Personal Wealth Management / Market Analysis

Italy Doesn’t Look to Be Going Greek

Equating Italy to Greece seems like a sign of overly dour sentiment.

Since late September, Italy and the EU have been at loggerheads over the former’s budget proposal. Last week, the European Commission (EC) said it would begin the disciplinary process over what it argues is an excessive deficit target of 2.4% of GDP.[i] The EC claims Italy’s government is “sleepwalking into instability.” While rumors of waffling abound, Rome publicly rejects the EU’s interpretation, arguing its spending plan is necessary for sustainable growth. This budget drama has inspired analogies to another high-debt euro nation’s odyssey: Greece. Some worry much-larger Italy’s treading down a Grecian path spells trouble for the eurozone—and global markets. However, in our view, this comparison misses the mark and signals how dour eurozone sentiment is today—a reason to be bullish.

Greece and Italy share some similarities—and not just because they are lovely coastal Mediterranean nations with good wine, olive groves and problems with tax evasion. Both have populist-led governments that antagonized the EU during their campaigns and early days in office. Before Italy’s Five Star Movement (M5S) and League were battling Brussels, Greek firebrand Alexis Tsipras and his far-left Syriza party sparred with the EU over bailout terms. Both countries also carry a lot of debt relative to GDP: Greece’s debt-to-GDP ratio of 179.7% tops the eurozone.[ii] The second highest? Italy’s 133.1%.[iii]

Greek debt proved problematic starting in 2009, after the government revealed it had massively underreported deficits. Greek sovereign debt yields spiked, requiring an EU/IMF/ECB bailout—and two defaults. But despite the fears and drama, Greece never crashed out of the eurozone. By Greece’s third bailout, many were aware it lacked heft to cause major economic pain—Grexit or no. However, Italy is the eurozone’s third-largest economy. Should Rome go the way of Athens, some worry the country would be too big to bail out—allegedly a reason to fret Italy’s budget.

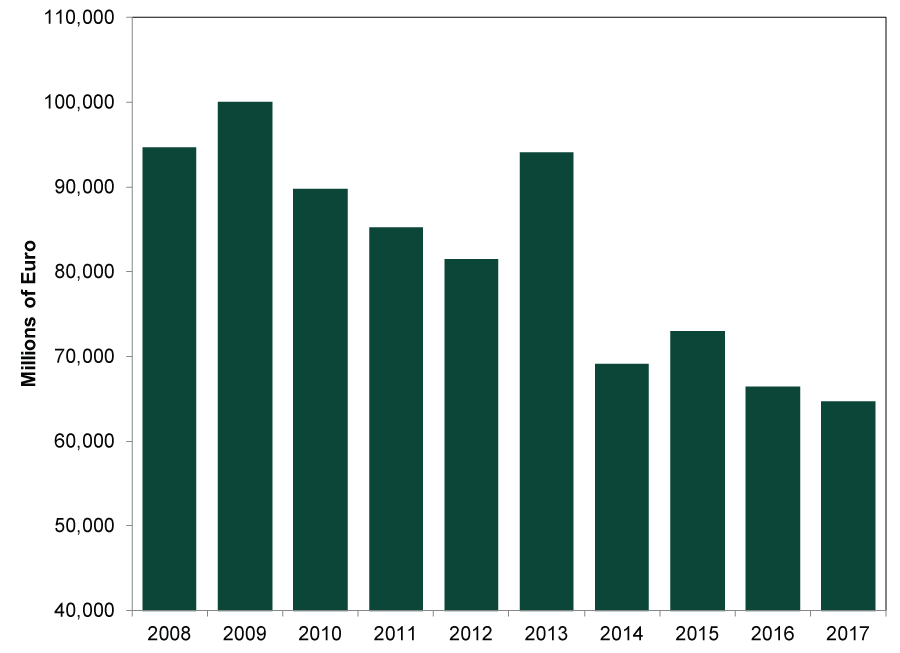

However, Italy is far from turning Greek. For one, Greece’s economy spent much of the past decade in recession. From 2008 – 2016, GDP contracted -27.1%,[iv] and though the economic recovery started last year, Greece has a long—looooong—way to go. If you use GDP as a loose proxy for economic activity and the general tax base, declining government revenue isn’t surprising. (Exhibit 1) Less revenue complicates debt obligations, contributing to economic difficulties.

Exhibit 1: Annual Greek Central Government Revenue, 2008 - 2017

Source: Eurostat, as of 11/13/2018. Total government revenue for Greece, annual, 2008 – 2017.

