Personal Wealth Management / Market Volatility

Oil's Big Jump in Perspective

With some historical context and a look at global oil supplies, Monday’s oil volatility and the Saudi production disruptions don’t look awful for the global economy or markets.

Oil prices endured one of their biggest jumps in recent memory on Monday, following drone strikes on one of Saudi Arabia’s largest oil fields and a crude oil processing facility. As a result of the attacks, around half of the country’s oil output went offline Sunday, and it is unclear when it will be back at 100%. As we finalized this commentary at 1:25 PM Pacific Time Monday, US benchmark crude oil prices (West Texas Intermediate, or WTI) were up 12.9% to $61.93 per barrel on the day, while the global benchmark (Brent) rose 14.6% to $68.02 per barrel.[i] Headlines pounced on the sudden increase, speculating about the potential economic impact if it were to last. However, this all appears rather too hasty, and the evidence suggests an oil spike—even if it lingers—isn’t capable of walloping the global expansion or bull market.

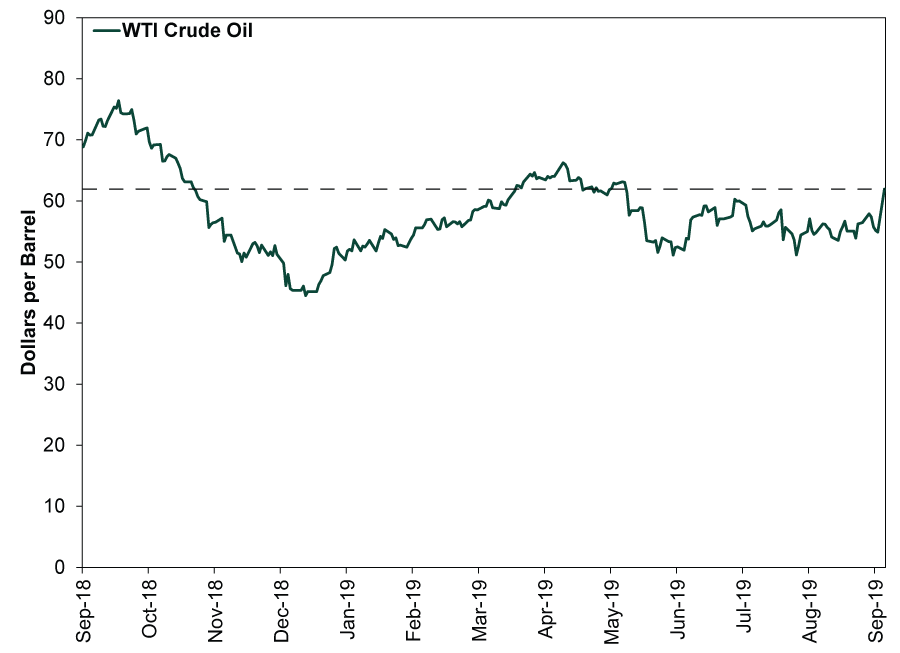

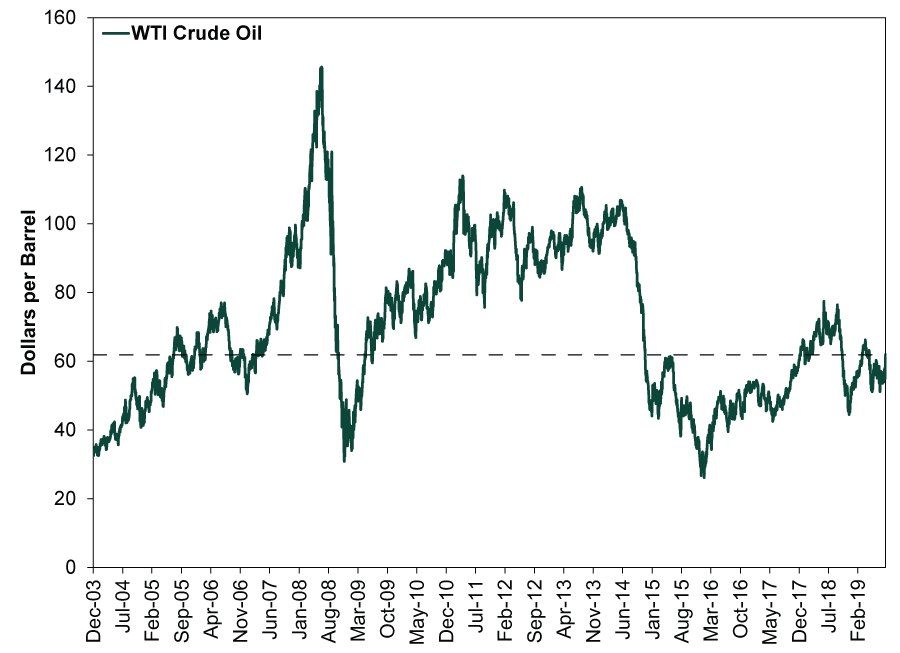

Assessing Monday’s spike requires putting it into proper context. Yes, the jump is big, but it is a jump off a rather low base. Monday’s closing oil prices were the highest since—wait for it—the end of May 2019. Exhibit 1 shows oil over the past year. For a longer perspective, Exhibit 2 shows oil over the past 15 years. Today’s prices pale in comparison to what we saw even five years ago, never mind the prior peak in 2018.

