Personal Wealth Management / Politics

What If, Jeremy Corbyn Edition

No politician is inherently bad (or good) for markets.

Editors’ note: Our political commentary is nonpartisan and aims to assess policies’ potential market impact only. We favor no political party or politician and believe political bias is a dangerous investing error.

What would a Prime Minister Jeremy Corbyn mean for UK stocks?

This time last year, we didn’t think we would need to explore this question in depth until 2020. But then Theresa May called a snap election, Labour made a late surge, and hyperbolic headlines like “How to Corbyn-proof Your Portfolio” started popping up. They went away just as quickly after May formed a minority government, but with her grip on power looking ever-more fragile and Labour polling eight points above the Tories, they have returned. Major financial firms warn of “disaster” if Corbyn and Labour take power. One called the prospect of a Corbyn-led Britain “Cuba without the sunshine.” Another called it “a nightmare scenario for the pound.” While anything is possible—and it is far too early to handicap the likelihood Corbyn actually becomes PM—we think the world needs to take a deep breath. Stocks, like us, are politically agnostic. They don’t prefer or automatically hate any party or politician. And they often behave differently than most expect. If Corbyn becomes PM, there is every chance UK stocks will have already priced in the fear and surprise investors in a good way—just as they did after many other left-leaning politicians gained power in recent decades.

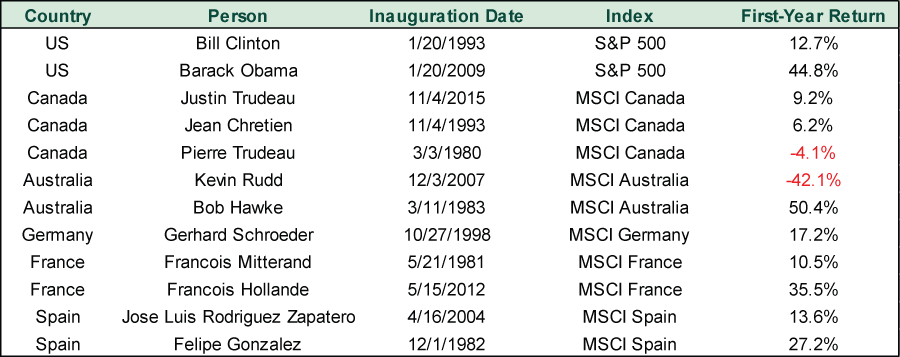

First, some history. Exhibit 1 shows returns during some left-of-center world leaders’ first year in power. We imagine many of you will quibble with our inclusion of US Presidents Bill “Third Way” Clinton and Barack Obama, but don’t let hindsight trip you up. Neither gentleman ran what we’d call a moderate campaign. Both barnstormed for single-payer health care and other standard far-left platforms. They moderated only after they were in office for a while. Les deux François also took office as dyed-in-the-wool socialists before moderating in office. Monsieur Hollande scared the pants off most investors in 2012 by pledging, among other things, a 75% tax on incomes over €1 million.

Exhibit 1: Major Developed-World Left-Leaning Leaders Since 1980

Source: FactSet, as of 12/18/2017. Total returns in local currencies to eliminate skew from conversion to US dollars. Dataset excludes second terms and presidents/prime ministers who succeeded left-leaning leaders.

In this sample set of 12, first-year returns were positive 10 times. The two negative instances—Pierre Trudeau in Canada and Kevin Rudd in Australia—had little to do with either gent. Canadian stocks suffered a sharp correction when Trudeau won, but they bottomed on March 27 and reached fresh highs that August—and kept rising until a global bear market began in late November. As for Rudd, we trust you will agree he didn’t start the global financial crisis that began in October 2007 or dictate the US government’s haphazard response when large banks imploded the following autumn.

While longer-term returns were positive after the rest of these guys took office, that doesn’t mean it was a straight shot up. In many cases, stocks tumbled for a bit as markets priced in investors’ fear of anti-business policies. We saw this with the elder Trudeau, and we saw it in France with Hollande. The MSCI France fell -15.3% from 3/16/2012 – 6/1/2012, underperforming during a global market correction as investors came to grips with the prospect of a President Hollande with a legislative majority.[i] But from June 1 through year-end, French stocks soared, outperforming the world as investors moved past the fear. Markets dealt similarly with Mitterand, Zapatero, Schroeder and others.

