Personal Wealth Management / Market Analysis

No, the Fed’s Repo Fix Isn’t QE

Don’t mistake the Fed’s means of implementing normal monetary policy for a resumption of wrongheaded “stimulus.”

Last month, an unusual thing happened in the overnight credit markets. Overnight repurchase agreement (repo) rates surged, departing from their typically tight relationship with the fed-funds target rate to hit a high near 6% intraday, before the Fed eventually intervened. Headlines went wild, calling the intervention the first since the financial crisis and offering jargon-laden explainers of this dry subject, many tinged with more than a little fear. But as we wrote at the time, this was benign—more a return to normal monetary policy that existed pre-2008 than a sign of impending doom. Now, to address volatility in short-term funding markets, the Fed has resumed expanding its holdings of Treasurys—a move some see as resuming quantitative easing (QE). Folks, in our view, it isn’t anything of the sort. Here is why.

As we noted last month, the overnight repo market is one way banks that temporarily find themselves short of required reserves can access quick funding. If daily transactions tip them below required levels (a normal thing!), they can post Treasurys they own as collateral for a loan from a big investor (think: money market fund) or bank. When the loan’s term is up, they repay and get their bonds back.

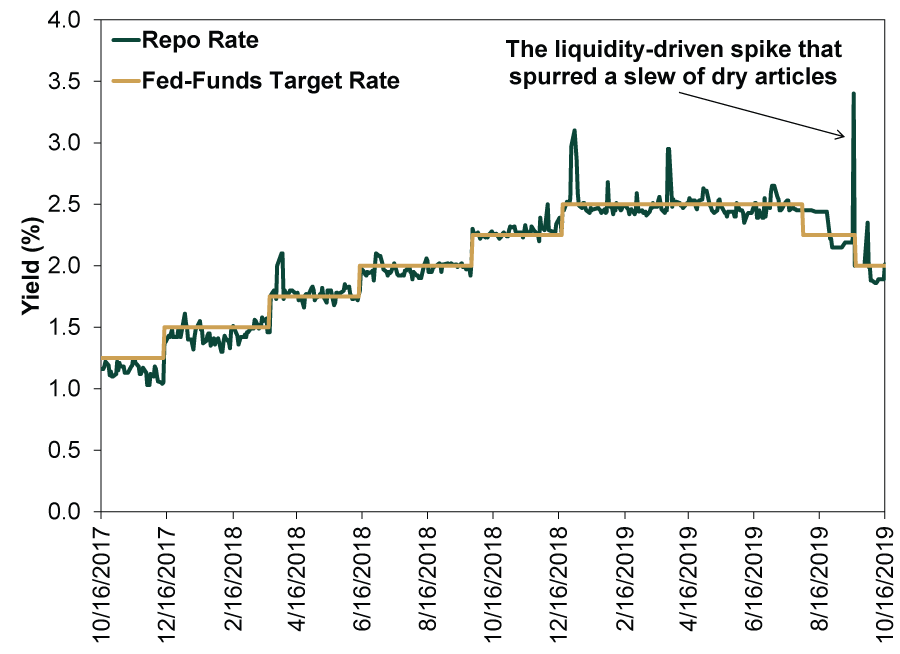

Because these loans are super short term, rates tend to track the fed-funds target rate pretty closely, except when liquidity runs tight. That happened last month due a confluence of factors: corporate tax payments draining money markets of liquidity, a Japanese bank holiday and big issuance of Treasurys. The Fed was initially slow to respond, but when they eventually did, rates fell back towards fed-funds. (Exhibit 1)

Exhibit 1: The Fed’s Day-Late Intervention Wasn’t a Dollar Short

Source: FactSet, as of 10/17/2019. US overnight repurchase agreement rate and fed-funds target rate (upper limit), 10/16/2017 – 10/16/2019.

After a series of daily moves, in early October Fed head Jerome Powell and the fun bunch over at Constitution Avenue directed the New York Fed—the branch that implements monetary policy by buying and selling bonds in the market—to take more lasting action. He directed them to buy up to $60 billion in Treasury bills daily to ensure there were ample reserves in the market. The move should increase the Fed’s balance sheet—which is what QE did. Hence, some pundits argue the two are one and the same.

