Personal Wealth Management / Market Analysis

The ECB’s ‘Strategy Review’ Yields Little New

A microscopic shift to an inflation target the ECB rarely hit likely won’t change much.

Hailed as a big shift last Thursday, the ECB concluded its 18-month strategy review seeking more effective monetary policy. Emerging from the shift? A “new” twist on inflation targeting and a loose plan to help fight climate change. But if you tune down the noise to look at reality, we think you will see the new strategy is pretty hard to distinguish from the old.

The chief change to the ECB’s target inflation rate appears almost imperceptible. Instead of “close to, but below” 2% y/y, now it is a “symmetric” 2% target.[i] According to the ECB’s announcement, this means deviations above and below 2% are “equally undesirable.” That may be, but markets are more interested in what the central bank would do about them. Many pundits assumed the ECB would tolerate above-target inflation for a while if it was below before, like the Fed’s new inflation targeting approach. Not so. As German Bundesbank head Jens Weidmann—1 of 25 members on the ECB’s Governing Council—noted, the new strategy doesn’t try to make up for past misses. The lauded “new strategy” simply gives policymakers theoretical cover for trying to lift inflation toward the 2% y/y target, should it fall below that mark. The differences between this and the “extraordinary monetary policy” of the last seven-ish years when inflation ran sub-target seems pretty semantic to us.

In our view, that verbal cover underscores the ECB’s inability to hit its target. This isn’t a knock on the ECB specifically—there is no evidence any central bank can reliably hit inflation goals. On this score, the ECB is in the same boat as the Fed, Bank of England and Bank of Japan. Despite their extraordinary efforts and proclamations, all have mostly undershot their inflation targets after installing them.

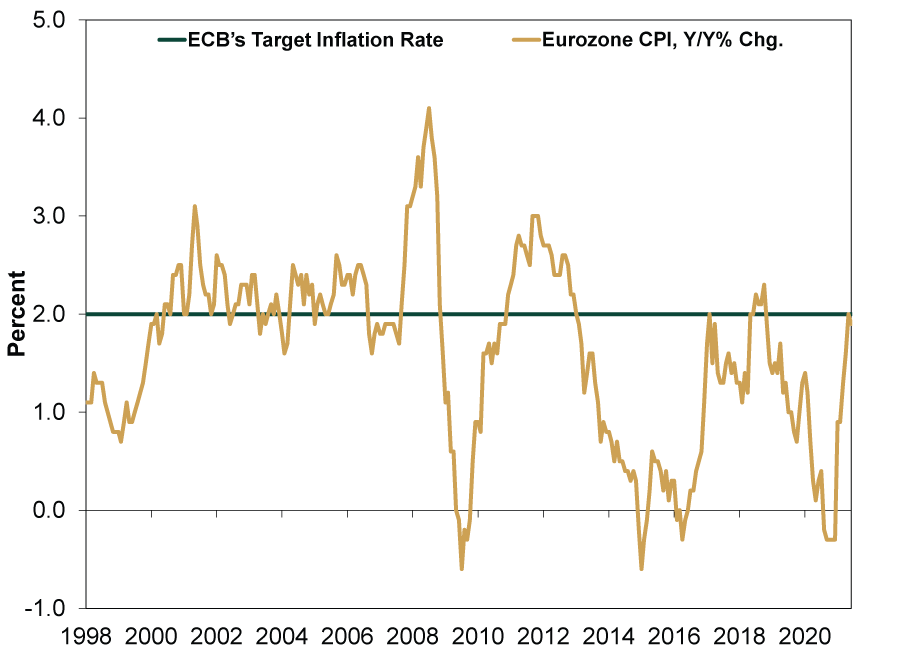

Since the Fed set its inflation target in 2012, there have been only a few months when its chosen gauge—the personal consumption expenditures price index—has hit it. It came closest in 2018, when it hovered within a couple tenths of a percentage point of 2% for most of the year.[ii] But mostly it has been far off. Similarly, UK, Japanese and eurozone central banks haven’t been close. Exhibit 1 shows the results of the ECB’s efforts. While it struggled to keep inflation “close to, but below” 2% y/y, mostly overshooting in the decade following its inception, the ECB woefully undershot its target over the next decade plus.

Exhibit 1: The ECB’s “Control” Over Inflation Is Spotty

Source: FactSet, as of 7/12/2021. Harmonized Consumer Price Index, January 1998 – June 2021.

Now, there is little doubt central banks have influence over inflation, which is, after all, a monetary phenomenon. But the degree of precision implied by these targets—and the verbiage changes around them—is irrational. Inflation is driven by too much money changing too few goods and services. Money supply measures? Fallible. Velocity measures—which aim to tally how fast money changes hands economy-wide—are even less perfect. The idea a central bank understands these factors and can forecast where they are heading well enough to boost or lower inflation by fractions of a percentage point makes no sense. The ECB’s ostensible strategy shift doesn’t make it any more capable of controlling inflation. It also doesn’t clear up the central bank’s decision making any—it may do “whatever it takes,” but not predictably.[iii]

As for the ECB’s climate change policies, it has committed to “include climate change considerations in its monetary policy framework.” Chiefly, this presently means the ECB will require companies issuing bonds to make climate change risk disclosures for them to be eligible as collateral or for quantitative easing (QE) asset purchases. Perhaps they eventually exclude big polluters from purchase. But for now, that isn’t the case. Nor is it an enormous issue, considering the ECB’s QE program overwhelmingly targets government bonds. It is also possible this move politicizes ECB policy, but that doesn’t seem like an issue in the here and now, either. Ditto for adding climate risk to bank stress tests, another new policy—stress tests were already opaque and arbitrary, and this doesn’t change that.

For investors, we think the ECB’s new strategy should be dealt with the same way as before: Wait and assess the implications of its actions after the fact. Attempting to figure them out beforehand is futile—and unnecessary, in our view. Monetary policy hits with a lag and markets, which incorporate all widely available information—including expectations for central bank policy moves—near instantaneously, have no preset reaction to it anyway.

[i] We won’t blame you if you fail to see the significance!

[ii] Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, as of 7/13/2021. Statement based on PCE price index, year-over-year percent change, January 2018 – December 2018.

[iii] “Verbatim of the remarks made by Mario Draghi,” Mario Draghi, ECB, 7/26/2012.

If you would like to contact the editors responsible for this article, please message MarketMinder directly.

*The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Fisher Investments editorial staff.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

You Imagine Your Future. We Help You Get There.

Are you ready to start your journey to a better financial future?

Where Might the Market Go Next?

Confidently tackle the market’s ups and downs with independent research and analysis that tells you where we think stocks are headed—and why.