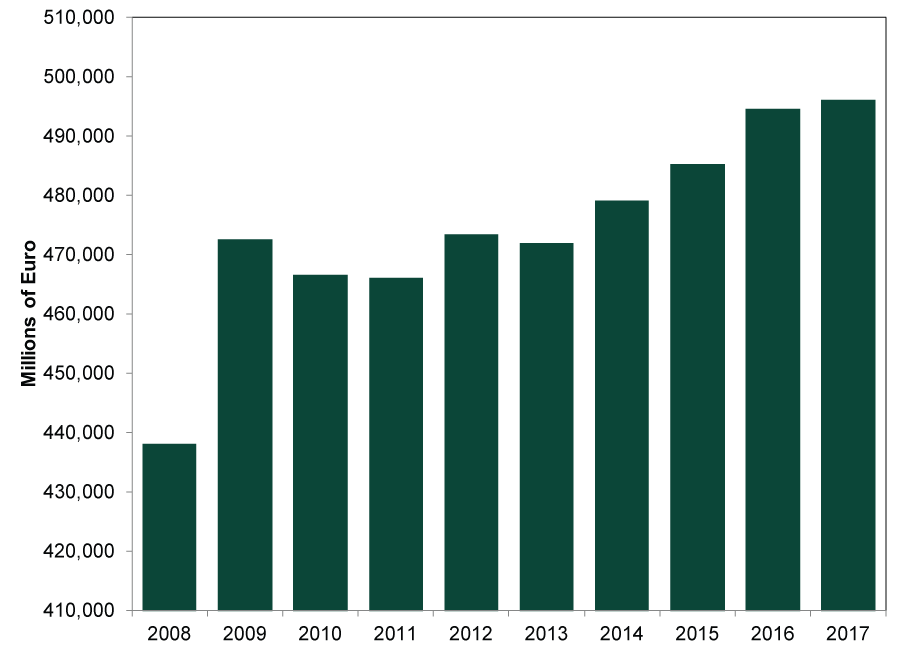

Contrast that with Italy. From 2009’s economic trough through 2017, Italian GDP grew 9.7%—not gangbusters, but not contractionary.[v] GDP surpassed its pre-crisis peak in 2015 and has been plodding along since. Growing Italian central government revenue reflects this. (Exhibit 2)

Exhibit 2: Annual Italian Central Government Revenue, 2008 – 2017

Source: Eurostat, as of 11/13/2018. Total government revenue for Italy, annual, 2008 – 2017.

As for debt-to-GDP, a high ratio doesn’t mean economic trouble looms. A country’s ability to make interest payments matters more, and this isn’t a major issue for Italy right now. As we discussed in our July commentary, “What Italy’s Recent Bond Auction Reveals About Debt Fears”:

Debt interest payments’ share of tax revenue is 14%—the lowest in decades. This topped 40% in the 1990s, a strong period for Italy’s economy and stock market. We think it is hard to argue Italy is uniquely burdened now. The Italian Treasury also extended its average debt maturity to seven years from three in the 1990s, locking in low rates. As a result, rates would have to rise much higher and stay there to be a problem. Rates are half what they were seven years ago—and they didn’t cripple then.

Politically, Greece shows a populist-led government isn’t necessarily as extreme as perceived. In 2015, Tsipras and his motley Syriza crew were the euro bad boys. They resolved not to tolerate the EU’s and IMF’s bullying, even holding a referendum over whether to accept the EU’s bailout terms. Voters, rallied by Tsipras, said no—yet Tsipras made the mother of all political U-turns, compromised and accepted the EU’s terms for a third bailout. He has remained PM since then, leading privatization efforts and behaving like establishment eurozone politicians. He even went as far as counseling the Italian government to give up the deficit fight this week.

This doesn’t mean Italy’s populists will also compromise and moderate. However, fears of M5S and the League bringing market-roiling chaos seem a tad overwrought. While these parties share the “populist” moniker, they have contrasting political ideologies. The League is a far-right, anti-immigrant party while M5S is a diverse hodgepodge of anarchists, socialists and antiestablishment types that skews left politically. Even Syriza, rife with internal acrimony, was more unified than Italy’s coalition. Little ideological common ground makes it difficult to reach consensus—necessary to pass major legislation.

For all the antiestablishment chatter, populist politicians are still politicians. They follow the political winds and moderate when necessary to retain power. Right now, Italian voters have little desire to exit the euro—aka a “Quitaly”—and M5S and the League have updated their anti-euro language accordingly. Plus, not all “populist” ideas are necessarily market negatives. The coalition’s tax reform plan calls for two tax rates (of 15% and 20%). Many economists argue flatter, simpler taxes could reduce Italy’s long-running tax avoidance issue—a positive.

In our view, worst-case scenarios about Italy’s debt drama—to the point of making Greece comparisons—signal how dour eurozone sentiment is. Italy isn’t Greece. The eurozone at large—especially its economy—is faring better than most seem to appreciate. That disconnect between sentiment and reality is reason to be bullish, especially on the eurozone, in our view.

[i] This is below the eurozone’s 3% of GDP deficit limit. However, Italy’s debt breaches the eurozone’s 60% limit, subjecting it to added scrutiny.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Ibid. Annual GDP in current prices, 2008 – 2016.

[v] Ibid. Annual GDP in current prices, 2009 – 2017.

If you would like to contact the editors responsible for this article, please message MarketMinder directly.

*The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Fisher Investments editorial staff.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

You Imagine Your Future. We Help You Get There.

Are you ready to start your journey to a better financial future?

Where Might the Market Go Next?

Confidently tackle the market’s ups and downs with independent research and analysis that tells you where we think stocks are headed—and why.