Personal Wealth Management / Economics

A Presidential Candidate Has Thoughts on Capital Gains

We take a look at one presidential hopeful's plan to address "quarterly capitalism."

Editors' Note: Our discussion of politics is focused purely on potential market impact and is designed to be nonpartisan. Stocks favor neither party, and partisan ideology invites bias-dangerous in investing.

Last Friday, presidential hopeful Hillary Clinton announced her plan to fix "quarterly capitalism"-short-term thinking in board rooms and on Wall Street-and promote long-term investment. The reform's centerpiece: raising high earners' capital gains taxes on stocks sold between one and six years after purchase, theoretically giving firms more incentive to invest in the future instead of buying back stock to pacify short-term focused shareholders. The proposal has inspired debate, and we suspect it is only the first of many tax proposals we'll hear throughout 2016's campaign. Cutting through the noise and sociology to take an objective look at market impact is often difficult, but for investors, it is crucial-bias is deadly. So, setting aside ideology and partisan tilt, what should investors make of Clinton's proposal? In short, we wouldn't cheer or fear it. Not only is it way too early to handicap whether it becomes law, but tax changes have little relationship with market returns, and the potential impact on company behavior seems negligible.

Clinton's plan is the latest salvo in the buybacks vs. capex debate. A growing school of thought argues "shareholder capitalism" makes firms too focused on one quarter's earnings, doing their utmost to boost the bottom line and satisfy shareholders with itchy trigger fingers. Many blame this for the rise in stock buybacks, arguing rewarding shareholders discourages R&D investment and other long-term endeavors, putting America's economic dynamism (not to mention productivity, wages and hiring) at risk in the long run.

To dissuade companies from shortsightedness, Clinton offered several solutions, including increasing buyback transparency by requiring daily disclosure of executed buybacks (rather than quarterly) and reviewing shareholder activism and executive compensation tax rules. Her proposal to raise the capital-gains tax rate, however, grabbed the most attention. Currently, gains on investments held less than a year (aka short-term capital gains) are subject to ordinary income tax rates. After a year, the rate drops to 20% for the highest earners (15% for most other households). Clinton's proposal would impact the top tax bracket only, extending short-term gains from one year to two, and then slide the tax rate down from 39.6% by a few points each year to 20% by year six. Including the 3.8% Net Investment Income Tax, top earners' capital-gains tax rate would be 43.4% in those first two years.

With stronger incentives to hold stock for longer, investors would theoretically be more willing to wait for companies' long-term investments to pay off, making them less focused on stock prices (and earnings) in the here and now. Now, on theoretical grounds, we agree companies and investors alike may get caught up in quarterly numbers, and the incentives for strong earnings could influence CEOs' actions a bit. Most companies don't assess overall success over short, arbitrary calendar periods (like a quarter) as business plans often stretch a decade or more. An investment may yield a high long-term return but bleed cash early, knocking earnings-yet few would argue a company shouldn't pursue it. At the same time, the frenzy surrounding quarterly earnings can give firms incentives to boost the bottom line today, which might mean pushing off capex.

