Personal Wealth Management / Market Analysis

Black Monday After a Quarter Century

The experience I gained working on the Pacific Stock Exchange during 1987's crash went far beyond basic market ups and downs. And it's as poignant today as it was 25 years ago.

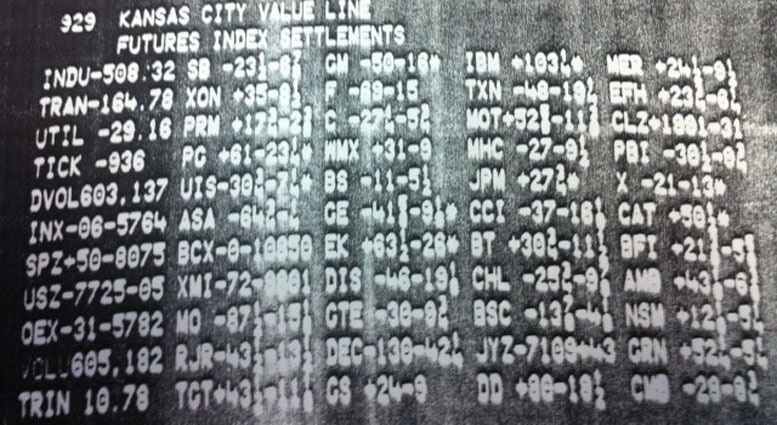

A photocopy of my computer monitor from October 19, 1987. Source: Author.

Black Monday, October 19, 1987, conjures one thought for the average investor: market crash. For me, it means much more: an unforgettable and indescribable fright, fear of the unknown and a timely and valuable life lesson. At the time, I was a 35 year-old father of two and a Specialist on the now-defunct Pacific Stock Exchange, responsible for maintaining fair and orderly markets in over 50 individual securities, all also traded on the NYSE. (Please note: This function is entirely different from working with individual investors or as a Registered Investment Adviser.)

Broad markets had done quite well in 1987 through August, when the S&P 500 peaked late in the month. From there, a more gradual decline (relative to what would follow in October) ensued-though quietly enough it didn't get much attention then in the press and is largely forgotten today. Instead, what's replaced the broader understanding of a bear market that began in August and ended in December 1987, is a focus on the events of one particularly negative day.

The market opened on Monday, October 19 with extreme sell-side imbalances. The influx was across the board. With few buy orders to offset the large number of sellers, it became apparent opening indications would need to be much lower to attract potential buyers.

Markets were instantly volatile, with any rebound attempts quickly quashed in another wave of selling. Actual news was replaced by unsubstantiated rumors, their seriousness increasing each time: the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) may halt trading; the NYSE may halt trading; the SEC may halt trading; banks are refusing to extend credit to Wall Street; FOREX transactions are being rejected. With each story, the pace of incoming sell orders mounted.

Confusion turned to pandemonium. I only had to time to react, not strategize or think. All I was confident of was the major American companies I knew so intimately were declining in value by 25%-40%. But was that based on fundamentals, or was it purely sentiment? Pandemonium morphed into dread.

The final hour of trading on Black Monday saw a cascade of sell orders, most generated through program trading and portfolio insurance-related sell programs. Bid/ask quotes, normally around 12.5 cents apart, spread to a dollar or more, as specialists were forced to be the only buyer, and their available capital was rapidly depleting.

The closing bell brought no relief. I sat in stunned disbelief, unaware of the damage done, unaware I hadn't visited the restroom for six hours, unaware of how much stock I had accumulated and totally clueless as to how much money I had made or lost. The trading floor quieted from a screaming cacophony of frenzied traders and ringing phones to an eerie silence.

Calculating the day's results was not pleasant. Losses in Gannet alone were large. United Technologies losses were a bit less. Warner Lambert actually had a small profit. But Exxon, my most traded stock, showed unimaginable losses. And the vast majority of the other 46 securities I traded had losses.

I typically left the Exchange soon after the closing bell, around 1:30 PM on the West Coast, which allowed me to get home to my sons. That day, I did not leave until almost 5 PM. Stepping from the mausoleum-like aura of the floor, buried a foot deep in discarded trade tickets, into the San Francisco autumn day's soft sunshine and warmth felt surreal. People were driving cars, walking around and talking on corners-all seemed normal. "What was wrong with them?" I thought. "Don't they know the American financial system just crumbled? Don't they care?"

