Personal Wealth Management / Market Analysis

Random Musings on Markets 2019: Musings on the Edge of Town

In which we bring you a collection of financial news oddities.

In this Friday’s not-every-Friday roundup of fun financial news-related stories, we bring you a blast from the startup past, our working theory on Libra, some lessons from Sir Paul McCartney, a debut musing on simple words from our own Jamie Silva and what craft beer can teach us about seltzer and bubbles generally. Please enjoy responsibly!

Back to the Future, Start-Up Style

Last weekend, The Wall Street Journal ran an interesting piece on the rise and fall of VisiCalc, an early spreadsheet software program that basically minted money in the very early 1980s. It was on top of the world in 1983. By 1984, it was dead.

The article tries to draw comparisons between then and now, arguing today’s Tech giants have basically turned themselves into permanent monopolies to avoid getting disrupted by competitors the way VisiCalc allegedly did. We didn’t find the argument terribly convincing, as it doesn’t account for how the incentives have changed for startups. Going public is much more of a hassle now than in the 1980s, making mergers an easier way for founders and early investors to cash out. It is a symbiotic transaction, not corporate predation.

But that is all beside the point. Most striking about this article? It kept referring to “VisiCalc’s publisher” without ever naming said company. We know the company’s name, and we didn’t even have to look it up. It was called VisiCorp. Elisabeth remembers toddling around its office once or twice as a wee kiddo. She remembers its sign being in someone’s garage, maybe even hers, and is pretty sure this is documented in an old family photo album.

Anyway, we highlight this to make a simple point: Tech has a high failure rate. A lot of blood, sweat and tears go into startups, but many don’t make it. History remembers the monster successes, making the sector and its startups look like surefire wins. That’s why folks flock to funds investing in late startups. (Exhibit A: Neil Woodford.) Maybe if history paid more attention to the failures—and actually bothered to report their names—investors would have a more measured view, stop looking for quick IPO riches and make better decisions.

A Working Theory on Libra

Last week, we mentioned Libra—the as-yet non-existent cryptocurrency affiliated with Facebook—in our discussion of Fed head Jerome Powell’s testimony to the House Financial Services Committee. Well, wouldn’t you know it, this week the Senate Banking Committee and House Financial Services Committee each had hearings exclusively on Libra. There may be more coming—starring Mark Zuckerberg! Set your DVR.

Anyway, there was a lot of outrage. Lots of folks telling Facebook execs they couldn’t just “move fast and break stuff” like in the Tech world.[i] Lots of worrying, generally. Ranking Member Rep. Patrick McHenry hilariously asked Facebook Executive David Marcus whether Libra was, “just a ploy to get Facebook’s Twitter mentions to go through the roof.”[ii] In a slow financial news week, Libra was—perhaps partly due to the hearings—hard to miss.

Yet we are quite confused by all the attention. We get why politicians and regulators would be interested. There are legitimate concerns regarding anti-money laundering and probably some data security concerns. They may be right to be concerned.[iii] Oh, and there is also the opportunity to flog Facebook publicly, which politicians might think would score points with voters. Cue the hearings.

