Personal Wealth Management / Economics

Don’t Fret Low Productivity

Slow productivity growth is no reason for investors to worry.

What ails the US economy? No one can say exactly, but many arguments boil down to a lack of productivity growth. Many call it the great economic scourge of our time, consigning America (and maybe the world) to permanently low growth[i] and weak stock returns. In reality, however, productivity simply isn't predictive-not of stocks, economic growth or future productivity.

First, some background. Labor productivity is value-added output per hour. If you totaled all hours worked every year and then multiplied the result by productivity, you would get GDP. Or, flip it around: If you divided GDP by total hours worked, you get productivity. Higher productivity theoretically allows folks' incomes and living standards to rise without their working more hours, while weak productivity supposedly means stagnant wages, since companies would have to protect margins.

Adding up hours worked is relatively straightforward, but measuring output is fuzzier. Government statisticians simply limit themselves to tallying up the value of monetary transactions (i.e., sales and investment).[ii] The problem isn't so much with the concept of GDP itself-it does what it's supposed to do-but how it's (mis)used and (mis)interpreted. For example, it isn't a measure of well-being. It also excludes a lot of work, as non-market activity and non-transactional output like, um, MarketMinder articles, don't count, even if they make you happy. As a statistic, it is built for the industrial era, not the technology/services-driven economy.

Stocks Care About Profits, Not Productivity

In any case, stocks don't care about productivity or even the speed of economic growth. They care about profits-specifically, profits relative to expectations. Productivity says very little about the financial health of a firm or industry.

Productivity loosely measures the value workers add to the economy (per hour), not to corporate bottom lines. While productivity takes into account items like cost of goods sold and non-wage expenses when calculating value added from sales, it ignores wages and other costs like interest, rent and depreciation. So while it says a lot about the number of proverbial pies per hour being sold in the marketplace, it says nothing about how the value-added from those pies-over the cost of their ingredients-is split between the pie company's profits and its workers.

What matters to stocks is whether the economy is growing enough to keep corporate profitability stronger than expected. Neither productivity nor GDP can predict future economic growth, because they are backward-looking indicators and, in productivity's case, lagging. What just happened doesn't predict what will happen. And stocks care about what's going to happen, not what's already in the rear-view mirror. Moreover, productivity and GDP statistics incorporate non-corporate expenditures (think small businesses and private partnerships), which make them flawed measures for assessing public stocks, even if they were somehow predictive.

Low Productivity Not a Disaster

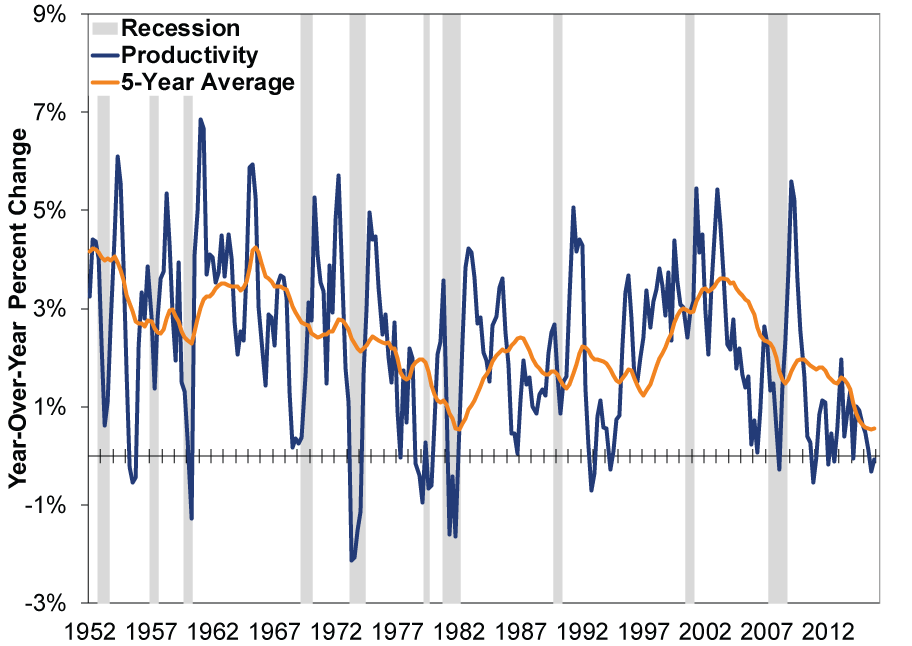

While productivity can swing wildly from quarter to quarter, average or "trend" productivity growth over the last five years is at its lowest level since 1982 (see Exhibit 1). Yet the economy has been chugging along ok; real GDP growth over last five years has averaged 2.1%. Could be better (it always can-perhaps why economists are noted to be such a dismal lot), but low productivity growth just isn't the terrible bugaboo it's made out to be.

