Personal Wealth Management / Market Analysis

In Our View, British Rate Hikes Aren’t Bearish, Either

Our research shows stocks and UK bond yields usually do just fine after the BoE raises rates.

The Bank of England (BoE) meets Thursday, and if the financial commentators we follow are any indication, it seems the whole financial world expects policymakers to set the Bank Rate at 0.5%. In the past, this was generally considered low—indeed, when former BoE chief Mervyn King set the Bank Rate there at the end of 2007 – 2009’s financial crisis, it was an all-time low.[i] But then his successor, Mark Carney, tested the lower bound further with a 25-basis point rate cut after the Brexit vote.[ii] A couple of rate hikes and one pandemic later, Carney’s successor, Andrew Bailey, dropped the rate down to 0.1% in March 2020.[iii] Now, if the BoE acts as analysts we follow expect, the move to 0.5% will be the second-straight rate hike—a first since 2004.[iv] Many financial commentators we follow are pencilling in several more rate hikes in the coming months, and many of them warn rate hikes will send long-term bond yields skyward and stocks spiraling lower.[v] Yet, we think history disagrees.

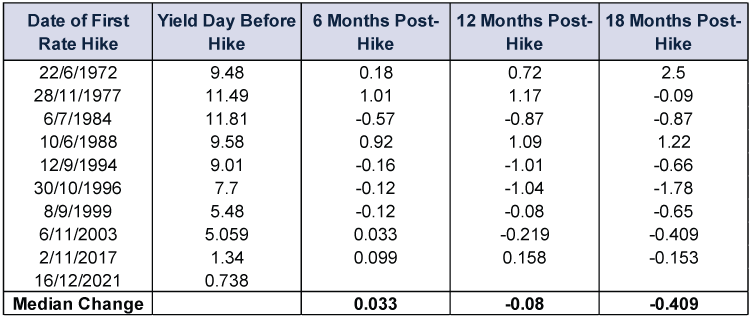

Exhibit 1 shows UK stock returns before and after the first rate hike in every completed tightening cycle since the MSCI UK Index’s 1969 inception. As it demonstrates, returns after rate hikes are positive much more often than not, with only two rate hikes occurring within a year of a global bear market (a prolonged, fundamentally driven, broad equity market decline of -20% or worse) beginning.[vi] Our historical analysis shows the BoE wasn’t the bear market’s proximate cause on either occasion. In the early 1970s, we think it was the fallout from transatlantic price controls and the oil shock. In 2000, our research shows it was the Tech bubble’s implosion, which rippled globally after starting in the US that March. The only other time when returns after a rate hike were negative over the next two years was following November 2017’s increase. Then, UK stocks got caught up in global stocks’ twin corrections in 2018 (sentiment-driven declines of around -10% to -20%), which stemmed first from trade war fears and then, at yearend, from the wave of hedge fund selling we discussed a few weeks back.[vii] The BoE’s rate hike preceded the first correction by nearly three months.[viii]

Exhibit 1: BoE Rate Hikes and UK Stocks

Source: Bank of England and FactSet, as of 31/1/2022. MSCI UK Index price returns, 22/6/1971 – 16/12/2021.

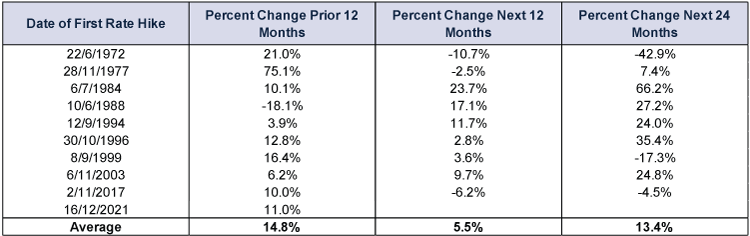

Global returns tell a similar tale, as Exhibit 2 shows, with returns higher on several occasions. In our view, this doesn’t mean UK stocks are inferior—rather, we think it demonstrates that most of the time, monetary policymakers start hiking rates relatively late in a bull market (a long period of generally rising equity prices). We think this matters because the UK’s stock market tilts heavily to value-orientated stocks—which tend to carry relatively lower price-to-earnings ratios and more debt, making them more sensitive to economic conditions, and which tend to return more money to shareholders via dividends and share buybacks and invest less in growth endeavours. These types of stocks usually lead in a bull market’s initial stages.[ix] By contrast, growth-orientated stocks—those that generally have higher valuation metrics like price-to-earnings ratios and focus on reinvesting profits into the core business to expand over time, making their profits relatively less sensitive to economic ups and downs—usually outperform in bull markets’ later stages. Our historical research shows this often leads the UK to underperform in maturing bull markets. Note that on the two occasions UK stocks did better than global during the first year after an initial rate hike—1994 and 2003—the hikes came early in those respective bull markets, before growth assumed lasting leadership.

Exhibit 2: BoE Rate Hikes and Global Stocks

Source: Bank of England and FactSet, as of 31/1/2022. MSCI World Index price returns, 22/6/1971 – 16/12/2021.

