Personal Wealth Management /

Bubblicious?

Some fear markets getting too high, but bubble chatter islikely self-deflating.

It was only a matter of time. With indexes globally hitting new highs, IPOs hitting headlines nearly daily, investor sentiment surveys turning sunnier and investors seemingly returning to equity mutual funds, whispers of bubble trouble were bound to start ... bubbling. And bubble they did Monday! Sentiment is “too upbeat”! IPOs are a “danger sign”! Returning investors “could be bad”! But before you cash out and run for the hills, breathe. Evidence overwhelmingly suggests the much-hyped market froth isn’t real.

One big reason: Folks are actually talking about bubbles. Typically, bubble chatter is self-deflating. It introduces fear, which drives expectations lower, creating more wall of worry for stocks to climb. The real time to worry is when markets are soaring and bubble talk is AWOL. Like, for example, between January 1 and March 24, 2000—the tech bubble’s peak. A quick search of the New York Times archive during this window yields 45 hits for “bubble.” Most pertain to food, bubble baths, packaging and beer. One called sky-high consumer confidence a bubble, then rationalized it with observations of “the extraordinary vitality and durability of US economic growth.” (The LEI, meanwhile, was peaking.) Of the two pertaining to stocks, one claimed to identify a bubble in a single biotech stock. The other said: “This year shall be the entrance into that new era. You would be mistaken if you presumed that the rise in technology stocks are a mere bubble.” That, friends, is euphoria.

Today, investors are far from euphoric. They’re perhaps a bit happier than a month ago, amid the government shutdown, debt ceiling spectacle and fed-fueled jitters, but those signs of optimism are only mildly improved from grinding skepticism. Forward P/E ratios remain below their long-term averages and have yet to see the run-up typical of late-stage bull markets—signaling investors still don’t place an outsized premium on future earnings. Gallup’s Economic Confidence Index, which nicely captured investors’ retreat from early-2013’s budding optimism, has ticked up only a bit. The Conference Board’s and University of Michigan’s consumer confidence surveys both slipped in October. A survey from across the pond suggested long-dour Brits are finally warming up to UK stocks’ prospects, but they’re losing confidence in US markets. Perhaps the biggest, most bullish, exception is the American Association of Individual Investors’ weekly sentiment survey, but this captures a subset of investors who tend to be a sunnier, more long-term focused lot—and the survey’s emotional ups and downs have frequently led followers astray. Plus, sentiment is extraordinarily difficult to quantify—none of these gauges are terribly good. All are surveys, and all have the same weakness: They capture how folks feel at one moment in time, which could frankly be more influenced by whether they liked their breakfast than their true economic or market confidence. No survey is of much use on its own, and together they paint only a fuzzy picture.

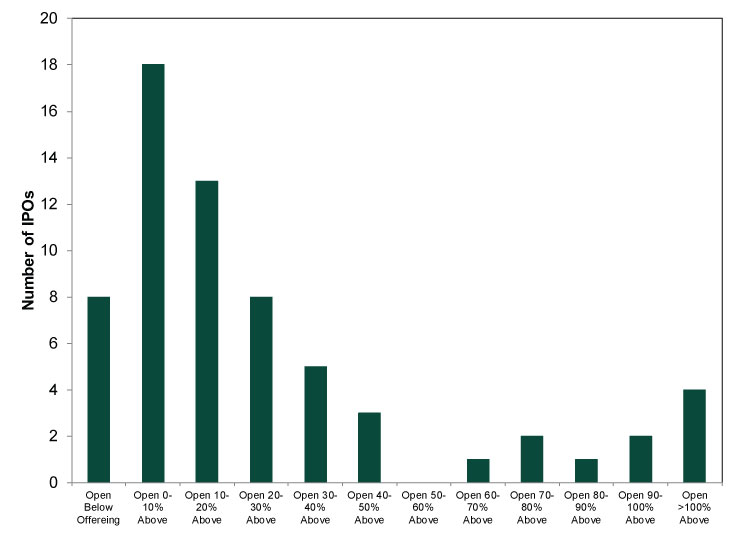

This leaves those three little letters, I, P and O. Yes, we’ve seen a fair few lately: 66 since August 1, per NYSE and NASDAQ. But NYSE and NASDAQ records show 154 firms coming to market during the tech bubble’s final three months and 24 days—over twice what we’ve seen over a similarly long period today. Then again, despite what some claim, the sheer number of new issues is largely meaningless. More telling is how prices move once the stock trades. If they don’t jump wildly higher than the offering price, that’s a good indication investors’ expectations aren’t stratospheric. Through October 23, this year’s IPOs (equal-weighted) had a mean return of 21.8%—higher than recent years, but downright tame compared to 1999’s 70.9% and 2000’s 56.4%. Yes, investors have been all atwitter—scarcely able to contain themselves—over a couple offerings in the last few days. But as shown in Exhibit 1, most new issuances are hitting the secondary market only modestly above the offering price, and a handful came in under. Of those that opened above the offering price, nearly half proceeded to fall over their first full day. Hardly something to tweet home about.

Exhibit 1: Offering vs. Opening Price for NYSE and NASDAQ IPOS, 8/1/2013-11/8/2013

Source: NYSE, NASDAQ, GoogleFinance, as of 11/11/2013.

Contrast this with the final days of the tech bubble, when new offerings regularly came in two, three, four or more times their offering price. Everybody was getting in on it! It was the new economy! Even your cabbie was trading IPOs on E*Trade. As we know now, most of this was irrational—many of these companies had shaky (at best) business models, and few turned a profit. Yet no one cared, because clicks were what mattered! As we all know now, however, this was shortsighted—many, many dot-coms failed. Of the 154 firms issued in the tech bubble’s twilight, 15 are still traded in exchanges or over the counter (not including firms like Digimarc, which went away but came back years later). Today, most everyone realizes Twitter has yet to turn a profit—the difference is investors expect it to and are willing to pay a premium to share in it. Plus, many of the names on offer are higher-quality and more stable.

IPOs’ initial performance tells us something else about investors’ mentalities: It suggests they see stocks differently than they did 14 years ago. Then, everyone was looking for the big-ticket IPO. The next Dell. The trade they could retire on. IPOs then were a get-rich quick scheme—get in early, sell out at four times the offer price and sit pretty. Today, few headlines are screaming of the opportunity to hit it big in a single swoop. It’s more about buying into the new technology or service and its potential. This is an overall healthier view—measured optimism, not irrational exuberance.

Yes, optimism. It isn’t unreasonable, in our view, to characterize a handful of hot IPOs amid a throng of ok performers as evidence investors are getting a touch more positive. But that optimism seems to be limited in scope. Onlookers see it as euphoria; others point a skeptical finger at economic growth rates or the US government’s shenanigans. Confidence usually ascends gradually, as investors slowly notice reality is better than they anticipated. Perhaps this is a nascent move back toward optimism after this year’s earlier retreat to skepticism. But either way, with reality still overwhelmingly exceeding expectations—which remain muted looking forward—this bull should have room to run.

If you would like to contact the editors responsible for this article, please message MarketMinder directly.

*The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Fisher Investments editorial staff.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

You Imagine Your Future. We Help You Get There.

Are you ready to start your journey to a better financial future?

Where Might the Market Go Next?

Confidently tackle the market’s ups and downs with independent research and analysis that tells you where we think stocks are headed—and why.