Exhibit 1: A Year’s Worth of Oil Prices

Source: FactSet, as of 9/16/2019. WTI Crude spot price, 9/17/2018 – 9/16/2019. Price on 9/16/2019 is the intraday price at 1:25 PM PDT.

Exhibit 2: A Longer Look

Source: FactSet, as of 9/16/2019. WTI Crude spot price, 12/31/2003 – 9/16/2019. Price on 9/16/2019 is the intraday price at 1:25 PM PDT.

Headlines are making a mountain out of the amount of Saudi oil output that went offline on Monday—5.7 million barrels per day (bpd), versus the country’s average output in August, 9.8 million bpd.[ii] In addition to this being about two-thirds of Saudi production, it is about 5% of global production. Yet the country, like much of OPEC, has a fair amount of spare capacity following their and certain non-OPEC nations’ coordinated effort to reduce output and battle a global supply glut in recent years. If Saudi spare capacity isn't impacted by the outage (currently unknown), they could ramp up output elsewhere to partly offset the impact. Saudi Arabia also reportedly has considerable stockpiles of previously processed crude it could use, defraying the outage's immediate impact. As for OPEC overall, production has dropped from about 35 million bpd in November 2016—when they agreed to start cutting—to 31.9 million bpd in May.[iii] Saudi Arabia is responsible for about one-third of that cut. So even if Saudi facilities take a while to come back online, other nations could help partially fill the shortfall.

