Personal Wealth Management / Market Analysis

Should Bond Holders Expect Poor Long-Term Returns?

What fixed income investors should weigh when considering rising interest rates.

A few months ago, 10-year Treasury yields hit an all-time low of 1.36%, as investors piled into Treasury bonds in the wake of the Brexit vote.[i] Since then, Donald Trump's win and expectations for higher inflation have sent yields up 70 basis points (0.70%).[ii] As rates have risen, so have fears about the end of the alleged 35-year bond bull market-and the possibility of a bond bear market, should rates climb higher. Since bond prices and interest rates move inversely, many seemingly fret higher rates mean bonds are doomed to poor long-term returns-arguing bondholders should ditch them post-haste. In our view, this overlooks important nuances suggesting the case for investors who need fixed income exposure hasn't changed.

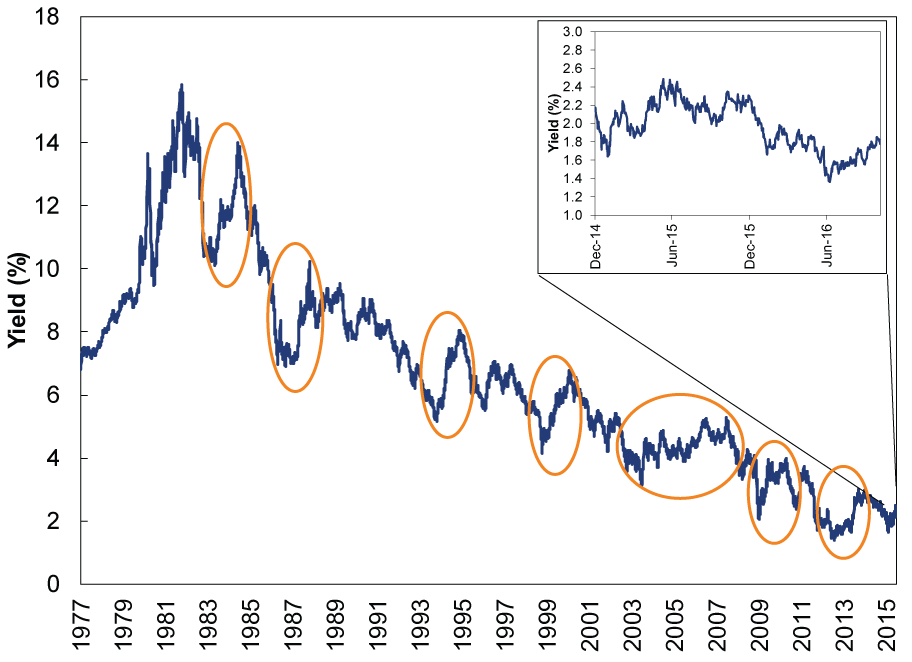

First, let's look at the last 35-ish years of yields-that long-term bond bull. Fast-rising inflation and aggressive Fed rate hikes pushed 10-year yields to 15.84% in 1981. But after the Volcker Fed put inflation in check, rates began a secular move downward to recent lows. However, this wasn't a straight line down.

As Exhibit 1 shows, bond yields went through several cycles where yields increased. Since 10-year US Treasury yields peaked in September 1981, rolling 12-month yields rose 35% of the time.[iii] Even if yields do experience a long-term climb, odds are investors will see plenty of periods where yields fall. Having an actively managed fixed income strategy can help take advantage of these opportunities.

Exhibit 1: 10-Year US Treasury Yields

Source: FactSet, as of 11/4/2016. 1/1/1977 - 11/4/2016.

Investors should also be wary of the notion interest rates will rise materially from current levels in the next 12-18 months. For one, there is no magic long-term average interest rate bond yields move towards-mean reversion isn't real in investing, and that includes bond yields. Sure, the Federal Reserve and economists everywhere like to speculate about where rates should be depending on a number of variables, but these predictions are theoretical constructs-moving targets that change with the data.

