Personal Wealth Management /

Mailbag: All About the New Bank Accounting Rules

What is Current Expected Credit Loss accounting, and what does it mean for bank balance sheets—and stocks?

Earlier this week, one longtime reader sent us feedback asking a question we thought might have broader interest for our audience: Given all we have written about FAS 157’s (the mark-to-market accounting rule) role in 2008’s Global Financial Crisis, what did we think about a new rule change that just took effect? We have spent a lot of time looking at this issue but haven’t addressed it much here, mostly because accounting rules can be boring. But now that the new system is in effect, this reader’s question makes us think it is worth a public examination. In short, we think the new system could have some unintended consequences, particularly after recessions begin. But due to their size and timing, they aren’t likely to cause a bear market.

The new rule is called the Current Expected Credit Loss (CECL) accounting method. It has been in the works for about a decade and aims to fix a problem regulators thought existed during the last recession: banks’ being too slow to recognize and provision for potential loan losses. Then, Generally Accepted Accounting Practices (GAAP) required banks to provision for loan losses when they determined a loan was already impaired and likely to result in a loss. Some argued this led to banks provisioning too little, too late, leaving them on shakier footing.

CECL, finalized in 2016, is their purported solution. As Accounting Today explains, it “requires the recognition of all losses expected over the life of a financial instrument upon origination or purchase of the instrument.” In plain English, that means as soon as a bank makes a loan, it would have to provision for a potential loss, with the amount based on the borrower’s creditworthiness, current economic conditions and economic forecasts. As those variables change, banks must adjust their provisions over a loan’s lifetime.

Here, you might think, Wait! That doesn’t make sense! Why would a bank make a loan if it expects the loan to lose money? The answer, more or less, is that banks make loans when they determine the reward (revenues) exceeds the risk of loss. CECL mostly asks banks to put a dollar value on that risk and then sock money away to cover it. Whether banks think a borrower is likely to default isn’t the issue—all that matters is the mere possibility that they could. If you are now thinking, Ah, makes sense. So do banks also get to incorporate loan interest revenues into these calculations? That is an excellent question, and the answer is no. Banks will have to recognize possible losses before recording a dime of revenue, which is sort of the opposite of how it works in the real world. These rules aren’t concerned with whether the loans make economic sense for the bank. They are concerned only with building balance sheets.

Banking industry representatives and experts aren’t sold on the new rules’ benefits. You can find a good sampling of their opinions in the witness testimonies at a December 2018 House Subcommittee hearing. Many argued the rule runs counter to its aim. Regulators intended it to address the prior system’s “pro-cyclical” impact, meaning its alleged tendency to exaggerate both booms and busts. Some of the witnesses warned the new rules would instead be even more pro-cyclical, as they would encourage banks to reduce expected loan loss provisions as their economic forecast improved and ratchet up projected losses as soon recession struck. As the Chief Economist of the Bank Policy Institute explained: “For a [$250,000] mortgage loan, our results indicate a bank would be required to immediately book a loss of [$1,500] in good times for originating that loan, and nearly a [$15,000] loss in bad times for making the same loan, almost a tenfold increase. Such a requirement would undoubtedly reduce banks’ willingness to make such loans in times of stress.” In other words, credit would probably get even tighter during recessions, potentially making them worse and hampering recovery. We suspect that could limit monetary policy’s effectiveness and put more of the onus on fiscal stimulus to give demand a jumpstart.

Other concerns included compliance costs, economic forecasts’ well-documented unreliability, and banks’ likely tendency to shun less creditworthy borrowers—potentially pushing more financing into the shadow banking sector. Capital One’s CFO warned booking all losses upfront—and not recognizing future revenues—“distorts the earnings cycle of prudently underwritten loans and the economics of lending to consumers and small businesses, most significantly to those with less than perfect credit.” A longtime banking analyst estimated: “If loans can equal about 10 times each dollar of equity, that simple math amounts to $500 billion ($1/2 trillion) of potential less lending.” Accounting Today tallied up banks’ public disclosures and determined “the estimated increases to allowance of loan and lease loss reserves could range from $50 billion to $100 billion (30 to 50 percent) for about $10 trillion of applicable loans.”