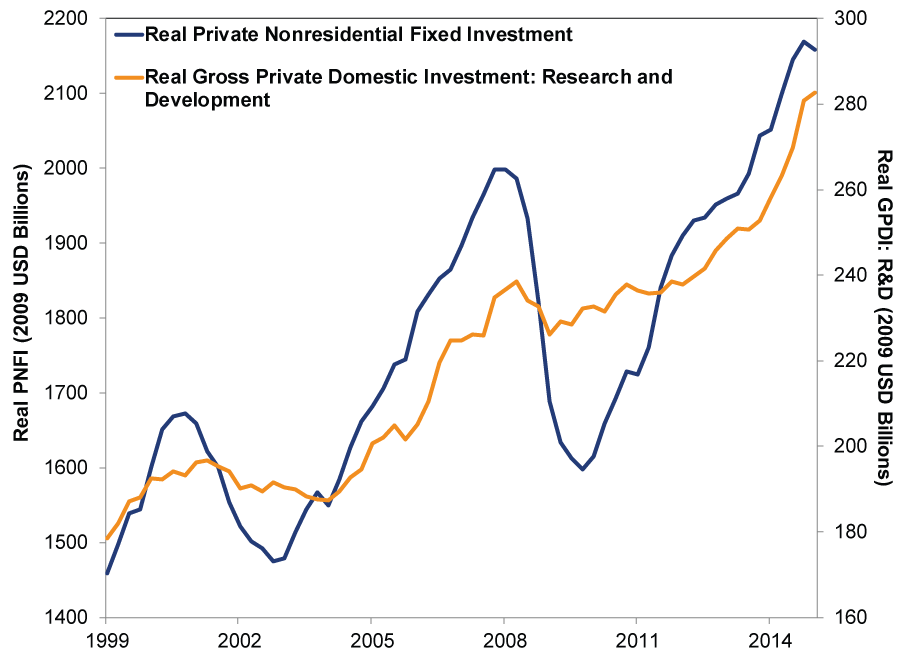

Trouble is, there is no way to quantify this-it is mostly a matter of opinion whether this mentality has reduced investment. There is no counterfactual, no way to prove investment would rise with different incentives. However, available facts don't suggest capex needs a huge artificial boost. R&D spending is at all-time highs and rising. Total business investment hit its fifth straight all-time high in Q4 2014 before pulling back a tad in Q1 as oil firms cut costs. No one knows if it would be higher or lower if buybacks were less common.[i] Hence we're inclined to view this proposal as a solution in search of a problem. (Exhibit 1)

Exhibit 1: US Business Investment and R&D Investment Since 1999

Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve, as of 7/27/2015. Quarterly Real Private Nonresidential Fixed Investment and Real Gross Private Domestic Investment: Research and Development, 1/1/1999 - 3/31/2015.

Now, we suppose companies could increase investment, and it is true business investment has grown more slowly during this cycle[ii], but that raises an interesting counterpoint: Is raising long-term investment always and everywhere a better use of capital ? Investment for investment's sake isn't always wise. If firms overextend themselves today, they could be in real trouble when the next downturn hits-risk always exists. Plowing a bunch of working capital into a long-term project can reap wonders if it pays off, but there is such a thing as unproductive investment. For example, if a hypothetical car company named, say, Cord Motor Company spends billions on a new car called the Flugo, and it doesn't pan out, that can be a big hole to dig out of. If companies are being more judicious about the risks they take, that isn't necessarily a bad thing.

So we're sort of skeptical tweaking shareholders' incentives will much impact the Executive Suite's risk aversion. We're also skeptical the proposal would improve the overall deployment of capital. For one, it hits a tiny sliver of the market. Retirement accounts (pensions, IRAs and 401(k)s) aren't subject to capital gains taxes, and most retail investors aren't in that top tax bracket. For most folks, it'll be business as usual. Buybacks get a bum rap these days, but returning cash to shareholders lets them deploy funds elsewhere, investing in new companies. Rules discouraging this would effectively limit the amount folks have to invest elsewhere, which could reduce capex over time-a high and sliding tax-rate scale would likely compound this "lock-in effect."

