Personal Wealth Management / Market Analysis

What Most Miss About Steel

As the UK's steel industry takes another body blow, a look at why tariffs won't help.

The Port Talbot Steel Plant. Photo by Simon Dawson/Bloomberg via Getty Images.

Since the global commodities downturn began, there is one product we haven't discussed much: steel. Energy and non-ferrous metals have hogged the spotlight. But steel has struggled, too, and with it producers in the US, UK and Europe. Wednesday, news broke that the UK's largest steel producer, Tata Steel, wrote down the value of all its British assets to "almost zero" and intends to pull out of the market as soon as it finds a buyer. About 15,000 of the UK's roughly 40,000 steelworkers hang in the balance. Britain's largest steel plant, in Port Talbot, Wales, could close within weeks. Politicians from both major parties are calling for bailouts and tariffs, fearing the demise of national steel production will threaten all of UK manufacturing. The situation in America is less dire, but Washington still slapped a 266% tariff on steel imports from China earlier this month. For global stocks, this is all mostly noise. Cold as this sounds, markets generally look past isolated, industry-specific problems and job losses. But steel is a hot political issue, and the popular narrative omits some key facts. I reckon the world would benefit from a little sunlight.

First, whatever happens with the UK's steel industry, the broader economic impact should be minimal. Plant closures would bring severe localized pain, especially in towns like Port Talbot, where the local steel plant basically is the local economy. In some areas, it would be a sad repeat of the 1980s' coal mine closures. But scale matters. Total UK steel output was just £2.2 billion in 2014-about 0.1% of GDP and 1% of manufacturing output. Only about 0.1% of the UK's 31.42 million employed people work in the industry. Even if you add in people employed at various levels of the supply chain, it's still less than half a percent of the labor market. Again, locally, it is devastating. But the UK economy is broad and diverse enough to absorb the loss.

Ordinarily, the demise of a long-declining, uncompetitive industry that employs only a few thousand people would be a footnote. But steelmaking was a huge part of British industry for ages. Like shipbuilding, it fosters an emotional attachment-hence the broad-based desire to save it. Whether or not the government bails it out or brokers a private sector rescue, the steel industry's decline will probably go down as a national tragedy that didn't have to happen. Decades of underinvestment as the industry ping-ponged between private and public ownership left its once revolutionary facilities antiquated and uncompetitive. Firms didn't take advantage of high prices when times were good to invest in new furnaces. Efforts to get more competitive instead centered on cutting costs. As a result, most UK steel plants still operate 1950s-era blast furnaces, which are less productive and more energy-intensive than modern electric arc furnaces.[i] This is especially problematic when you consider steel producers face some of Britain's highest taxes, mostly of the "green" variety. The industry is still innovating, but with prices now ultra-low due to a global supply glut and costs so high, it's all but impossible to compete.

Contrary to widespread belief, tariffs on Chinese imports won't change that. Many believe they're the golden ticket, arguing China's alleged tendency to "dump" subsidized steel at sub-market rates killed prices globally, making it impossible for developed-world producers with higher costs to compete. Tariffs on Chinese steel, they claim, would level the playing field and allow domestic producers to stay afloat-a popular theory throughout the western world.

Indeed, Chinese production soared in recent years and now accounts for over half the world's total, contributing to the massive global supply glut. China produced nearly 800 million tons of steel last year, compared to just over 10 million for the UK. And yes, most observers agree the Chinese government has subsidized unprofitable producers, seeing as how most of the industry is state-owned. But tariffs won't help. Absent from all the reporting is a simple fact: The UK doesn't import much steel from China. Neither does America, for that matter, making that 266% tariff a solution in search of a problem. Exhibits 1 and 2 give the breakdown for each country.