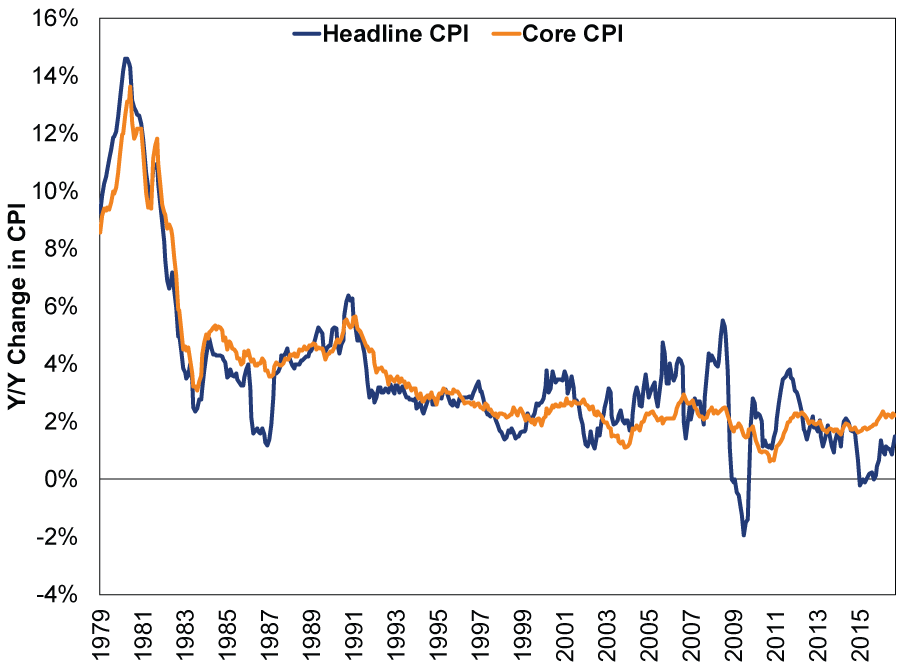

Among the key data points investors should watch are inflation expectations. When these increase, investors demand higher bond yields as compensation for future cash flows' declining purchasing power. Lately we've seen inflation expectations perk up, tied to energy and health care prices. As we wrote last month, energy prices can be very volatile and plunging oil prices in mid-2014 detracted from headline inflation, but that impact has diminished in recent months. Looking to the next few months, it's easy to make a case for year-over-year headline inflation accelerating as energy price comparisons look back to the early 2016 lows. Core inflation (stripping out volatile food and energy prices), currently higher than headline inflation, remains the stabler of the two measures, and the one investors should pay more attention to.

Exhibit 2: Headline and Core Inflation

Source: FactSet, as of 11/7/16.

Among core inflation components, services prices have gradually climbed while goods decreased, helping stabilize core inflation, which ranged between 1.6% and 2.3% over the past five years. (See Exhibit 3 for more detail.) Health care costs have been core inflation's biggest driver recently and are expected to rise more as 2017 starts, but this doesn't mean inflation will jump materially. Some point to the potential for inflation as President-elect Trump pushes Congress to ramp up infrastructure and defense spending. However, this isn't a foregone conclusion-it may be hard for him to do. And if he does, it is unlikely increased spending will flow through to higher inflation in the next 12 - 18 months. More likely, inflation trends back towards the longer-term average of 3.0%. Late-1970s' style inflation is extremely unlikely.

Exhibit 3: Components of Consumer Price Index

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, FactSet, as of 11/4/16. (HT: Luke Puetz)

