Personal Wealth Management / Economics

The BoE’s Monetary Bazooka is a Squirt Gun

The BoE's recent measures intended to boost growth likely won't do very much, but that's okay.

In perhaps the least surprising central bank move of all time, the Bank of England tried to blast Brexit fears with monetary stimulus Thursday. Rates cut to all-time lows! (Again!) More quantitative easing! Regulatory tweaks that don't make snappy soundbites! According to the BoE's marketing spin rationale, these measures should just barely stave off recession, which will allow central bankers to take all the credit for the UK's resilience. As for us, we're sort of disappointed, as now we'll never know how Britain's economy would have coped with Brexit on its own. But now is not the time to mourn the loss of a counterfactual. Now is the time to examine the market impact-or lack thereof-of the BoE's rescue package. It's a mixed bag overall, with some potentially helpful moves and some hindrances, but it's also small, which should limit the impact for good or ill.

After July's purchasing managers' indexes plunged-purportedly illustrating Brexit's economic impact-the BoE basically had to act. Not because the economy actually needed stimulus (we suspect it didn't, as discussed here), but because it is just not a good look for a central bank to sit on its hands at a time when many fear fallout. Lawmakers and observers have already given BoE Chief Mark Carney unkind nicknames like Britain's "unreliable boyfriend," which speaks volumes of his withering credibility. If the Bank stood pat Thursday, no one would have trusted him again. So he and his Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) cohorts passed a wide-ranging stimulus package. It cut the overnight lending rate from 0.5% to 0.25%, the lowest in its 322-year history. To ensure banks pass lower lending rates to consumers, the "Term Funding Scheme" (TFS) will let the BoE extend four-year loans to banks at around 0.25%. It restarted quantitative easing, with plans buy £60 billion of gilts and £10 billion of corporate bonds over the next six months. The Financial Policy Committee, which sets capital ratios, tweaked some rules to let banks exclude central bank reserves from their leverage ratio calculations, reducing their total risk exposure and freeing up more money for lending.

Of all of these, TFS is perhaps the most interesting. When the BoE cut rates to 0.5% in March 2009, banks took a lot of flak for not passing cheaper funding on to consumers. Banks were desperate for deposits, so in the months after the rate cut, they actually raised deposit rates. Great for savers! But not so great for borrowers. Banks aren't charities. They lend for profit. Hence, to preserve profits when deposit rates were higher, they charge higher loan rates. In central bankspeak, the transmission mechanism was broken. Later on they figured this out and created a solution, called "Funding for Lending." Accepting that banks were having trouble getting funding at overnight rates on the overnight market, the BoE and Treasury joined forces to provide that cheap funding themselves. TFS is an extension of this. As the BoE noted, it's sort of difficult for banks to pass a 0.25% deposit rate to savers without scaring them off, which would force credit to tighten. FLS and its descendants were reasonably successful, and this seems like a mostly sensible way to ensure the rate cut does what it's intended to do.

TFS isn't the only measure that makes intuitive sense. Setting aside the question of need, rate cuts are fairly traditional policy tools with over a century's worth of evidence supporting their effectiveness. Making capital requirements easier is also a time-tested tool-think of the FPC's move as a postmodern version of cutting reserve requirements, which the Fed often did to jolt the economy in the 20th century.

But QE is another matter entirely-especially the corporate bond segment. It's an attempt to solve a long-running problem in Britain's economy: businesses' (particularly small businesses') difficulty accessing credit. When traditional QE (gilt purchases) was in effect, small business lending sank, and it remains weak to this day. If you asked us, the yield curve explained why, but the BoE has a different hypothesis: They think gilt investors are less apt to take risk than corporate bond investors; hence, the proceeds from gilt purchases would go to other low-yielding, relatively low-risk assets (or, in the real world, sit on bank balance sheets). By their logic, if they buy corporate bonds, the more risk-tolerant investors they buy from will be more apt to take a flyer on a small business or startup, channeling the newly created money to its most stimulative, productive use. As an added bonus, they believe that by increasing demand for corporate debt in secondary markets, interest rates will fall, and issuance will rise.