But there are huge differences between this and QE. Treasury bills—which the Fed is targeting today—are by definition short term, under one year in maturity. Under QE, the Fed bought long-term bonds in an effort to lower long-term interest rates and spur loan demand. It was expressly dubbed, “unconventional monetary policy,” a way to allegedly further ease policy when short-term rates (through which the Fed normally exercises policy) were at zero percent. Further evidence of this: The Fed bought mortgage-backed securities under QE as a way to narrow the gap between long-term Treasury rates and mortgages, which was running quite wide in 2008 when QE was unveiled.

This isn’t a trivial matter. The reason, in our view, that QE was poor, disinflationary and growth-slowing policy is that by buying long-term bonds, the Fed (and other central banks) flattened the yield curve. The yield curve shows the difference between short- and long-term interest rates. Because banks borrow short term to fund long-term loans, the curve heavily influences bank lending’s profitability. Flatter curves mean less profitable lending, which likely means credit is less available, particularly to mid-tier or smaller firms.

Buying Treasury bills—as the Fed is doing under its repo fix—does none of this. It pressures short-term rates, keeping them closer to the Fed’s targeted range. It doesn’t add material downward pressure on long rates. Contrary to what many seemingly believe, long-term rates can and often do move with little relationship to short. Which makes sense! Market-set long rates usually sway based on inflation expectations. The Fed often hikes to cool inflation, driving a potential disconnect.

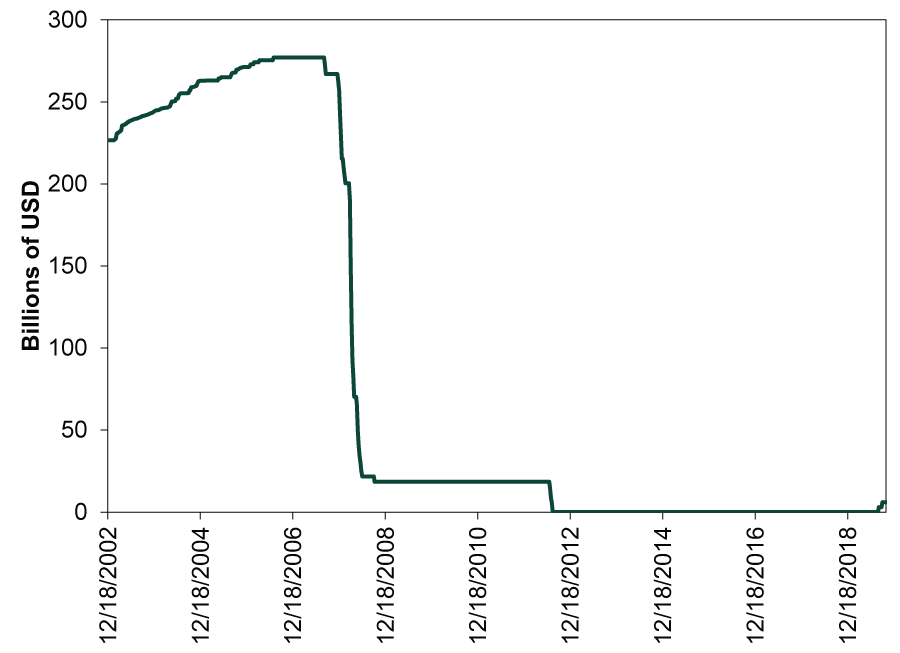

Moreover, the Fed’s buying short-term debt to implement policy within the targeted range it already announced has a name, and it isn’t QE: It is normal monetary policy. As we noted last month, the Fed may have been intervening in the repo market for the first time since the financial crisis in mid-September. But it did so routinely before QE, zero interest rate policy and the Fed’s policy of paying banks interest on excess reserves rendered that unnecessary. The Fed used to hold mountains of Treasury bills back in the day. Then they didn’t. Now they will again.

Exhibit 2: The Fed’s Holdings of US Treasury Bills

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, as of 10/17/2019. Fed holdings of US Treasury bills, 12/18/2002 – 10/16/2019.

It strikes us as emblematic of sentiment that so many pundits today confuse what the US central bank did routinely pre-crisis with a bizarre, wrongheaded crisis response tool. But we guess that is the world we live in, given the hyper-focus many have on all things Fed-related.

If you would like to contact the editors responsible for this article, please message MarketMinder directly.

*The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Fisher Investments editorial staff.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

You Imagine Your Future. We Help You Get There.

Are you ready to start your journey to a better financial future?

Where Might the Market Go Next?

Confidently tackle the market’s ups and downs with independent research and analysis that tells you where we think stocks are headed—and why.