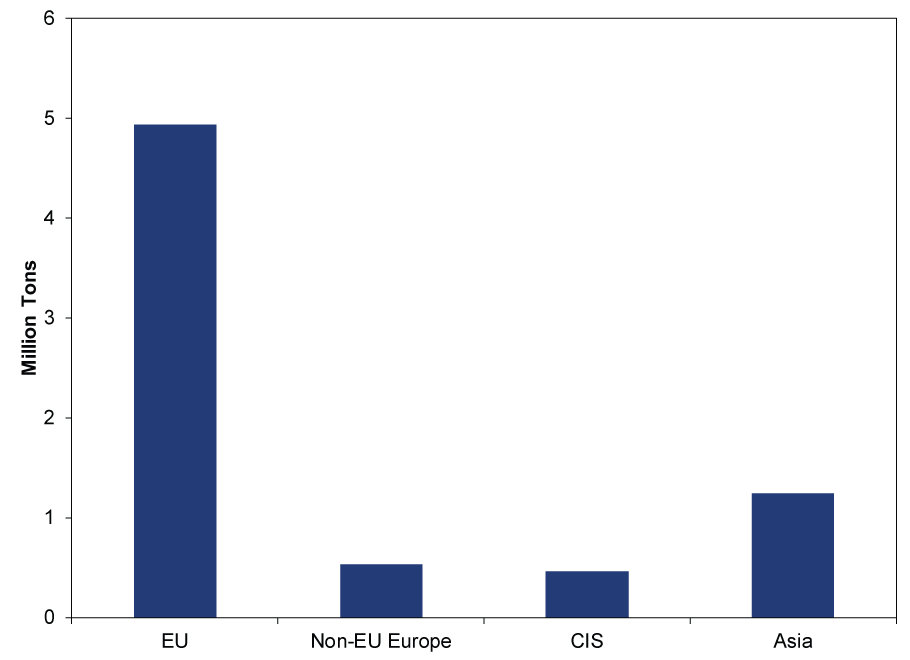

Exhibit 1: UK Steel Imports by Area of Origin, 2014

Source: International Steel Statistics Bureau, as of 3/30/2016. "CIS" refers to the Commonwealth of Independent States.

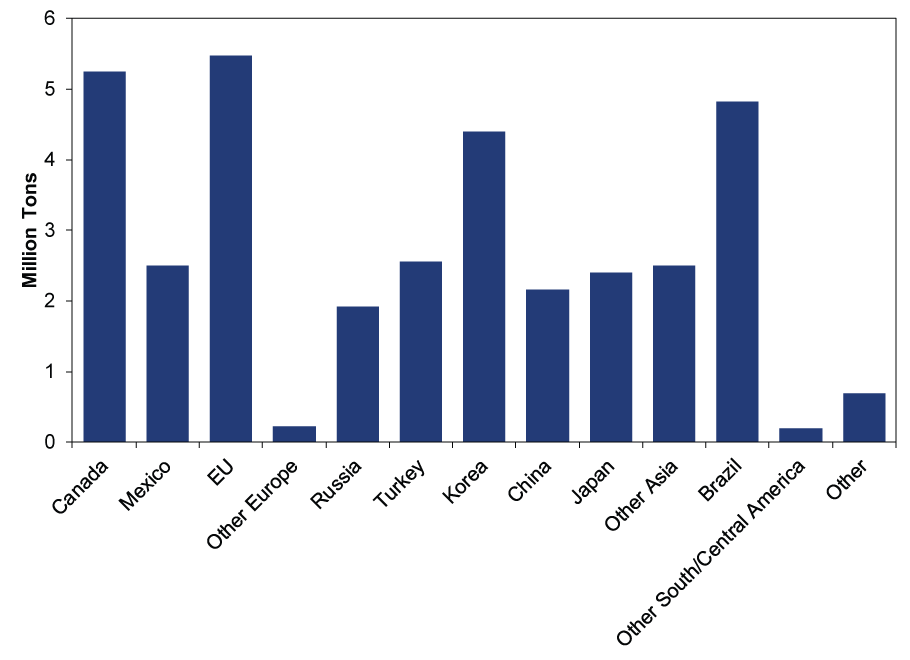

Exhibit 2: US Steel Imports by Area of Origin, 2015

Source: US Census Bureau, as of 3/31/2016.

Even in a world where protectionism actually worked[ii], it would have very little effect on China. In the messy real world, collateral damage makes it even more of a losing proposition. The UK actually runs a trade surplus in steel, and it's unrealistic to think tariffs wouldn't spark retaliation. Chinese tariffs on UK steel would arguably hurt Britain more than British tariffs on Chinese steel would hurt China. Producers are already about to take a hit from the US's new steel duties, which will be about 30% for the UK (better than 266%, but still, sorry). Any additional retaliatory tariffs would be another nail in British steel's coffin, offsetting any benefit from higher domestic prices. Sad, but true.

The same holds true at the EU level, countering claims all of Europe would be better off if the European Commission shortened the time it takes to apply anti-dumping tariffs. Of the 133.7 million tons of steel EU nations imported in 2014, only 6.2 million came from China. Most EU steel trading occurs within the union-101.3 million tons in 2014. Geography matters.

