Personal Wealth Management / Market Analysis

Reality and Repatriation

Will repatriated earnings really be a huge boost for the US economy?

Editors’ Note: MarketMinder does not recommend individual securities. The below simply illustrate a broader theme we wish to highlight.

One month after President Trump signed the tax reform bill, many claim it is already having an outsized effect. Not because consumers have more money in their pocket. Nor because some companies bragged that the corporate tax cut enabled them to pay a one-time bonus or raise starting wages a bit. Rather, a certain Tech company named after fruit announced it would invest $350 billion in America over the next five years and pay $38 billion in taxes on overseas earnings—clearly, according to tax-reform champions, a sign they are repatriating cash stockpiled overseas. While some number crunchers whipped out their calculators to see how much money could return if other overseas cash hoarders followed suit, others had visions of huge economic stimulus. Even the normally dour IMF got in on the fun, penciling in a big increase in US business investment. We cordially invite everyone to hold their horses. Not to be Debbie Downers, but when you consider how markets work (not to mention the finer points of the tax bill), it becomes clear repatriation isn’t the magic elixir folks claim. Nor should you even expect very much of it.

The popular misperception goes like this: Companies stockpiled cash overseas in order to avoid double taxation on overseas earnings, since America taxed foreign earnings only when they were repatriated. Now that the tax rate on this money drops from 35% (minus taxes paid to local governments wherever those profits were earned) to 15.5% (or 8% on illiquid assets), companies will bring all this money home and invest in new equipment, facilities, workers and R&D, unleashing a torrent of capex the likes of which we have never seen. Apple’s recent announcement is only the tip of the iceberg, they argue.

We see a glaring omission in this narrative: Companies must pay that 15.5% (or 8%) whether or not they bring the money home. Apple’s announcement wasn’t “we’re bringing a few hundred billion home and paying $38 billion in taxes on it.” It was more like, Our estimated tax bill on overseas cash, under the new law, is $38 billion, and we’re going to pay that. And we’ll spend another $312 billion here over the next five years. (Same goes for a certain clothing retailer’s similar announcement this morning.) Then, consider Apple’s “current pace of spending with domestic suppliers and manufacturers [was] an estimated $55 billion for 2018.”[i] In its last three fiscal years, Apple’s investments ranged from $45 billion to $56 billion. R&D expenses ranged from $8 billion to $11.6 billion. Factor in headcount and administrative expenses, and it isn’t clear that Apple’s big announcement deviates from whatever their plans might have been before December 22. Or that they plan to fund it with their extant cash pile, rather than future revenues.

