Personal Wealth Management / Economics

A Pre-UK Election Look at Non-Election UK Data

Some interesting nuggets from monthly trade and GDP.

The UK holds a general election on Thursday, and this article is not about that. We will not even try to interpret today’s GDP and trade data in light of what they mean for voters, because that would be a) silly and b) myopic. Rather, we think these data are worth a look for what they show about sentiment and, we guess, how UK businesses are dealing with the B-word.[i]

Headlines discussing today’s reports offered two main messages. On the GDP front, they focused on the three-month change and pronounced the UK economy “flat lining.” On the trade front, they focused on the burgeoning trade deficit but, rather than freak out about the current account, they cited surging imports as the lone bit of evidence consumers and businesses were stockpiling ahead of October’s Brexit deadline (which, of course, came and went). The subtext? Even a pre-hard-Brexit stockpiling surge wasn’t enough to rescue the UK economy from dastardly zero percent growth, evidence of a weakening economic backdrop.

As ever, we think reality is juuuuuust a bit more complex. Starting with GDP: This was the monthly report for October. While we get the temptation to emphasize the three-month change since GDP is most often reported quarterly, part of the benefit of a monthly report is a more granular look at short-term trends. There is a lot of noise, but occasionally it is interesting noise, which we think was the case in October. You see, monthly GDP was flat, but that followed contractions in August and September. Manufacturing output rose 0.2% m/m, also snapping two straight contractions, while services output rose 0.2% after a flat September and -0.1% August. The main negatives were in the long-suffering mining industry, which includes oil and natural gas, and always-volatile construction. One month doesn’t make a trend, but the word that springs to mind for October is “stabilization.”

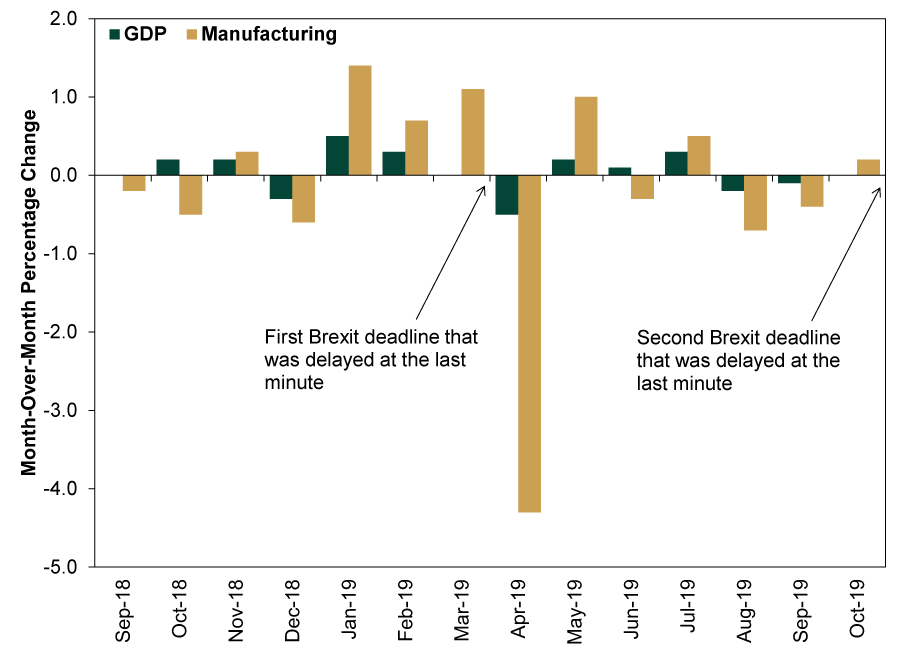

The shifting Brexit deadline’s influence is tough to assess. In IHS Markit/CIPS’ Purchasing Managers’ Indexes (PMIs), survey respondents did report some stockpiling in September and October, particularly in manufacturing, but not to the extent they did before this year’s first Brexit deadline, March 29. Back then, auto manufacturers even brought forward annual closures for retooling! Exhibit 1 shows monthly GDP and manufacturing output surrounding both deadlines, so you can draw your own conclusions.

Exhibit 1: Data and Deadlines

Source: Office for National Statistics, as of 12/10/2019. Monthly GDP and manufacturing output, seasonally adjusted, September 2018 – October 2019.