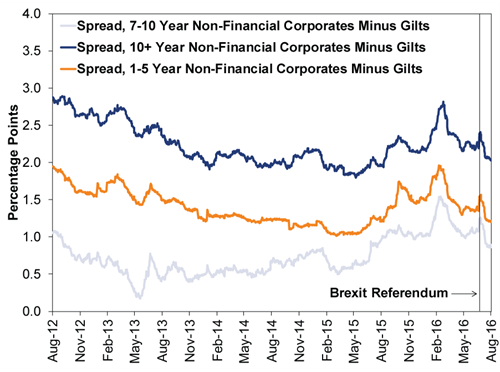

Others have noted that UK corporate credit spreads (difference between corporate and gilt yields) exceed US and euro spreads (namely, German), potentially a sign investors are wary of UK plc. But that's an oversimplified view. For one, spreads have declined significantly in the last six months-and since the Brexit vote-which suggests investors see improving risk in Britain, not a danger zone. (Exhibit 1) Plus, let's not exaggerate the geographic differences. As of 7/22, 7-10 year UK spreads exceeded US spreads by just 33 basis points. In qualitative terms, one would call that a sliver. UK high-yield spreads were actually below US high-yield spreads. There is nothing alarming here.

Exhibit 1: UK Credit Spreads

Source: FactSet, as of 8/4/2016. Spreads are the Bank of America/Merrill Lynch index yields of UK nonfinancial corporate debt minus gilts of corresponding maturity, 8/3/2012 - 8/3/2016.

It's true corporate bond issuance is weak, at an 11-year low year to date, but it's difficult to envision an extra £10 billion in demand alone moving the needle here. If issuance has been low at such low yields, there is probably something else going on. Like, maybe firms had no clarity on Brexit earlier in the year, so they held off to see how the vote would go. If issuance does improve, we suspect it would be coincidence, not causality.

As for gilt purchases, another £60 billion isn't a bazooka. More like an empty squirt gun. The BoE bought £375 billion worth of gilts from March 2009 to November 2012. During that time, the yield curve flattened, and loan growth and money supply struggled. Both were negative for long stretches. Economic growth flagged too, regularly moving in and out of contraction. Only after QE ended did the UK economy really find its footing.

Today, long rates are already well below 1%-borrowing is darned cheap for households and businesses. Demand for loans won't change much if borrowing costs fall a smidge more. But the yield curve is significantly flatter than it was during QE's first go-round. If most of that £375 billion sat on bank balance sheets, doing no stimulus, when the yield curve was steeper, why would Son of QE pack any more punch now? Seems to us like we're about to see another £60 billion in excess reserves gathering dust.

For investors, what matters is this is a very small program. The good parts aren't much to cheer and the bad parts aren't much to fear. But it lets the BoE keep up appearances without actually doing much. It's small relative to the size of the UK economy, and even smaller relative to the world. A flatter yield curve is a negative, but it would be odd for long rates to just stay where they are now. Most eurozone long-term yields fell in the run-up to the ECB's QE announcement last year, as markets priced in all the QE chatter and the rising likelihood of bond purchases. After the announcement, yields rose. Markets are forward-looking. UK yields plunged amid rampant QE chatter over the last month, and it's not unreasonable to presume they overshot, expecting a bigger QE program than the bank ultimately delivered. Plus, bond markets are global-other factors beyond BoE purchases influence gilt yields.

As for what's next, Carney and most of the MPC said another rate cut is likely. They aren't presently considering negative rates, but they are eyeing a move toward their "effective lower bound," which they consider just slightly above zero. Perhaps that looks something like the 0-0.25% fed-funds rate we had in America until last December. Or maybe they change their mind and do something different-again, unreliable boyfriend. For now, we're encouraged that they don't plan to go negative. Negative rates won't derail the economy, but the fewer there are, the better.

If you would like to contact the editors responsible for this article, please message MarketMinder directly.

*The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Fisher Investments editorial staff.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

See Our Investment Guides

The world of investing can seem like a giant maze. Fisher Investments has developed several informational and educational guides tackling a variety of investing topics.