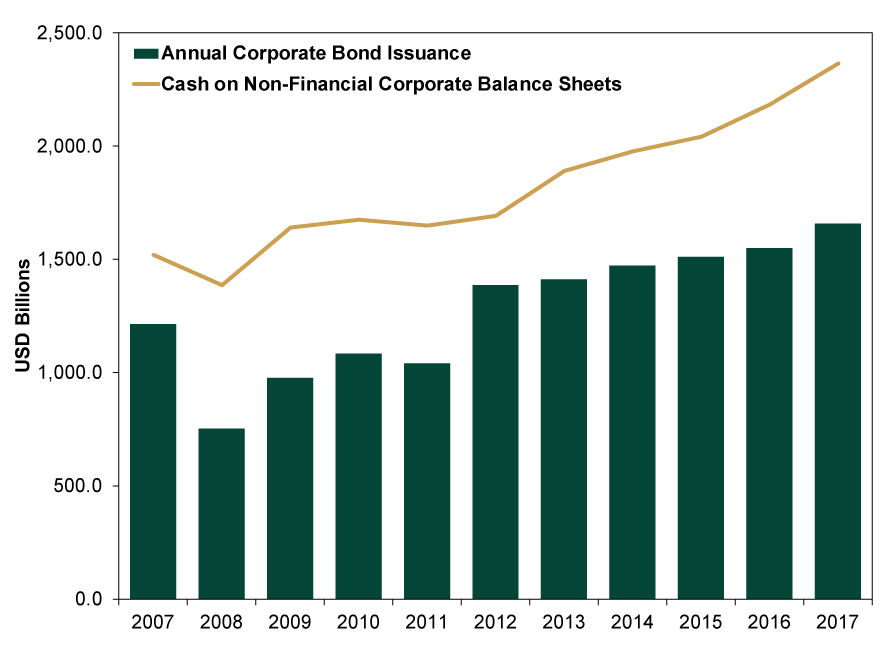

The purpose of the preceding paragraph isn’t to make points for or against Apple. Rather, it is illustrative of how easy it can be to let politicians’ marketing spin distort your view of business investment and corporate finances. We reckon there won’t be much (if any) actual repatriation. Companies weren’t just building up idle cash piles in hopes they could bring it all home one day. That isn’t smart management. Instead, they were investing abroad or finding other ways to invest in America. Huge multinationals—the kind most expect to take advantage of tax reform—are sophisticated. They are far savvier than those who write tax bills for the government, whose specialty is pandering to cherry-picked constituents, not navigating the global financial system. CFOs have long known how to skirt annoying tax barriers for years. Maybe they couldn’t transfer cash from their Irish account to their US account and start writing checks off it. But they could use that Irish cash as collateral to borrow money to invest here. We don’t think it is coincidence that corporate debt issuance rose alongside the cash on corporate balance sheets over the last decade.

It is the height of hubris for politicians in any country to think they can gate their financial systems and control money going in and out (even if they have capital controls—see Hong Kong exporters with any questions). Money, like water, typically seeps where it wants to go. Companies are always a few steps ahead of tax collectors. It just isn’t terribly good PR to say that out loud. Or to publicly bite the hand that is now purportedly feeding them. Better to play along, especially if you think you might need something from the feds in the future—like merger approvals, free trade, regulatory flexibility and building permits.

Another question most overlook: Is it even wise for companies to repatriate overseas cash and invest it all? We are a decade on from the worst financial crisis in over half a century—one that proved the value of having huge cash buffers, considering frozen credit markets played a starring role. Preferably diversified globally, just in case of liquidity crunches in some areas and volatility in foreign exchange markets. What people are calling tax avoidance could just be good old fashioned, smart financial management. We think it is sort of funny how non-financial corporations sort of did what everyone wanted banks to do—build big rainy day funds (aka countercyclical capital buffers) during an expansion—and yet no one is celebrating it.

Exhibit 1: Corporations Borrow Money, Too

Source: Federal Reserve and SIFMA, as of 1/22/2018. Annual corporate bond issuance, 2007 – 2017. Total liquid assets on nonfinancial corporate balance sheets, 2007 – Q3 2017 (all others are as of year-end).

Finally, it isn’t like the US economy has been hurting for business investment. Total US business investment is presently 16% above its pre-crisis high.[ii] It had a rough 2015 and 2016, but this was due primarily to cutbacks in the oil industry. The same goes for capital expenditures at S&P 500 firms. Cash on hand—whether from repatriated earnings or other sources—isn’t the only driver of businesses’ investment decisions. The primary consideration is the long-term return on any potential investment. If a company deems a 10-year plan sufficiently profitable, they’ll get it done whether or not they have the cash on hand.

Look, we’re bullish. We expect business investment to stay strong and for continued growth globally to power corporate earnings higher. But we also believe it is important to be bullish for the right reasons. Overestimating repatriation’s impact has the hallmarks of a road to euphoria—irrationally high expectations. Investors who can check this impulse early, in our view, have a better chance of keeping a clear head as this bull market progresses.

[i] Source: “Apple Accelerates US Investment and Job Creation,” Apple, Inc., BusinessWire, January 17, 2018. https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20180117005748/en/

[ii] Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis, as of 1/22/2018. Real private nonresidential fixed investment, Q1 2008 – Q3 2017.

If you would like to contact the editors responsible for this article, please message MarketMinder directly.

*The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Fisher Investments editorial staff.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

You Imagine Your Future. We Help You Get There.

Are you ready to start your journey to a better financial future?

Where Might the Market Go Next?

Confidently tackle the market’s ups and downs with independent research and analysis that tells you where we think stocks are headed—and why.