield curve control” (YCC), is earning them a gold star, it is also contributing to a sharp slide in the yen as money flows toward higher-yielding assets. That presents a clear headwind for a nation that imports most of its energy, leading people to suspect the BoJ will have to raise its 10-year yield target by half a percentage point at least. If you have ever wondered why we say central banks are rate followers more than rate setters, this is why.

The BoJ, which invented quantitative easing (QE) over 20 years ago, started targeting 10-year yields last decade in an effort to keep the yield curve ever-so-slightly positively sloped at a time when markets were pulling long rates globally into negative territory. At the time, it functioned as a stealth tapering of QE. These days, the opposite is happening. Long rates across the developed world have shot up, and 10-year JGB yields are trying really, really hard to join them. That shouldn’t shock: Long rates globally tend to be highly correlated.

Hence, in order to keep them below 0.25%, the BoJ has conducted unlimited purchases since Monday. Thursday, the bank announced it would up its purchases for the next three months from a target of ¥1.7 trillion per month to ¥2.0 trillion.

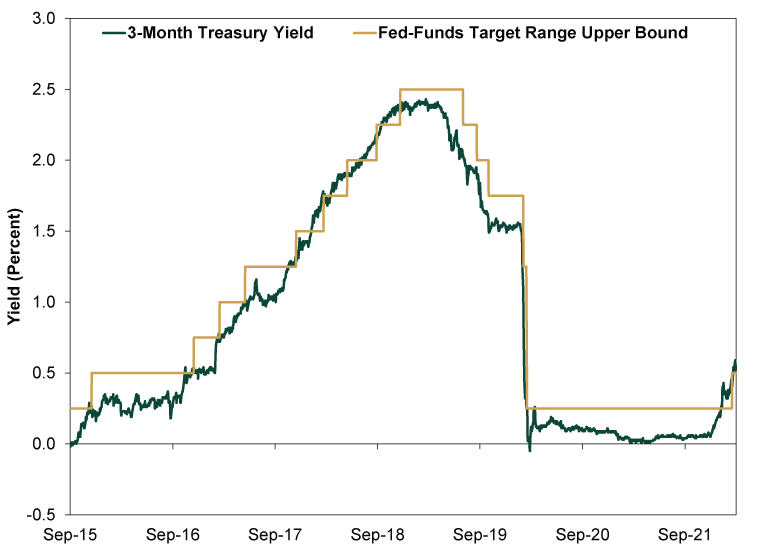

Whenever the BoJ decides to raise its yield target, we think it will be a mistake to say it is “raising” long-term rates. Rather, it will finally allow long rates to rise closer to where they would naturally be without a peg. That is, the bank will follow the market’s marching orders. It is the long-term rate equivalent of the Fed not raising its benchmark short-term interest rate until after market-set short rates like the 3-month Treasury yield have risen, which is the norm in recent years.

Exhibit 1: The Fed Follows the Market

Source: FactSet, as of 3/31/2022. US 3-Month Treasury Yield (Constant Maturity) and Fed-Funds Target Range Upper Bound, 9/30/2015 – 3/30/2022.

The cruel twist in all of this is that if the BoJ would listen to the market and let long-term yields rise, it would probably help assuage many of the central bank’s long-running problems. Japan’s primary headwind since the Nikkei bubble burst is lackluster domestic demand. The BoJ remains convinced low long-term rates are the answer, falling for the old myth that because low rates stimulate demand for borrowing, they must be stimulus. But that hasn’t worked out well, because in Japan, this meant engineering a flat yield curve. As you are probably tired of hearing us say if you have followed MarketMinder for any length of time, this is the opposite of stimulus. Banks borrow at short rates and lend at long rates, making the spread between them a rough proxy for the net interest margin on new loans. A flat curve means flat potential profits, which discourages lending to all but the most creditworthy borrowers. Said differently, low rates may boost loan demand, but they have the opposite effect on supply, keeping loan growth—and domestic demand—weaker.

Letting long rates rise would steepen Japan’s yield curve, bringing some welcome relief on multiple fronts. More capital would flow through the economy, boosting domestically focused businesses that can’t simply bank easy profits from converting export revenues back to yen when the currency is weak. Faster money supply growth would trample the deflationary forces that the BoJ has long battled, likely helping lift prices closer to the BoJ’s target. That would be a welcome change, considering inflation has reached the target thanks only to high energy prices and sales tax hikes over the past decade. That isn’t the sort of modest inflation that is a healthy side effect of economic growth.

But alas, BoJ policymakers keep trying the same failed experiment, apparently leaning on a monetary strategy that could be summed up as, “the beatings will continue until morale improves.” Now, that is fine for large export-heavy Japanese multinationals, but Japanese stocks that rely on domestic demand will probably continue to face tough sledding until the BoJ comes to its senses, realizes two decades of economic history is worth learning from, and starts heeding the market’s signals.

If you would like to contact the editors responsible for this article, please message MarketMinder directly.

*The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Fisher Investments editorial staff.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

You Imagine Your Future. We Help You Get There.

Are you ready to start your journey to a better financial future?

Where Might the Market Go Next?

Confidently tackle the market’s ups and downs with independent research and analysis that tells you where we think stocks are headed—and why.