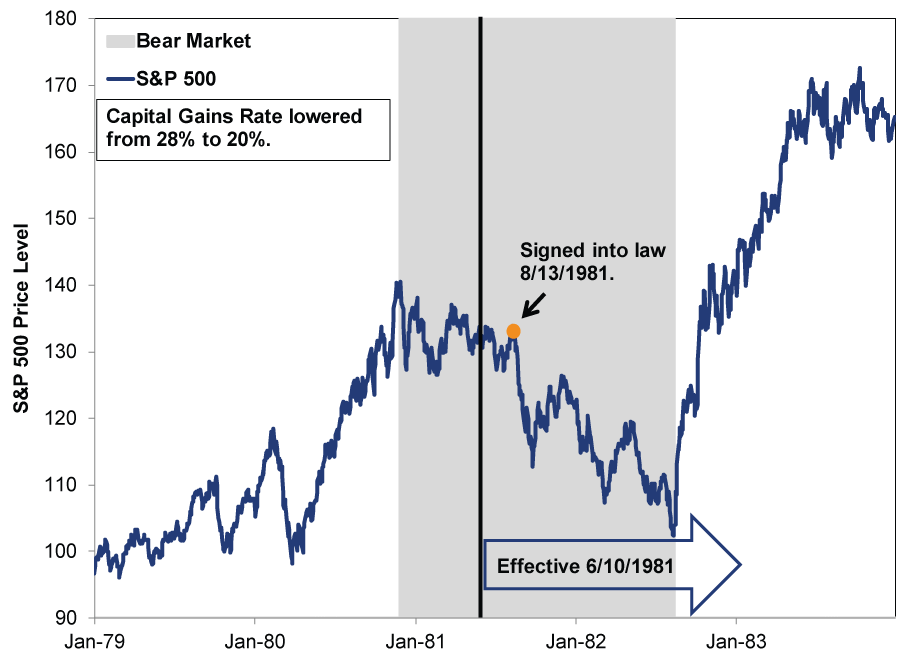

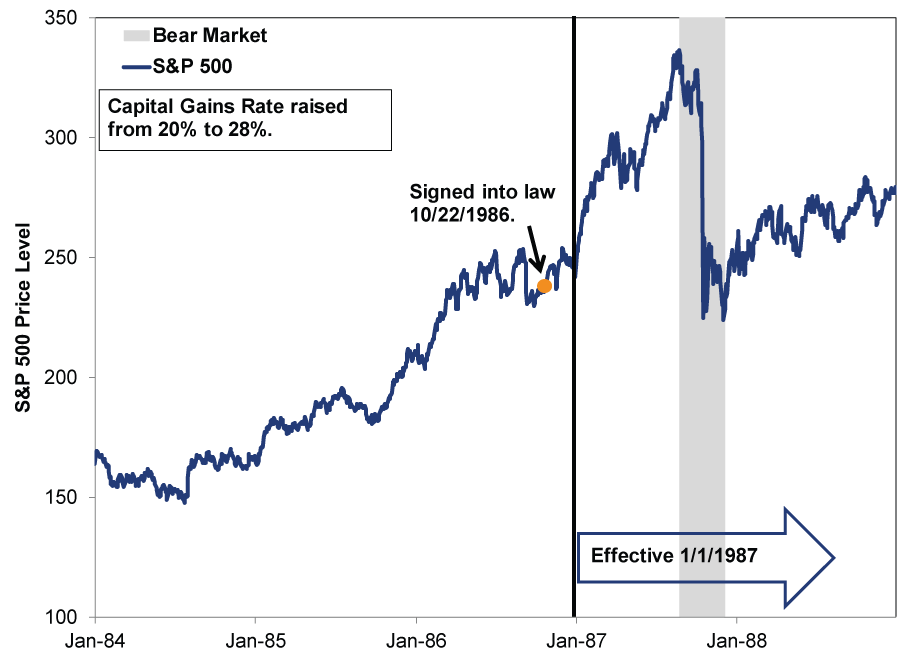

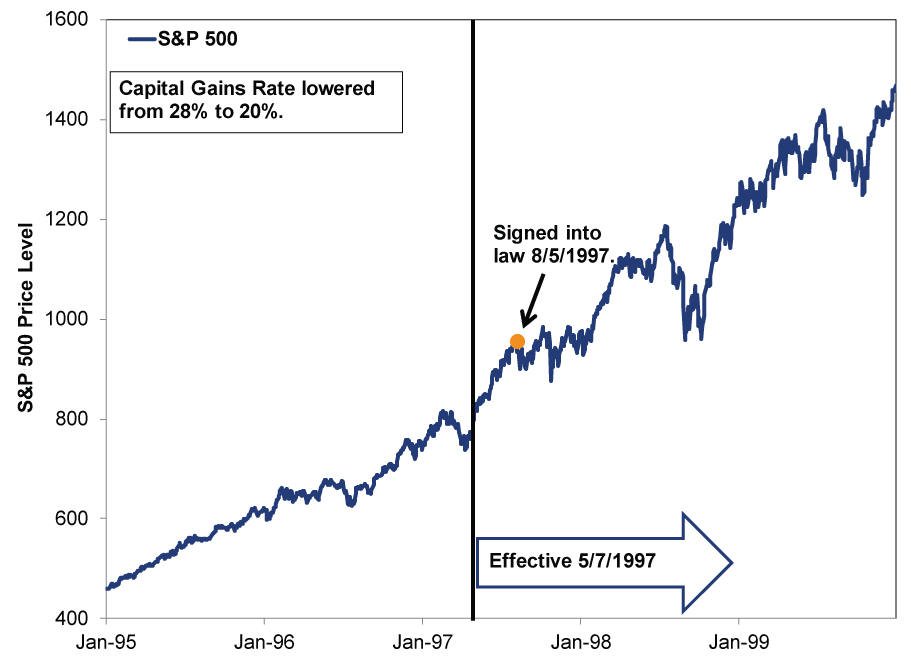

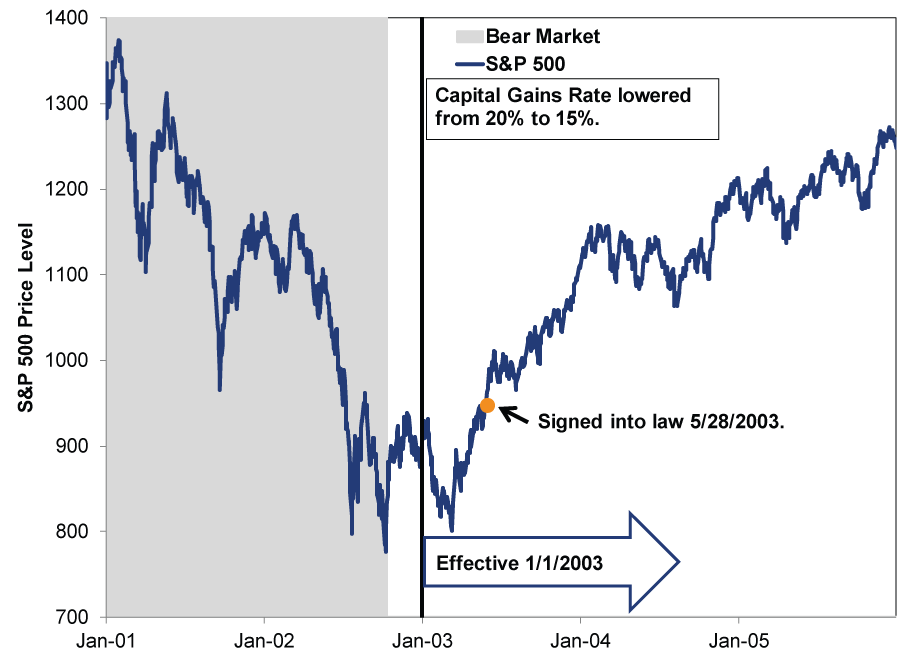

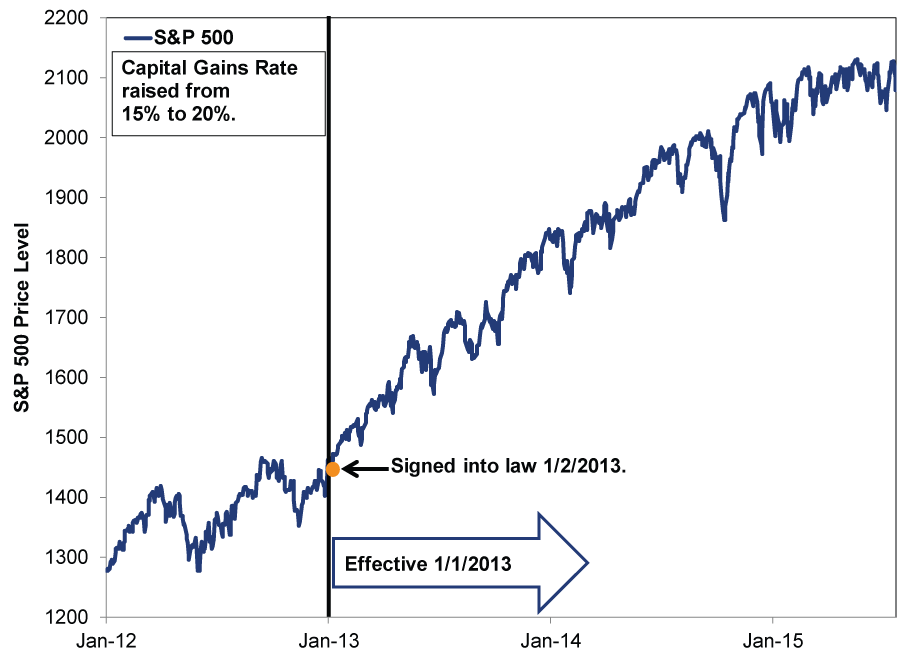

As for the other angle-whether hiking the capital gains rate could hurt stocks-we see little evidence it would. Folks often fear a hike could prompt a rush of selling to lock in gains at lower rates before the change takes effect, hurting the broader market, but history shows otherwise. Historically, the data show no conclusive evidence adjustments to the capital-gains tax rate are inherently good or bad for stocks. (Exhibit 2-6).

Exhibit 2: Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981

Source: Global Financial Data, as of 7/27/2015. S&P 500 Price Index, 1/2/1979 - 12/30/1983.

Exhibit 3: Tax Reform Act of 1986

Source: Global Financial Data, as of 7/27/2015. S&P 500 Price Index, 1/3/1984 - 12/30/1988.

Exhibit 4: Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997

Source: Global Financial Data, as of 7/27/2015. S&P 500 Price Index, 1/3/1995 - 12/31/1999.

Exhibit 5: Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003

Source: Global Financial Data, as of 7/27/2015. S&P 500 Price Index, 1/2/2001 - 12/30/2005.

Exhibit 6: American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012