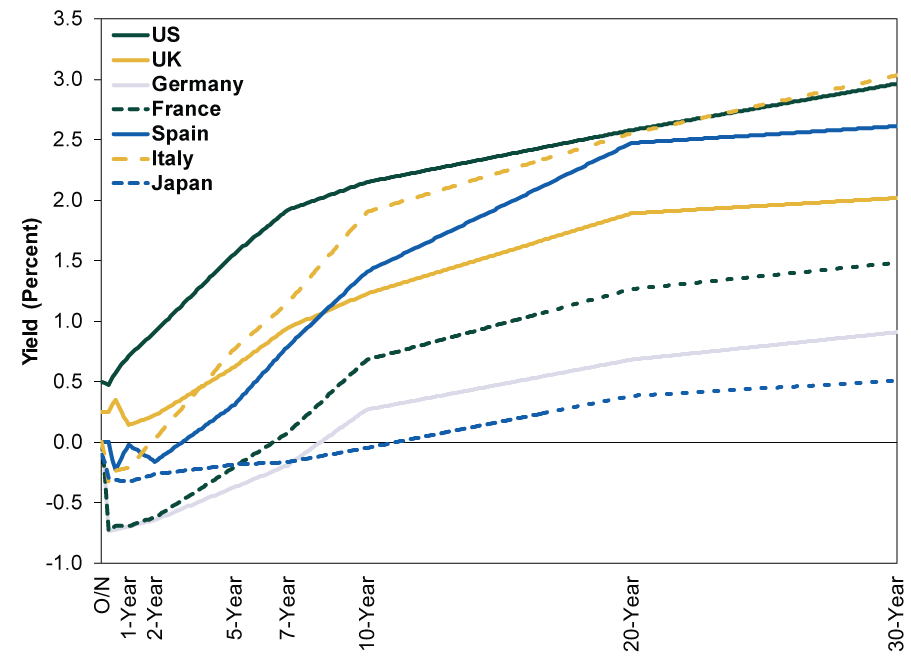

Beyond persistent low inflation, global factors should weigh on rates. US interest rates are unlikely to move materially higher in the next 12 - 18 months while so many developed world sovereign yields are negative or very low. Large pensions and institutional investors are generally indifferent between sovereign bonds from the US, Japan, UK or Germany. If one country's yields rise, demand for its bonds increases, counteracting the effect. Expecting US bond yields to rise materially while the eurozone and Japan continue their quantitative easing and negative interest rate policies overlooks this.

Exhibit 4: Developed World Bond Yields

Source: FactSet, as of 11/11/2016. Yield Curves on 11/10/2016.

Longer term, interest rates could rise to levels last seen before the 2008 global financial crisis. Continued economic growth (or a sudden epiphany by central bankers) should eventually bring the end of inefficient QE programs. Sentiment towards equities might improve, reducing demand for bonds. Or maybe a combination of some or all these helps push rates up. What then? Should investors give up on bonds for the next decade or so to hedge this risk?

We don't think so. In rising rate environments, bond investors need to carefully balance interest rate risk (aka duration) and yield in their portfolios. Duration measures a bond or bond fund's price sensitivity to an immediate one percentage point move in interest rates. For example, a bond with a 5-year duration would see its price move up or down by 5 percent if its yield moved down or up by 1 percentage point. Typically, longer-maturity bonds have a higher duration and higher yields than shorter-maturity bonds with the same credit rating. If you expect rising rates, you can try to reduce interest-rate risk by tilting towards lower duration bond types. Blending different types of bonds (corporates/Treasurys/municipals) also helps manage the duration and yield tradeoff within a portfolio.

If inflation does become a larger concern, several types of bonds offer inflation-adjusted yields. Moreover, as interest rates rise, active bond investors have the ability to reinvest interest payments into higher-yielding bonds, increasing portfolio yield. Shunning bonds isn't necessary or really even desirable. Some bonds are, at times, negatively correlated to stocks, meaning they can mitigate equity volatility. And, for many investors, bonds will continue to play an important role in portfolios by providing higher cash flows and lower short-term volatility than stocks. Going forward, if bonds are appropriate for your situation now, they likely will be even if rates rise some. That may require a more disciplined yet active approach, but it doesn't mean you should bail on bonds in case rates rise.

If you would like to contact the editors responsible for this article, please message MarketMinder directly.

*The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Fisher Investments editorial staff.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

You Imagine Your Future. We Help You Get There.

Are you ready to start your journey to a better financial future?

Where Might the Market Go Next?

Confidently tackle the market’s ups and downs with independent research and analysis that tells you where we think stocks are headed—and why.