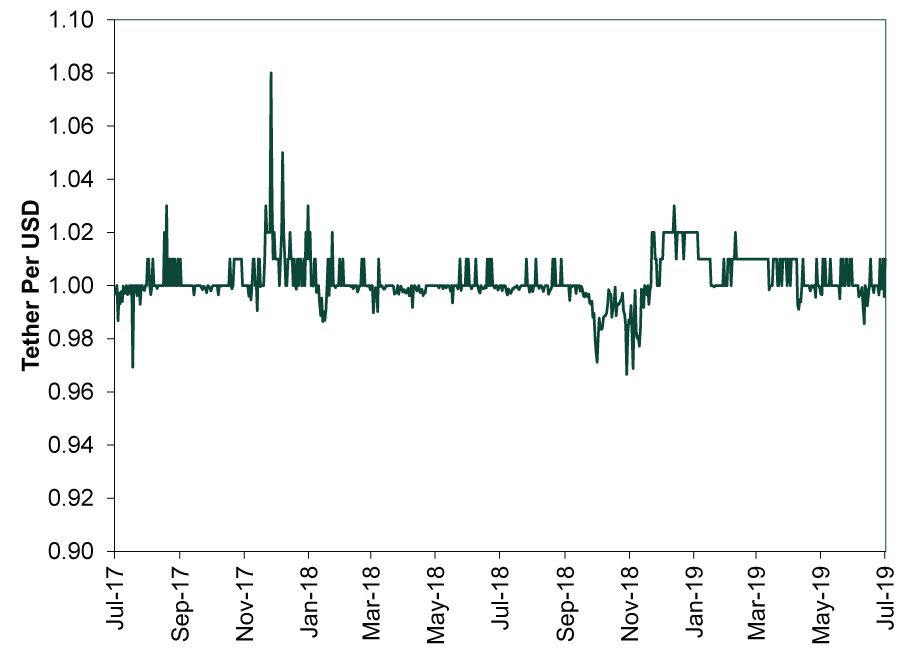

Our confusion is more on the end of the fascinated financial pundit or investor. Unless you own Facebook—and even then it may be a stretch—we just don’t see the interest. Libra differs pretty dramatically from bitcoin. With bitcoin, a primary reason it fails as a currency is its habitual ginormous price swings. Libra aims to fix this. It is what cryptopeople call a stablecoin. There already are such stablecoins, like Tether—a cryptocurrency pegged to the dollar. (The lack of congressional uproar over it hints at that “flog-Facebook-for-publicity” theory being a pretty accurate explanation for the hearings.) If Libra becomes a thing, it would be pegged to a currency or basket of currencies in order to limit price swings (up and down).

Said differently, if Libra becomes a thing and works as intended, there won’t be any “[Libra] Surges Past $10,000 for the First Time in a Year” headlines. No “Bitcoin Loses Almost a Third of Its Value as Libra Hype Fades.” There will be little movement at all! That is the point! Exhibit 1, which plots Tether’s swings over the last two years, illustrates this. Tether is thinly traded, too. If, as politicians seem to think is likely, Facebook uses its gargantuan subscriber base to popularize Libra, it would likely be far more liquid—and swing even less than Tether as a result.

Exhibit 1: Tether, a Libra Precursor, Is Pretty Dull

Source: CoinMarketCap.com, as of 7/17/2019.

Now, in our experience, the primary reason most investors paid one iota of attention to bitcoin was its tendency to boom and bust. Blockchain, the technical accounting system underlying bitcoin, may be novel and eventually a landmark technological change that rules the world, but it is also exceedingly boring.

Absent fluctuations, why would an investor be interested in Libra? We doubt headlines shrieking “Libra Still Worth Basically What It Was Yesterday” will garner many clicks. Probably even less investor attention. So our working theory, which may be totally wrong: The day folks lose interest in Libra will be the day it becomes a reality.

Simple Words About Complicated Things

Here at MarketMinder, conveying complicated financial concepts in simple, coherent language is one of our most challenging but important tasks. We strive to keep our commentaries jargon-free—or we define any unavoidable jargon. So we were excited to encounter a piece that attempts to “explain complex and interesting technical concepts in crypto[currency] as simply but thoroughly as possible using only the one thousand (ten hundred) most frequently used words in the English language.” This radical exercise in simplicity yielded many sentences like this one: “The person who made Bit Money had a great new idea to fix the problem of spending computer money more than once by having a group of people talk to one another about a great big book of computer money.” Hey, they are talking about a distributed ledger! A concept so complicated that this mumbled explanation makes about much sense as some thousand-word thinkpieces we have read. Cooooool.

With this as inspiration, here is an Explanation Using Only Very Basic Vocabulary of why a long-lasting, substantial global yield curve inversion[iv] typically isn’t great for the economy.[v]

Ahem:

When banks give money to people on the condition they give it back later plus extra (interest), they create new money—good for the economy! Banks get the money they need by raising it from other banks and people short term. But when far future interest rates[vi] are lower than soon interest rates, it costs more for banks to get money than they get paid by the people they lend money to. So they don’t give as much money to people who want it, and there is less money in the economy. This is bad because lots of companies need the new created money in order to grow and earn more money of their own.

Whew! That was exhausting, but still, a good exercise!

Life Lessons From Sir Paul

Paul McCartney just wrapped up a giant world tour, playing three-hour sets with the energy of someone half his age. Elisabeth went to his San Jose show, and somewhere between his John Lennon tribute and his George Harrison tribute, she started thinking about all the drama over the Lennon/McCartney publishing rights, Harrison’s legendary frustration at getting shut out, and the infamous McCartney/Michael Jackson falling out. And in what may or may not be the worst analogy of all time, we thought there might be some investing lessons.