It does seem fair to say businesses stockpiled to a lesser extent this time, but we think there are non-economic reasons for this. One, they were probably still working through inventories amassed the last time around. Two, since politicians had already broken the taboo of delaying Brexit, businesses had good reason to believe they would do so again, avoiding the supposed cliff edge of a no-deal Brexit. If you can avoid an unnecessary inventory build and the months-long hangover that typically follows, you generally try to avoid it—just good business sense. Even the auto industry seemed to more or less take the second deadline in stride. Not all manufacturers planned shutdowns for early November, and those that did—and proceeded with them—took much shorter breaks than before. To the extent UK businesses were savvy enough to avoid short-term disruptions, we think that is good, not bad. It also gives them more bandwidth to unleash longer-term investments once Brexit is finally settled and its details known.

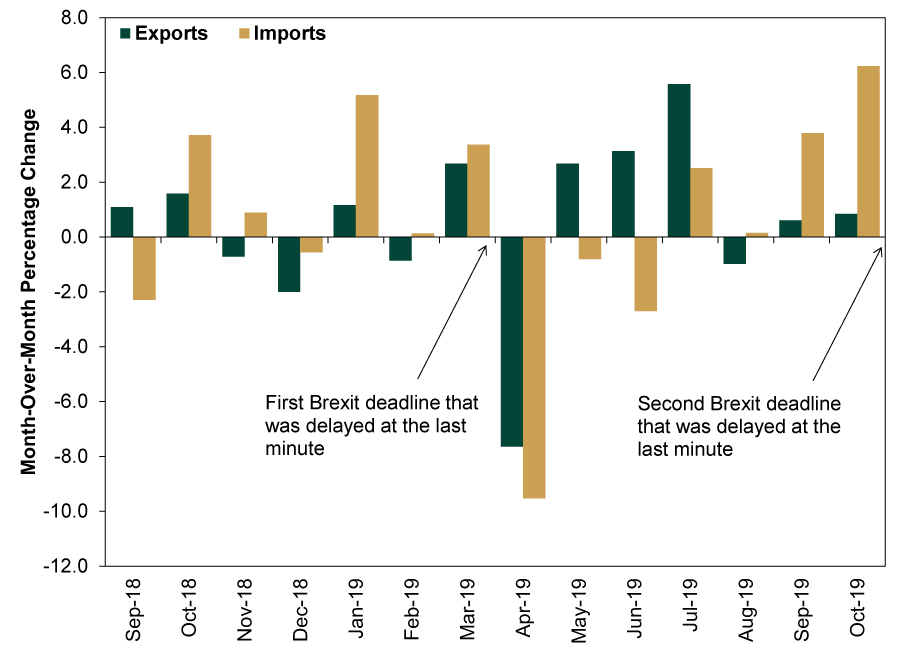

Moving on to trade, Exhibit 2 plays the same game.

Exhibit 2: More Data and Deadlines

Source: FactSet, as of 12/10/2019. Monthly exports and imports, seasonally adjusted, September 2018 – October 2019.

Here, too, mild stockpiling seems like a fair explanation for fast import growth. But exports are a tad more interesting. The hangover after the first scrapped Brexit deadline was short. Exports then grew in five of the next six months. To us, this suggests UK exporters are perhaps more immune to the shifting deadlines than the rest of the economy, which sort of defies conventional wisdom. You would think they would be far more sensitive, given the uncertainty over the tariffs and customs rules they will face once Brexit finally happens. You would think, therefore, that businesses would have been busy rerouting supply chains around the UK, just in case. But that doesn’t appear to have happened, which we think speaks to quiet global confirmation that the UK will be a good place to do business for the foreseeable future.

As always, none of these data are predictive. GDP, trade and all other measures of output are backward-looking. Stocks today are looking toward the next 3 – 30 months, and how the UK economy did in early autumn doesn’t dictate how it will do next year and beyond. But overall, we think the data are more encouraging than prevailing sentiment would have you believe, which seems like a nice backdrop for UK stocks—especially once political and Brexit uncertainty finally start falling.

[i] Brexit, of course.

If you would like to contact the editors responsible for this article, please message MarketMinder directly.

*The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Fisher Investments editorial staff.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

You Imagine Your Future. We Help You Get There.

Are you ready to start your journey to a better financial future?

Where Might the Market Go Next?

Confidently tackle the market’s ups and downs with independent research and analysis that tells you where we think stocks are headed—and why.