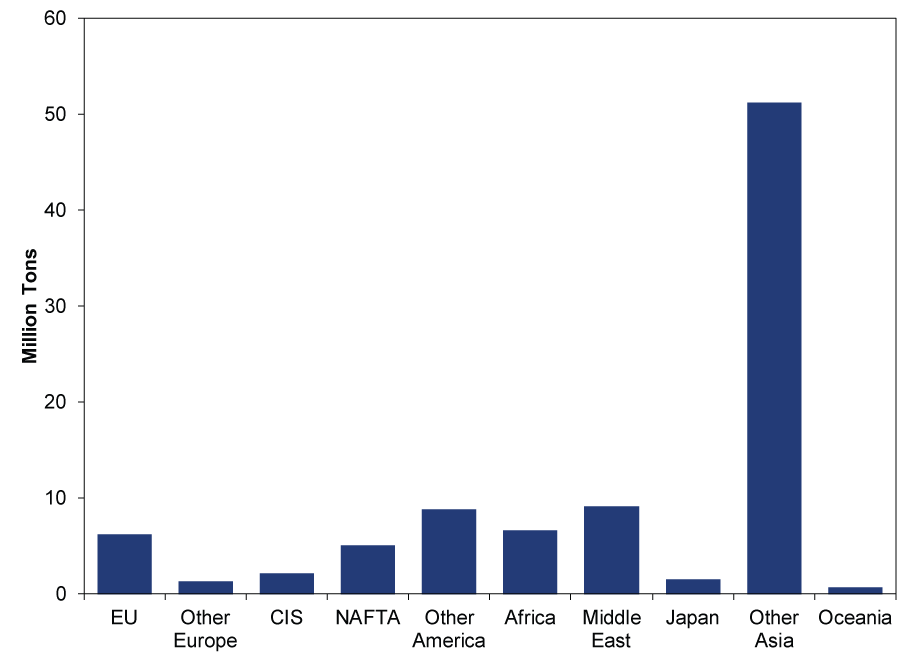

This is why Western obsession with China's purported dumping is so bizarre. Yes, China's ginormous production contributed to the global supply glut, but China isn't exactly flooding the world with steel. Of the 822 million tons China produced in 2014, only 93 million left the country.[iii] Most of it went to Asian neighbors, as Exhibit 3 shows.

Exhibit 3: China's Steel Exports by Destination, 2014

Source: World Steel Association, as of 3/31/2016. CIS still refers to the Commonwealth of Independent States. NAFTA is the US, Canada and Mexico.

Others argue this is another reason Brits should vote to leave the EU in June, arguing the UK would have more flexibility to jack up tariffs and assist the industry financially outside the union. But this, too, would be a pyrrhic victory. Britain exported over 4.3 million tons to its EU bedfellows in 2014-roughly one-third of that year's domestic production. There, too, new barriers would do much more harm than good. Regardless of EU state aid policies, free trade with very low administrative hassle has been a lifeline for UK producers.

I hate to leave this on a down note, and I won't pretend to know how the steel crisis will end. The government has effectively ruled out nationalization, preferring to broker a private sale instead. Some firms have expressed interest in Tata's UK assets, but the huge pension burden[iv] complicates any deal, and it seems highly unlikely all the plants will stay open. But there is a silver lining: Sometimes it takes a while, but there is life after plant closures. The slow death of British Coal decimated the Welsh Valleys in the 1980s, and years of pain followed. Yet now, the region is on an upswing. Advanced factories moved in, as did tech and, um, production of Doctor Who. When coal vanished, many local economies had to start from scratch. Cold comfort this might be, but with new industries already building a presence in that part of the country, it shouldn't take nearly so long for areas hurt by steel's problems to enter their next chapter.

[i] Even after a £185 million refurbishment at Port Talbot in 2013, Tata reckons it would take £2 billion in new investment to make the plant competitive.

[iii] Obviously this is a little stale, but it isn't far off the mark from 2015. Last year, China exported 100.4 million tons.

[iv] When British Steel was privatized, the pension plan stayed with it. When British Steel and the Netherlands' Koninklijke Hoogovens merged in 1999, the new company took the name Corus (and the pension). Tata bought Corus in 2007, rebranding it as Tata Steel Europe in 2011, and that's where we are today.

If you would like to contact the editors responsible for this article, please message MarketMinder directly.

*The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Fisher Investments editorial staff.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

See Our Investment Guides

The world of investing can seem like a giant maze. Fisher Investments has developed several informational and educational guides tackling a variety of investing topics.