As I rode the subway home, a thought struck me: How do I tell my wife? How do I look at my sons, whose future I just lost? How do I walk into a home I will soon be evicted from? Utter despair hit me like a boot to the gut. Everything seemed to drop out from under me, and I was alone in a crowded commuter train, bound for a car I would have to sell, a town I would have to leave, a home I had likely lost and a family I had let down.

Feeling faint, my head spinning, but knowing I had to face my family, I walked into the kitchen. There, my wife quickly pecked me on the cheek and said, "You're late ... I'm late ... Watch the boys ... Dinner is on the stove..." and was out the door. Apparently, she didn't know I had just ruined her life.

I saw my sons, ages six and three, on the back lawn and went out to greet them. Seeing me, they charged, tackling my legs. "Wrestle! Wrestle!" Still wearing a coat and tie, I took a stance. I had my eyes gouged, my ears bit, my hair pulled and was generally abused, as only two young boys can do.

And something suddenly changed. At first, I couldn't identify what or why-but I felt strangely satisfied. My dread had vanished. Confusion was receding. The dark curtain was lifting and light flooding in. Suddenly, it was clear: My life's wealth was not on a trading floor or in some brokerage account. It was not my home, my cars or any other possession. My true, undeniable wealth was right there, twisting my nose and stuffing lawn trimmings down my shirt.

And did I wrestle. I chased those kids, threw them in the air, bit their ears, pulled their hair and twisted their noses. We ate dinner and made brownies. We played games and watched cartoons. We laughed and celebrated the irreplaceable wealth of family.

My wife returned several hours later. "What is this about the stock market's crashing?" I smiled. "Ah, it was nothing...."

Tuesday morning I was on the Exchange floor at 5 AM. Traders were quiet, serious and focused. With some luck, a strong opening would let me jettison inventory, reduce my capital and comply with my loan covenants. Incoming orders were mixed-a relief from the previous day's sell-order avalanche. As the opening approached, it was clear buyers outnumbered sellers significantly, and stocks were indicated significantly higher, allowing an opportunity to sell inventory at higher prices.

But as stocks opened, rumors began anew. Buy orders vanished, and a torrent of sell orders hit all stocks. An orderly opening quickly descended into another chaotic selling frenzy, overwhelming specialists' abilities and capital. Trading in numerous well-known stocks was halted, and the CME halted S&P futures trading, choking liquidity further and spurring the flood of sell orders.

As trading resumed, the Federal Reserve reiterated a previous statement:

The Federal Reserve, consistent with responsibilities as the nation's central bank, affirmed today its readiness to serve as a source of liquidity to support the economic and financial system.

And as if on cue, major American corporations began announcing stock buyback programs to support their faltering shares. The mood swing was almost instantaneous: Selling abated, and a rush of buyers stormed markets.

Prices exploded higher, and the buyers kept coming. What looked like Terrible Tuesday was now Terrific Tuesday. Markets, which had earlier been down, surged to close the day up more than 5%.[i] The following day, markets were up even more, and they finished the week up more than 10%[ii] from Black Monday's close. Emotionally exhausted and mentally drained, there was little in the way of celebration at the end of the day. The immediate gratification was survival. Capital markets had been stressed but functioned. Where panic had temporarily dominated, cooler heads prevailed and were rewarded.

Markets finished 1987 up about 5% from the October 19 close, and 23 months later, the S&P 500 hit new all-time highs.[iii] Realistically, very few folks could see the longer term-even among professionals-instead of focusing on the (admittedly large) near-term volatility. And I clearly recall feeling like all hope was lost for my family's future. But realistically, as we look back from a perch 25 years removed, it's clear the wrong path would've been to act on those emotions and close up shop. That, in fact, would've jeopardized my goals and my family's living standards much more.

Today, it seems as though there are many whose confidence has been dinged by the events of 2008-2009. But the valuable lesson I learned during a wild week on Wall Street is to make sure you don't lose sight of your long-term goals. Allocating to avoid volatility may subject you to the far greater risk you lose your lifestyle through lower returns.

[i] S&P 500 Price Level Returns.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] S&P 500 Price Level Returns. High prior to 10/19/1987 was 336.77 reached on 08/25/1987. This was exceeded on 07/26/1989.

If you would like to contact the editors responsible for this article, please message MarketMinder directly.

*The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Fisher Investments editorial staff.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

You Imagine Your Future. We Help You Get There.

Are you ready to start your journey to a better financial future?

Where Might the Market Go Next?

Confidently tackle the market’s ups and downs with independent research and analysis that tells you where we think stocks are headed—and why.