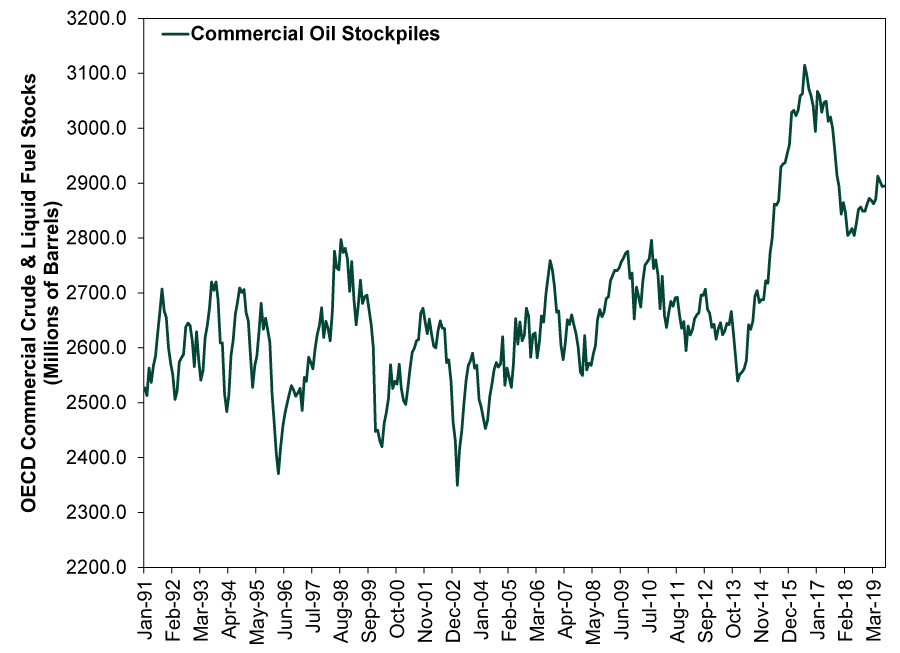

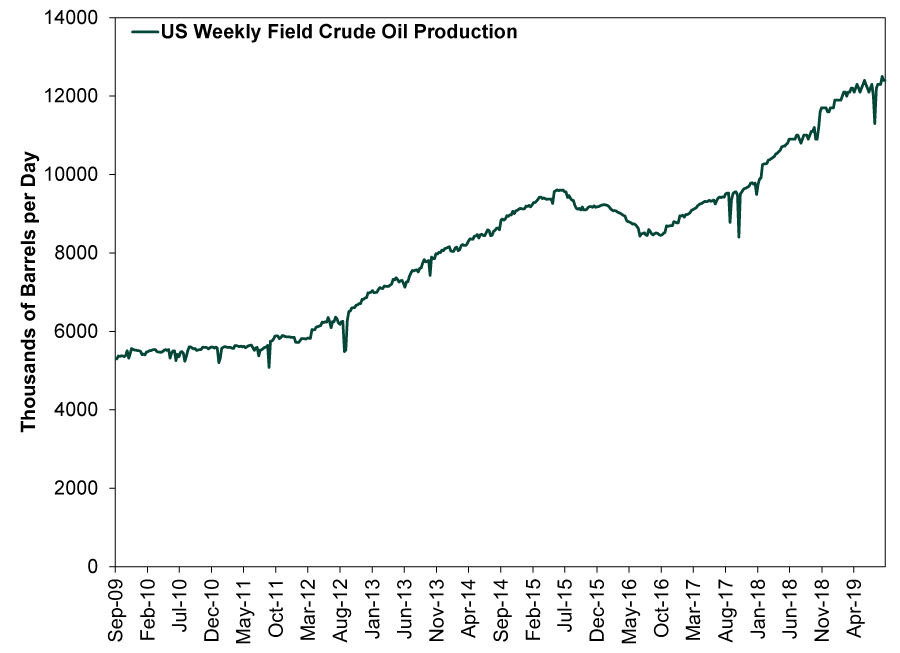

Another key consideration: Even with the recent production cuts, the world was still working through a rather sizeable oil inventory overhang, as Exhibit 3 shows. Oil stockpiles have actually increased this year to about 2.9 billion barrels despite OPEC’s efforts, thanks to US shale production soaring to 12.4 million bpd. (Exhibit 4) These days, the US, not Saudi Arabia, is the world’s swing producer.

Exhibit 3: Global Oil Stockpiles Are Up

Source: FactSet, as of 9/11/2019. OECD Commercial Crude & Liquid Fuel Stocks, Monthly, January 1991 – August 2019.

Exhibit 4: So Is US Production

Source: FactSet, as of 9/16/2019. Weekly field crude oil production, 9/11/2009 – 9/6/2019.

Between high inventories, spare OPEC capacity and surging US production, oil supply likely remains rather resilient even if Saudi output remains hampered for a while. That should help keep a ceiling over prices. Even if oil remains elevated—and rises further—it shouldn’t endanger economic growth or stocks. For one, it takes a lot less oil to produce a dollar of US GDP than it used to. Two, higher gasoline prices may cut into discretionary consumer spending, but that amounts to a shift within the broader consumer spending category—not a reduction in total spending. Just as consumer spending didn’t soar when oil prices tanked in 2014 and 2015, it shouldn’t plunge now if gas gets a bit pricier. More broadly, if the world economy could grow fine—and stocks could do great—in 2013, when WTI crude bounced between $90 and $105 per barrel, it is tough to see prices just north of $60 being some huge headwind. If anything, a modest rise improves fortunes for oil-producing nations, adding to GDP. If lasting, it could also improve small US shale oil drillers’ finances, helping ease some pressure in a shaky corner of the corporate bond market.

[i] Source: FactSet, as of 9/16/2019 at 1:25 PM PDT. WTI Crude and Brent Crude oil spot prices, 9/16/2019.

[ii] Source: FactSet, as of 9/16/2019. Average daily Saudi Arabian crude oil production, August 2019.

[iii] Source: FactSet, as of 9/16/2019. Average daily OPEC crude oil production, November 2016 – May 2019.

If you would like to contact the editors responsible for this article, please message MarketMinder directly.

*The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Fisher Investments editorial staff.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

You Imagine Your Future. We Help You Get There.

Are you ready to start your journey to a better financial future?

Where Might the Market Go Next?

Confidently tackle the market’s ups and downs with independent research and analysis that tells you where we think stocks are headed—and why.