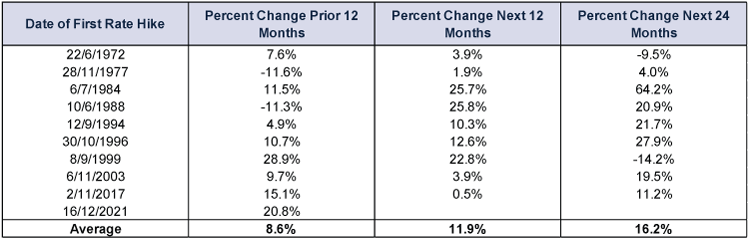

Based on historical data, long-term gilt yields appear similarly unbothered by BoE rate hikes, overall and on average. As Exhibit 3 shows, 10-year gilt yields fell much more often than not after rate hike cycles kicked off. The median yield change was barely positive over the next 6 months and negative over 12 and 18 months. We think the reason for this is fairly simple: Markets pre-price widely expected moves (or pre-emptively incorporate information into share prices), and from what we have observed, the BoE is much more a rate follower than a rate setter. Meaning, we think policymakers tend to react to past inflation and data, whilst our research shows long-term rates move ahead of expected inflation. So, in our view, by the time the BoE raises rates in hopes of curbing inflation, long rates have generally moved both on the expectation of the inflation the BoE is reacting to and the expectation of the rate hike itself. We think that saps surprise power, usually leaving rates to fall in the aftermath. Bonds, like stocks, love defying conventional wisdom and broad expectations, in our view.

Exhibit 3: BoE Rate Hikes and 10-Year Gilt Yields

Source: Bank of England and Global Financial Data, Inc., as of 31/1/2022. UK 10-year benchmark government bond yield, 21/6/1972 – 15/12/2021.

Some financial commentators we follow argue rates are especially likely to rise this time because the BoE plans to start letting maturing gilts roll off its balance sheet once the Bank Rate reaches 0.5%. Here, too, we don’t think the consensus view is likely to come true. Take the US for example: 10-year US Treasury yields fell, cumulatively, whilst the US Federal Reserve (Fed) let its balance sheet shrink late last decade.[x] Rates did rise at times during that stretch, but the move wasn’t huge or sustained, and it didn’t appear to disrupt the economy.[xi] Two, again, we think bond markets are forward-looking. The BoE released its plan to let its balance sheet run down way back in August 2021.[xii] At the time, Bailey said the Monetary Policy Committee would cease reinvesting the proceeds of maturing bonds when the Bank Rate rose to 0.5% and start selling bonds once it hit 1%. That meeting occurred on 5 August, when 10-year gilt yields were at 0.525%.[xiii] They have since risen over 60 basis points, to 1.191% on 10 January, before settling back down a bit.[xiv] That sure looks to us like markets pricing in impending action.

Mind you, we don’t think rising long rates are a bad thing. According to our research, stocks don’t move opposite bond yields, which is a critical point most bearish theories today seemingly ignore. Moreover, we think rising long rates help keep the yield curve (a graphical representation of one issuer’s interest rates across the spectrum of maturities) steeper, which over a century of economic theory and data show is generally positive for the economy looking forward.[xv] We aren’t suggesting this is a market timing tool, but it does suggest capital is likely to keep flowing to productive people and businesses, which we think adds to economic growth and supports corporate profits. Technically speaking, that is what you own a stake in if you own stocks—the future earnings of publicly traded corporations. We think it is a telling sign of sentiment that many financial commentators we follow warn against an economic positive—that suggests to us there is plenty of room here for reality to surprise and help propel stocks up the proverbial wall of worry bull markets are often said to climb. That said, we don’t think that precludes sentiment-driven swings and negativity in the near term, as the past few weeks attest, but we do think it is likely to help stocks rise later this year, as the fog of uncertainty gradually fades.[xvi]

[i] Source: Bank of England, as of 1/2/2022. The Bank of England changed the rate on 5/3/2009.

[ii] Ibid. The Bank of England changed the rate on 4/8/2016.

[iii] Ibid. The Bank of England changed the rate on 19/3/2020.

[iv] Ibid. The Bank of England hiked rates four times in 2004, 5/2/2004, 6/5/2004, 10/6/2004 and 5/8/2004.

[v] “Bears in Charge Due to Inflation Worries,” Staff, Reuters, 31/1/2022.

[vi] Source: The Bank of England, as of 1/2/2022. Statement based on MSCI World Index returns with net dividends.

[vii] Source: FactSet, as of 1/2/2022. Statement based on MSCI UK Index price returns with net dividends. The first 2018 correction began and ended 26/1/2018 – 23/3/2018. The second 2018 correction began and ended 21/9/2018 – 25/12/2018.

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Source: FactSet, as of 1/2/2022. Statement based on MSCI World Growth and Value Index returns with net dividends.

[x] Source: FactSet and US Federal Reserve, as of 1/2/2022. Statement about interest rates based on 10-year US Treasury yield.

[xi] Ibid.

[xii] Source: “Monetary Policy Report Press Conference,” Opening Remarks by Andrew Bailey, Governor, Bank of England, 5 August 2021.

[xiii] Source: Global Financial Data, Inc., as of 31/1/2022.

[xiv] Ibid.

[xv] Source: A Monetary History of the United States: 1867 – 1960. Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz. Princeton University Press. 1993.

[xvi] Source: FactSet, as of 1/2/2022. Statement based on MSCI World Index return with net dividends. 31/12/2021 – 31/1/2022.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights.

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

See Our Investment Guides

The world of investing can seem like a giant maze. Fisher Investments UK has developed several informational and educational guides tackling a variety of investing topics.