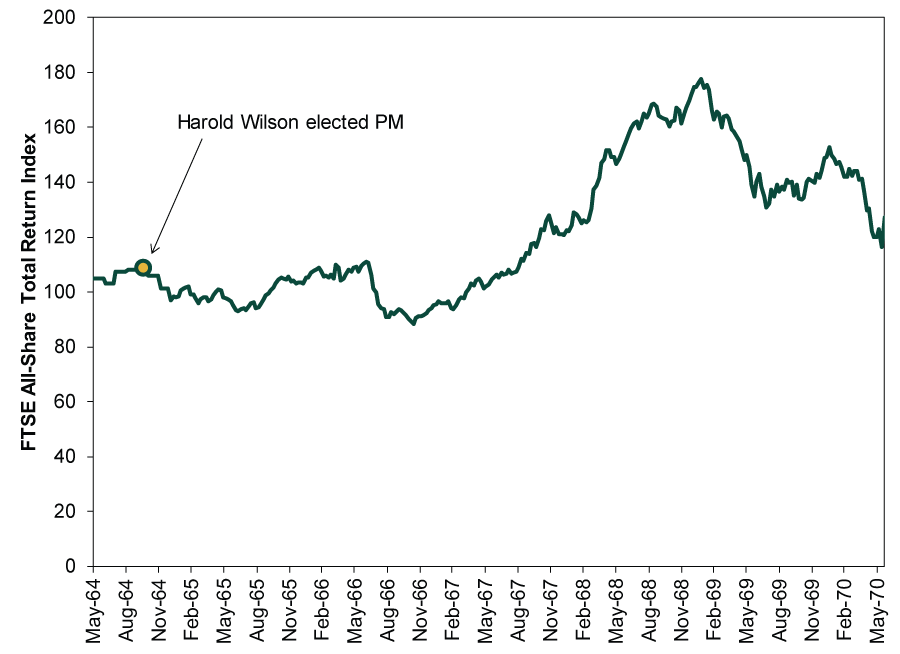

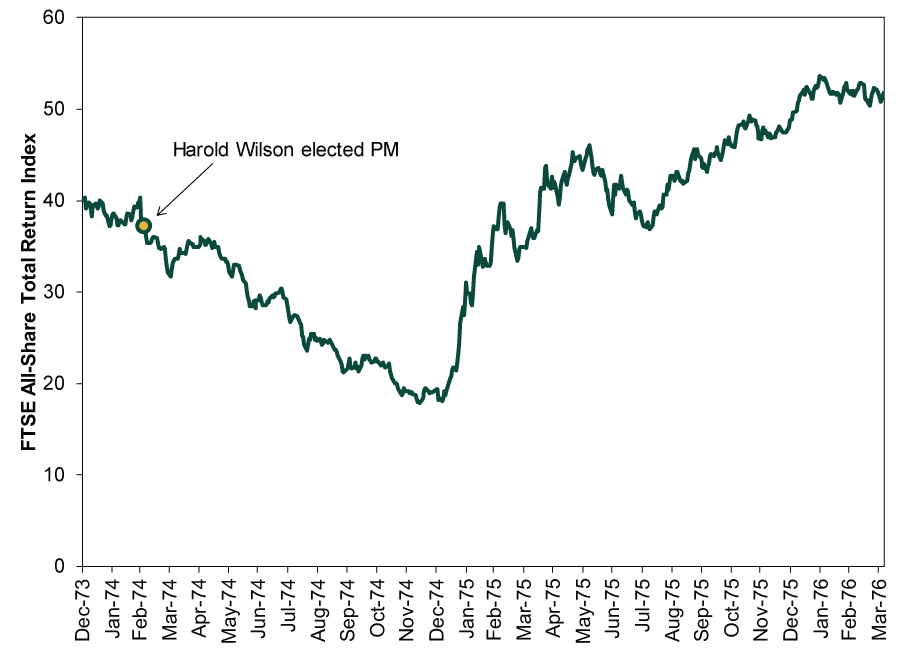

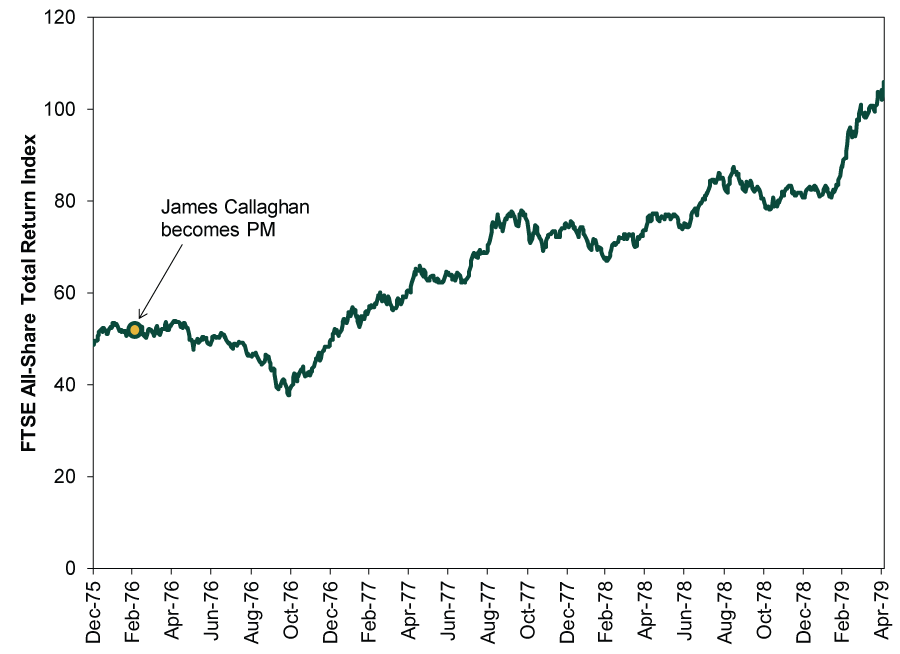

The UK has a similar history under Labour prime ministers—and not just those named Tony Blair. While Blair campaigned as the Labour version of Margaret Thatcher, the two Labour prime ministers before him—Harold Wilson and James Callaghan—were much more traditional social democrats. Wilson was prime minister twice—first from 10/16/1964 – 6/19/1970 and then, after four years of Conservative Ted Heath, from 3/4/1974 – 4/5/1976. Callaghan succeeded him, staying in office from 4/5/1976 – 5/4/1979. Exhibits 2 – 4 show the FTSE All-Share Index under each.

Exhibit 2: UK Stock Returns Under Harold Wilson

Source: Global Financial Data, Inc., as of 12/18/2017. FTSE All-Share total return in GBP, 7/31/1964 – 6/19/1970. Monthly returns through 12/31/1964 and weekly returns thereafter.

Exhibit 3: UK Stock Returns Under Harold Wilson, Redux

Source: Global Financial Data, Inc., as of 12/18/2017. FTSE All-Share total return in GBP, daily, 12/31/1973 – 4/5/1976.

Exhibit 4: UK Stock Returns Under James Callaghan

Source: Global Financial Data, Inc., as of 12/18/2017. FTSE All-Share total return in GBP, daily, 12/31/1975 – 5/4/1979.

When Wilson took office the first time, UK investors hadn’t seen a Labour prime minister since Clem Attlee held the office from July 1945 – October 1951. Considering Attlee nationalized about one-fifth of the British economy, it seems fair to say some uncertainty accompanied the first Labour prime minister in 14 years. Yet UK stocks did well for most of his tenure. When he took his second turn at the helm, he was a known quantity, but he happened to take power during a global bear market, thumping UK stocks for most of 1974. Yet Britain participated in the global recovery that began toward the end of the year and did well through the end of his term, even though Wilson raised the highest income tax rate to 83%. They also rose under Callaghan, even as he presided over the Winter of Discontent.

For investors today, the question isn’t whether Corbyn is more to the left of these earlier Labour prime ministers. Rather, will economic policy under a Corbyn government be as anti-market as feared? Corbyn himself might support renationalizing energy utilities, rail and other formerly public entities, but that doesn’t mean all Labour MPs will fall in line. Their internal divisions—and strong anti-Corbyn contingent—are well-documented. As for other economic proposals, Corbyn’s last election manifesto called for a top income tax rate of 50%—exactly where Gordon Brown put it in 2010 (and where David Cameron kept it until 2013). While some have noted that the reduction