Personal Wealth Management / Market Analysis

The EU’s Transaction Tax Follies

The EU’s new Financial Transactions Tax is a beast, but will it see the light of day?

Yesterday, the European Commission sent the world a Valentine: A 39-page draft of the forthcoming Financial Tranactions Tax (FTT).

Don’t expect it to win them many dates.

For those who haven’t followed the FTT’s twisted saga, it began in 2011 when Germany, France and other eurozone states suggested taxing financial institutions’ transactions to make them pay “their fair share” for the costs of 2008’s bailouts. They initially sought to enact it EU-wide, but the UK (sensibly) vetoed it, and some gun-shy eurozone states prevented them from enacting it in the eurozone only. But they persevered, and last month, 11 eurozone nations won approval from EU finance ministers to adopt the tax under the EU’s “Enhanced Cooperation” measures, which allow some member states to trailblaze common legislation the broader union isn’t quite ready for.

Once they won approval, the real work started—namely, determining the tax’s scope and technicalities. The gang of 11—Belgium, Germany, Estonia, Greece, Spain, France, Italy, Austria, Portugal, Slovenia and Slovakia—outsourced this key task to the unelected bureaucrats at the European Commission (EC). Not surprisingly, the eurocrats managed to draft one of the ghastliest tax proposals of all time—and one that goes way beyond the scope of what finance ministers originally signed off on.

(Cue loud objections from London and elsewhere.)

When finance ministers rubber stamped the idea, they assumed the tax would only apply to transactions occurring in the participating member states, making it relatively easy to avoid and limiting the impact on their own financial services industries. They also assumed it would apply largely to banks’ proprietary trading, limiting its impact on savers, pensioners and retail investors (though, they fully expected banks to pass on the tax to consumers—one of many reasons it’s a dubious undertaking). Not all states thought it was a good idea—the UK and Czech Republic noted their objections and abstained from the final vote—but even the non-participating nations didn’t have much inventive to veto the tax. After all, if their neighbors want to make their financial sectors less competitive, they’d likely stand to benefit.

Unfortunately (and problematically, but I’ll get to that), the EC had something else in mind—their primary goal was preventing “avoidance and abuse.” And in doing so, they created a beast that will hurt pretty much anyone trading any financial instrument anywhere in the world.

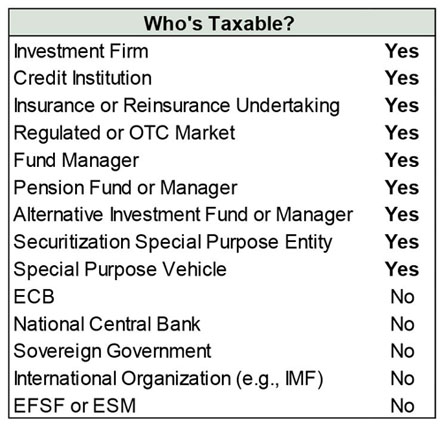

Here’s how: The tax won’t just apply to taxable entities transacting in the participating states or parties to trades that take place in these states—any financial instrument domiciled in a participating state will be subject. So, if a bank in the US sold a share of, say, Volkswagen to a bank in China, they’d have to pay up. And banks’ proprietary trades aren’t the only target—market making, prime brokerage activity, and any trades any financial institution conducts on behalf of any account, individual or institutional, are fair game. Ditto for trades conducted by any investment firm, pension fund, mutual fund or insurance firm (the ECB, sovereign governments and international organizations are suspiciously exempt), as shown in Exhibit 1.

Exhibit 1: Taxable Entities

Source: European Commission

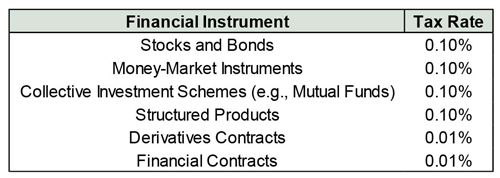

And, predictably, every financial instrument you can imagine is taxable—specifically, the purchase or sale of, transfer of, conclusion of derivatives contract of, exchange of, repurchase/reverse repurchase agreement for or borrowing/lending agreement for every financial instrument you can imagine. (Exhibit 2)

Exhibit 2: FTT at a Glance

Source: European Commission

The banks may be in the EC’s crosshairs, but investors of all stripes and sizes will get whacked—and despite the FTT’s Robin Hood aims, in practice, it’s a regressive tax on laypeople everywhere.

On the bright side, FTT should still be difficult to enact—objections will be strong. From here, the draft goes back to all member-states and the European Parliament for debate, and the participating 11 must vote unanimously to implement it. During the debates, expect the non-participants to wage war and beg Germany, France, Italy et al to realize the tax, if enacted, will slowly gut their financial systems and business environments. Not only does the tax discourage capital markets activity in the participating countries—and discourage banks, investment firms, fund managers and the like from operating in them—but it discourages businesses from issuing securities in them. If the tax takes hold, companies will likely cease issuing corporate bonds in these countries—they’ll register them outside the tax zone, and possibly move headquarters while they’re at it. Ditto for stocks—the London Stock Exchange, which just eased listing requirements, will look very attractive. Firms could also move to Ireland and issue shares there, where they’d be FTT-free and enjoy that (deliciously non-harmonized) 12.5% corporate tax rate.

The last thing these 11 states need is an exodus of business and capital markets activity—that goes double for Portugal, Greece, Spain and Italy, which desperately need to improve competitiveness. Despite the EC’s revenue estimates, it likely won’t help shore up their debt troubles—lost business and financial activity means lost growth, which likely means a net revenue loss. These countries need more business, not less.

In short, the EC’s press release may have been titled, “Taxing Financial Transactions – Making It Work,” but it clearly doesn’t.

Simple logic should dictate these nations will come to their senses and back off. But these are politicians and bureaucrats, so irrational behavior is a risk. What, then, if the FTT somehow goes live? Will we all have to pay our dues to Brussels?

Recent history suggests we won’t. Remember that carbon tax the EC tried to enact on every plane flying in EU airspace? Many countries—US, China and India included—refused to pay, the EC couldn’t do a darned thing about it, and the tax died. Foreign opposition could very well kill the FTT tax, too. Already, reports are emerging the concept as drafted is in violation of existing tax treaties between the US and France, which could quash FTT. So could the pending US-EU free trade talks, which will center on liberalizing services markets—including financial services. The US could easily make FTT a deal-breaker, likely forcing the EU to abandon it—and most members of the US government have already denounced FTT.

So here’s hoping FTT drowns in bureaucracy and international politicking, dying a painful death. Even if it doesn’t though, while it is a negative for participating states, it shouldn’t much hurt global growth or financial services—business and capital markets activity likely just flocks to friendlier shores, just as it always has. The tax would create winners and losers—all taxes do—but the world should keep chugging along.

If you would like to contact the editors responsible for this article, please message MarketMinder directly.

*The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Fisher Investments editorial staff.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

You Imagine Your Future. We Help You Get There.

Are you ready to start your journey to a better financial future?

Where Might the Market Go Next?

Confidently tackle the market’s ups and downs with independent research and analysis that tells you where we think stocks are headed—and why.