Exhibit 1: O Productivity, Where Art Thou?

Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve, as of 11/18/2016.

What's more, profits are near record highs and moving higher. Payroll growth has been steadily improving. Business activity has been broadly expanding. Loan growth is swift. The Conference Board's Leading Economic Index signals more to come. All amid generationally low trend productivity growth. Word of America's demise is greatly exaggerated.

It Gets Better! (Eventually)

With all that said, there is room for improvement. The last time trend productivity growth was so low, it rebounded for the next two decades.[iii] That doesn't make a similar spike automatic, but it does reinforce the notion that weak productivity isn't a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The zeitgeist calls for politicians to do something about weak productivity, but we're wary of this-the law of unintended consequences is always ready to strike. Plus, demands to improve productivity growth presume that we know why it's low. So what's driving the productivity slowdown? According to some, forty somethings, apparently, because they're innately productive but falling as a percentage of the workforce. But barring forty somethings' innate "good balance of experience and creativity" and their demographic decline, the main hypotheses include:

- Technology is way overrated: The internet is just a bunch of timewasting free stuff[iv] subsidized by advertising (cat videos make us less productive) and creates measurement problems (making/watching cat videos should count as economic activity!);

- Academic arguments: insufficient aggregate demand and attendant lack of willpower from either fiscal or monetary authorities to do anything about it;

- Think tank arguments: not enough supply side structural reforms to unleash latent entrepreneurial mojo to bring about True Capitalism.

- Demographics, natch.

- Too much debt.

Or some combination thereof, since they aren't mutually exclusive. We aren't going to resolve this here (watching cat videos), but we sympathize with those who bemoan measurement mishaps and red tape. As John Cochrane recently put it: "Slow growth is not hard to diagnose or to cure. The U.S. economy suffers from complex, arbitrary and politicized regulation. The ridiculous tax system and badly structured social programs discourage work and investment." Now, perhaps that's a bit of an overstatement, but Obama's economic adviser Jason Furman,[v]Fed Vice Chair Stanley Fischer[vi] and The Donald himself all agree with the broader sentiment (to varying degrees). While we can see the point, all probably understate how competitive the US already is and overestimate the potential fruits of sweeping tax reform and deregulation, which aren't likely to sail through a divided Congress. Then, too, markets often dislike sweeping legislation, which creates winners and losers. There is no panacea.

We just don't know-either what works or which policies, if any, will ever see the light of day. What we can say is that markets-which are better gauges of the economic outlook than opinions-don't seem to mind terribly. As an old market mantra goes: "The best cure for high prices is high prices." The same can be said for low productivity. Over time, as markets do their thing and capital flows to its most productive uses, low productivity should take care of itself. Necessity is the mother of invention, after all.

People, and markets, adapt. To expect otherwise is to ignore history.[vii] Stocks, in the meantime, will probably keep ignoring productivity-however it's measured-and move higher over the foreseeable future as the overall economy expands and sentiment catches up with reality.

[i] And what if the US is actually doing well? If the malaise is so hard to pinpoint, it could just be psychosomatic. But for the sake of argument, there go I.

[ii] For the most part; the BEA has been dallying in 'hedonic' quality adjustments. Cf. The BLS' use of 'implicit prices', e.g. implied rent, when calculating almost a quarter of CPI.

[iii] This was when Reagan was in the middle of his first term, and many credit his economic policies for unleashing America's private sector. Whether that view is accurate or the feat is repeatable are both matters of great political debate. Expecting similar legislative feats this time around is probably fruitless, partly because President-elect Trump lacks a popular mandate and Reagan had far more low-hanging fruit (e.g., 70% marginal tax rates). But perhaps there are areas where Congress and the White House overlap that could bring incremental change.

[iv] Aka, consumer surplus.

[v] Here seen juggling. Also Matt Damon's college roommate, for what that's worth.

[vi] Footnote to footnote 13: "One related hypothesis, identified with Mancur Olson, is that, absent major shakeups of the institutional structure of the economy, the gradual accretion of the barnacles produced by the political process slows the vitality of the economy until eventually the public is willing to face the difficulties attending the structural reforms needed to restore that vitality."

[vii] And evolution.

If you would like to contact the editors responsible for this article, please message MarketMinder directly.

*The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Fisher Investments editorial staff.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

You Imagine Your Future. We Help You Get There.

Are you ready to start your journey to a better financial future?

Where Might the Market Go Next?

Confidently tackle the market’s ups and downs with independent research and analysis that tells you where we think stocks are headed—and why.