Source: Global Financial Data, as of 7/27/2015. S&P 500 Price Index, 1/3/2012 - 7/24/2015.

The reason: Taxes are just one factor markets consider, and they usually aren't a big shock, either. Potential tax changes get widely discussed-sapping surprise power-and by the time a final version becomes reality, markets have already priced in the impact.

Anyway, at this point the discussion is mostly academic. Even if Clinton wins the White House (which is still way too early to handicap-more here), she'd likely need a Democratic Congress to pass this, which may be a tall order. Incumbency favors the Republicans in the House, and though the Democrats have a structural edge going into 2016's Senate races-the Republicans are defending seven Senate seats in states that voted Democratic in recent Presidential elections-they need to take a net five seats to win the majority. Doing so would require them to unseat very popular long-time Senators, which takes significant resources and near-flawless campaigning. A hypothetical President Hillary Clinton could easily have a Republican Congress, limiting the potential for big tax changes.

Campaign trail jawboning can hit sentiment in the short term, and this could impact stocks as the contest draws near and candidates try to seize momentum. But campaign pledges don't equal real policy, and it is still premature to form hard expectations for the next administration-whoever it may be. So keep an eye on developments, but also know a lot can and will change between now and November 2016. For now, however, gridlock remains, and that's what matters most for stocks today.

[i] Many times, buybacks and capex/expansion aren't funded by cash, but bonds and credit. So claiming firms can either spend their cash stockpile on buying back stock or in expansion is a false either/or.

[ii] The reasons why are debatable, but our research suggests the flatter yield curve, which reduced the supply of credit while quantitative easing persisted, bears some blame. So, we suspect, does a general risk aversion among CEOs and boards still scarred by 2008. Society seems to reward cost-cutting more than risk-taking these days.

If you would like to contact the editors responsible for this article, please message MarketMinder directly.

*The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Fisher Investments editorial staff.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

You Imagine Your Future. We Help You Get There.

Are you ready to start your journey to a better financial future?

Where Might the Market Go Next?

Confidently tackle the market’s ups and downs with independent research and analysis that tells you where we think stocks are headed—and why.