That last bit is probably the biggest near-term impact. Because banks will have to apply CECL accounting to all loans on their balance sheets, they will have to take immediate one-time losses. That probably distorts US banks’ earnings this year, so we will scan Q1 earnings conference call transcripts with great interest. At the same time, we don’t expect this to be some huge market-moving event, as these accounting rules have been widely discussed for years. This isn’t like the implementation of FAS 157, when rare warnings of its pro-cyclical impact flew well under the radar. Oddly for a topic so esoteric, CECL has been financial headline fodder since 2016. That limits its surprise power. Plus, investors are generally good at seeing through stuff like this. People understand that asset quality won’t have suddenly changed—just the accounting treatment.

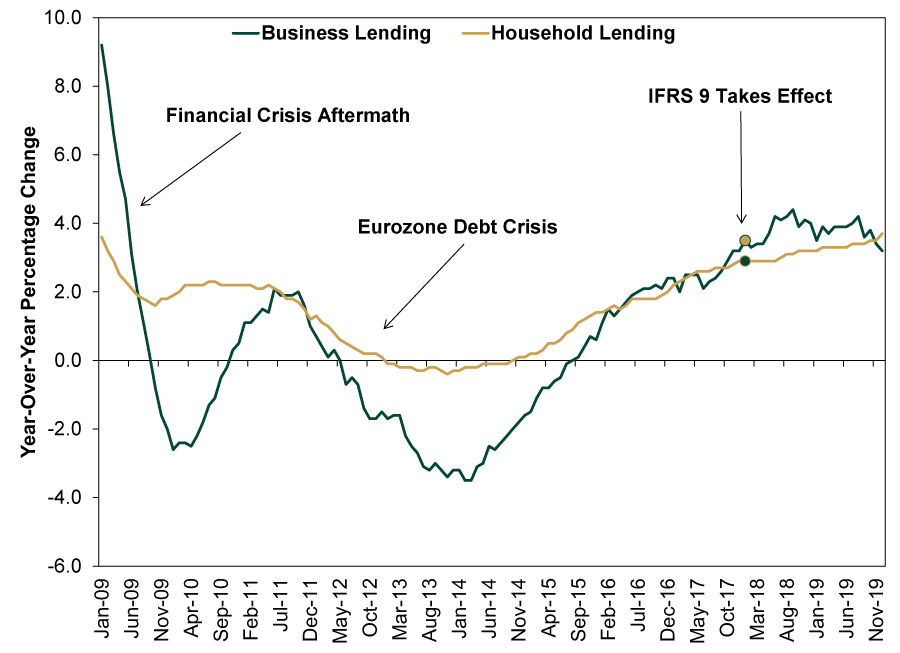

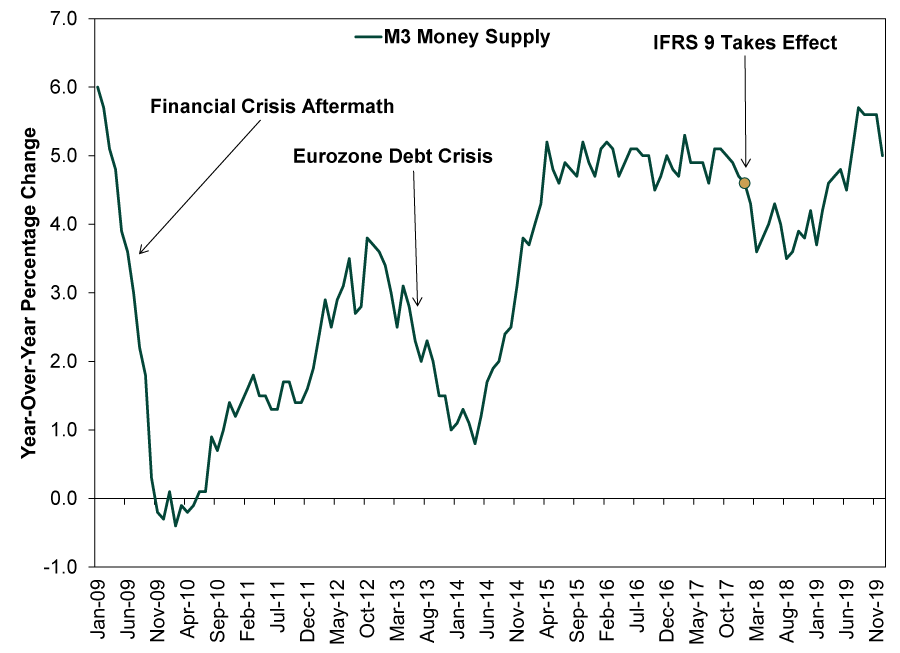

We also have evidence CECL, on its own, doesn’t cause recessions or destroy lending. Banks overseas adopted a similar ruleset, called IFRS 9, in January 2018. Since then, loan growth and M3 money supply growth have held up just fine in the eurozone. Notably, IFRS 9 didn’t wreak havoc even with negative interest rates distorting banks’ business models and flat (even temporarily inverted) yield curves weighing on loan profits. The new accounting treatment may be a small disincentive, but it clearly wasn’t a deal breaker, even with other headwinds working against banks.

Exhibit 1: Eurozone Household and Business Lending

Source: ECB, as of 1/29/2020. Adjusted loans to euro area nonfinancial corporations and households, annual growth rate, January 2009 – December 2019.

Exhibit 2: Eurozone M3 Money Supply

Source: ECB, as of 1/29/2020. Euro area M3 money supply, annual growth rate, January 2009 – December 2019.

We expect loan growth to be similarly resilient as US banks adapt to CECL. Lending is down over the past five weeks, but that is too small a sample size to read into—give it time. Banks have had years to prepare for this and have already taken action on their balance sheets to account for it—and will likely continue doing so as needed. Plus, during expansionary periods, over half of loans that default typically do so within the first year of origination. The previous GAAP standards already required banks to provision for likely credit losses over the next year. That further limits the near-term impact on bank balance sheets.