For those who didn’t follow the decades-long drama, a series of bad deals and corporate battles left Lennon and McCartney with no ownership over the Beatles’ back catalogue. The rights belonged to a company, which they owned a small stake in until 1969, when they were shut out and bought out, causing them to miss decades of licensing fees. Any time a Beatles song was in a TV show, commercial or movie, someone else got the money. Suffice it to say, this income stream wasn’t accurately factored into their selling price.

When Sir Paul recorded a duet with the King of Pop in the early 80s, he shared this story, his regrets and a lesson: Own your publishing. Michael listened ... and won those Lennon/McCartney publishing rights when they were auctioned a short while later, paying a cool $47.5 million. That spelled the end of their acquaintance, and by the time Jackson died in 2009, the catalogue was worth $1 billion. Seven years later, his estate sold his remaining stake to Sony in a deal valuing the rights sat $1.5 billion. A year later, Sir Paul finally regained the copyright after settling a lawsuit against Sony. We suspect he was not compensated for missed revenue.

Lesson One: Opportunity cost is a thing. Not that Paul and John wanted to sell in 1969, but while the £3.5 million they got in the buyout was above market value, it wasn’t exactly an accurate reflection of the future income stream.

Lesson Two: Seemingly high prices can go higher. A lot higher. McCartney didn’t try to bid against Jackson in 1985, perhaps because the price seemed too steep. He had already moved on and invested in other artists’ publishing rights, which were valued in the tens of millions of dollars at the time. We figure if he knew his back catalogue would jump to $1.5 billion in 31 years, he would have decided differently.

Lesson Three: The Lennon/McCartney catalogue is the exception, not the rule. Some newfangled funds today give retail investors the chance to own a stake in classic rock artists’ publishing rights. They draw comparisons with the Lennon/McCartney saga, but only the Beatles were the Beatles. Just like you can’t buy any random Tech stock and expect Apple-like long-term returns.

Lesson Four: Go to all the gigs. All of them.

The Seltzer Bubble

We enjoyed The New York Times’ July 13 article featuring the wonderful title we stole for this musing documenting America’s increasing fascination with fizzy water of all types. Flavored. Home-produced. Independent, craft-created. Mass produced. Alcoholic. And, standing at the center of a fad Venn Diagram, CBD-infused fizzy water, which we are sure is the secret key to happiness and possibly the fountain of youth.[vii] Investment into the space is pouring in, with new products launching frequently.[viii]

The article explores the theory this is all getting carried away—a bubble, to use financial terminology. Which, maybe? But we also happen to think folks see far more froth than actually exists—and this may be another case. Look at craft beer, as we plan to around 6 PM tonight. According to Brewers Association data, in 2008 there were 1,521 craft brewers in America.[ix] In the last decade, this has gone parabolic, with America sporting 7,346 as of 2018.[x]

Now, since, say, 2014, craft brewing’s growth rate (in terms of net new breweries) has slowed. Further, there are some signs of oversaturation. Todd, who happens to reside in Portland, Oregon—an incredibly competitive craft brew marketplace—has witnessed several local mainstay breweries close in the last year, including Bridgeport Brewing—one of the original Portland craft brewers that opened in 1988. But still, nationally, craft brewing is growing, with 322 microbreweries opening last year versus 90 closures.[xi]

To bring this back to seltzer: Maybe there is room for yet more fizzy water beverages in Americans’ lives? Trends like this may be a sign of consumers’ tastes changing—or their perception of health benefits shifting. Those can have long-lasting impacts, rendering allegations of froth premature.

Enjoy your weekend!

[i] We dare say it would have turned this into a meaningless cliché, if it already weren’t one.

[ii] An unlikely theory, in our view.

[iii] We guess anything is possible.

[vi] “Interest” and “rate” are both on the list! Don’t get mad just because they mean something totally different when combined.

[vii] Come on, it isn’t.

[viii] No pun intended. Hahahaha, who are we kidding. Of course it was intended.

[ix] Source: Brewers Association, as of 7/19/2019. Figure totals regional breweries, microbreweries and brewpubs.

[x] Ibid.

If you would like to contact the editors responsible for this article, please message MarketMinder directly.

*The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Fisher Investments editorial staff.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

You Imagine Your Future. We Help You Get There.

Are you ready to start your journey to a better financial future?

Where Might the Market Go Next?

Confidently tackle the market’s ups and downs with independent research and analysis that tells you where we think stocks are headed—and why.