of some high earners’ pension allowances could raise some folks’ effective top tax rate to 67.5%, Britain has survived higher, and history overwhelmingly shows neither tax hikes nor tax cuts have much discernible market impact for good or ill. They are only one economic driver. Similarly, while Corbyn proposed raising corporate taxes from 19% to 26% by 2020, that would put corporate rates below where they were under the supposedly business-friendly Tony Blair. And even further below the Thatcher era. Oh, and below the US (at least for a couple more days), which thrived for decades with the developed world’s highest corporate tax rate. Hence why we’re sort of tempted to call Corbyn’s socialist aura more marketing fluff than genuine—like any good politician, he knows how to read the zeitgeist and seize the moment.

Always beware political bias. While people see parties and politicians as pro- or anti-business, markets don’t care about personalities and reputations. Sentiment toward a given candidate can influence returns in the short term, but longer term, markets weigh reality. Often, leaders thought anti-business end up much less radical than feared once in office, bringing markets relief and big rallies. Conversely, it isn’t unusual for markets to underperform when someone everyone saw as totally pro-business ends up much less radical than hoped, shattering dreams of big-bang deregulation. Regardless of their leanings, most politicians moderate once in office, concerned more with poll numbers and the next election than ideological purity.

That doesn’t mean a Prime Minister Corbyn would be guaranteed to moderate, but there is pretty strong historical precedent. Hollande and Mitterand moderated. So did Brazil’s Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. German Socialist Gerhard Schroeder overhauled labor markets, making it easier to hire and fire workers. Gridlock, opinion polls and economic reality could easily force Corbyn’s hand, just as they forced Hollande’s, Mitterand’s and Clinton’s. “Straight talking, honest politics” is just a slogan, after all.

[i] Source: FactSet, as of 12/18/2017. MSCI France total return in EUR, 3/16/2012 – 6/1/2012.

If you would like to contact the editors responsible for this article, please message MarketMinder directly.

*The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Fisher Investments editorial staff.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

You Imagine Your Future. We Help You Get There.

Are you ready to start your journey to a better financial future?

Where Might the Market Go Next?

Confidently tackle the market’s ups and downs with independent research and analysis that tells you where we think stocks are headed—and why.