Looking further out, we suspect CECL’s unintended consequences will be most apparent after the next recession has begun. That is when the pro-cyclical downside would kick in, with banks setting aside more loan loss provisions and facing larger up-front costs when making a new loan. This isn’t great, considering credit was already tight during recessions under the old system. It could make the next bear market or recession worse than it might otherwise have been as a result. But it also doesn’t mean banks endlessly raising capital instead of lending. One, they won’t be caught off guard. Two, the Fed could flood the system with reserves, cushioning banks against the need to deleverage.

Crucially, this isn’t mark-to-market, when banks had to write all their illiquid assets down to the latest firesale price, even if they never intended to sell. It is more like mark-to-forecast. Even in recessions, most economic models don’t forecast perma-downturns. Banks can factor the likelihood of recovery into their models, giving themselves some extra wiggle room. Borrowers without top-notch credit may be shut out until the recovery gets going, but that was also the case after the financial crisis as quantitative easing flattened the yield curve. The economy and stocks still recovered.

We will keep watching this closely and updating readers as interesting data roll in. But for now, this is more of a longer-term academic issue than a near-term market-related one. If there is enough backlash from credible sources, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) could even tweak its guidance for the rule, mitigating its impact. It wouldn’t be the first time. Heck, FASB already delayed implementation for smaller banks until 2023. So watch this space, but we don’t think you ought to lose sleep over the shift to CECL walloping this bull market.

If you would like to contact the editors responsible for this article, please message MarketMinder directly.

*The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Fisher Investments editorial staff.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

You Imagine Your Future. We Help You Get There.

Are you ready to start your journey to a better financial future?

Where Might the Market Go Next?

Confidently tackle the market’s ups and downs with independent research and analysis that tells you where we think stocks are headed—and why.