Personal Wealth Management / Politics

Germany Gets Gridlock Again

Whatever coalition emerges probably can’t pass much.

Editors’ Note: MarketMinder is politically agnostic. We prefer no politician nor any party and assess political developments for their potential economic and market impact only.

The results are in, and German voters have elected—wait for it—gridlock. No party took a majority in Sunday’s federal election, and it is far from clear which party will head the next government and who will replace Angela Merkel as chancellor—as we (and most observers) expected. Coalition negotiations could very well take months. Yet for markets, this all amounts to political stability and the extension of the status quo, which has long been a fine backdrop for German stocks.

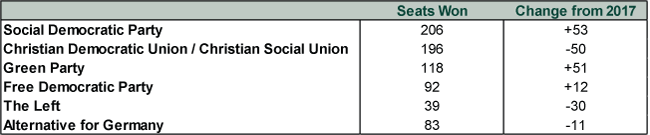

Heading into the vote, the center-left Social Democratic Party (SPD) was polling just ahead of Merkel’s center-right Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and its Bavarian sister party, the Christian Social Union (CSU). Those polls proved more or less right, with the SPD winning 25.7% of the vote and the CDU and CSU combining for 24.1%. The SPD took a small plurality of the Bundestag’s 735 seats.

Exhibit 1: German Election Results

Source: German Federal Returning Officer, as of 9/27/2021. The South Schleswig Voters’ Association took one seat.

All parties fell well short of the 368 needed to form a majority, ensuring Germany will get another coalition government—the post-War norm. As it stands, few expect the SPD and CDU/CSU to renew their eight-year-old coalition, as both parties have stated their preference for something new. Voters, who upped their support for the Greens and pro-business Free Democratic Party (FDP), seem to agree. Mathematically, any new coalition would require one of the main parties to join with both the FDP and Greens, making them joint kingmakers. But they are also odd bedfellows, as they have little common ground ideologically—the FDP is right-leaning and founded on free-market principles, while the Greens lean left and see a large role for the state in directing resources. When Merkel tried to form a coalition with both parties after 2017’s election, talks collapsed after several fruitless months.

In most European parliamentary democracies, the head of state (be it the monarch or president) assesses the results and then asks the leader of the top-finishing party to form a government. If that party doesn’t have a majority, the leader then sets out negotiating with potential coalition partners. In Germany, however, it is a free for all. The president doesn’t tap anyone, and all parties are free to pursue their own coalitions simultaneously. As a result, SPD leader Olaf Scholz and CDU leader Armin Laschet each stated they would attempt to build a coalition with the FDP and Greens Monday. Both leaders’ personalities thus came into focus. Scholz, who has a reputation for calm leadership after serving as Merkel’s finance minister, acted the part of chancellor in waiting. Laschet, meanwhile, ignored calls from within his party to concede and resign following the CDU’s worst drubbing since WWII, illustrating the divisions that have plagued his leadership from the start.

But counting the CDU out would be wrong. For one, neither the SPD nor the CDU/CSU wanted to renew their coalition after 2017’s election—but that is exactly what they ended up doing. Two, FDP leader Christian Lindner has said his party prefers to be part of a center-right coalition. No doubt he and other FDP bigwigs remember the thrashing they took in 2013’s election as supporters punished their participation in the Greek, Portuguese and Irish bailouts, which went against the party’s traditional values. If supporting a center-right government landed them in such hot water with voters then, rubber-stamping policies further to the left may not strike FDP leaders as a wise endeavor now. But coalition building isn’t about ideological purity—it is about power and influence. Leaders might see major cabinet posts as enough of a win.

If recent history is a guide, negotiations will likely stretch on for months, delaying Merkel’s retirement (she remains caretaker chancellor). Scholz and Laschet have talked of having a new government by Christmas, which seems a tad optimistic. Heck, there isn’t much indication either party will be involved in serious talks anytime soon. The FDP and Greens are reportedly beginning talks to see what—if any—common ground they have and stake out a potential joint negotiating position. But even getting that far will require either party to concede on whether to reach out to the SPD (the Greens’ preference) or CDU/CSU (the FDP’s) first. Oh, and they will likely also need to find some overlap on taxes, infrastructure spending and the country’s constitutional deficit limit, which the FDP wants to reinstate from its temporary pandemic hiatus and the Greens want to repeal. All of these issues are potential deal breakers.

We suggest not getting bogged down in all of the political theatrics that will probably ensue, which will likely dive deep into what this-or-that coalition pairing could emphasize, and potentially explore the leanings and interests of various potential ministers. For stocks, that stuff is a sideshow. Policies, not personalities, determine politics’ market impact. A slow-moving coalition process that yields a fractured government is a recipe for legislative inaction. The primary combination investors feared—a leftist grouping of the SPD, Greens and Left—is already off the table mathematically. (The far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) was also feared at one point years ago, yet most observers today realize there is virtually no chance they are invited to join any potential coalition.) In either of the possible three-party coalitions, divides between the FDP and Greens probably torpedo any major legislation. If both three-party possibilities fall through and the SPD and CDU/CSU join forces again, we have already seen what that looks like. In all cases, major changes seem unlikely. We might see taxation and spending tweaks at the margins, but there aren’t enough votes to repeal the debt brake—not with the CDU/CSU and FDP opposed to doing so.

For stocks, this extended gridlock should be a-ok—as it has been for years in Germany. Markets are generally happiest when governments can’t alter property rights or otherwise discourage risk-taking and investment. Gridlock thus lowers legislative risk aversion, giving stocks a few less things to fear. Protracted stalemates aren’t bearish, either. Dutch voters went to the polls in mid-March, and the Netherlands still doesn’t have a government—yet the country has outperformed European stocks cumulatively since the election. Similarly, German stocks beat European stocks during the nearly six-month stalemate after 2017’s election. We think markets simply saw what voters couldn’t: A government that can’t form for months on end can’t rock the boat much.

If you would like to contact the editors responsible for this article, please message MarketMinder directly.

*The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Fisher Investments editorial staff.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

You Imagine Your Future. We Help You Get There.

Are you ready to start your journey to a better financial future?

Where Might the Market Go Next?

Confidently tackle the market’s ups and downs with independent research and analysis that tells you where we think stocks are headed—and why.