Personal Wealth Management / Market Analysis

A Q&A on China's (Semi-) Command Economy

China isn’t likely to sacrifice growth in the name of inflation fighting. Here’s why.

In the past year, every time China released an economic statistic or adjusted monetary policy, simultaneous concerns of “too hot” growth or “too cool” policy arose. Make no mistake: China needs strong growth and low inflation to keep its authoritarian government in power (just look at Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya) and won’t intentionally jeopardize either. Here are some answers to commonly asked questions about China’s economic balancing act.

For two decades, China’s annual economic growth rate has not fallen below 7%. How has China grown so fast?

China’s growth has made it the world’s second largest economy. The secret to its success is its economic and government structure, which allowed for dramatic industrialization tied to heavy infrastructure investments. In other words, China has chosen to maximize labor productivity gains at all costs, including sacrificing capital productivity.

The authoritarian government owns most (often estimated at roughly two-thirds) of the country’s assets and capital, including all of the land and major banks. Therefore, land and funding are always available for any new public infrastructure project.

Funding is also abnormally cheap because of China’s (purposefully) undervalued currency, strict capital controls (Chinese citizens can’t invest outside China), limited social safety nets (such as social security, health care, or unemployment benefits), and a very limited bond market. This encourages high savings rates and helps funnel those savings into deposits at state banks, which pay artificially low rates due to limited investment alternatives. Combined with access to land, it’s the perfect combination for an infrastructure boom! (Though less great for a free press.)

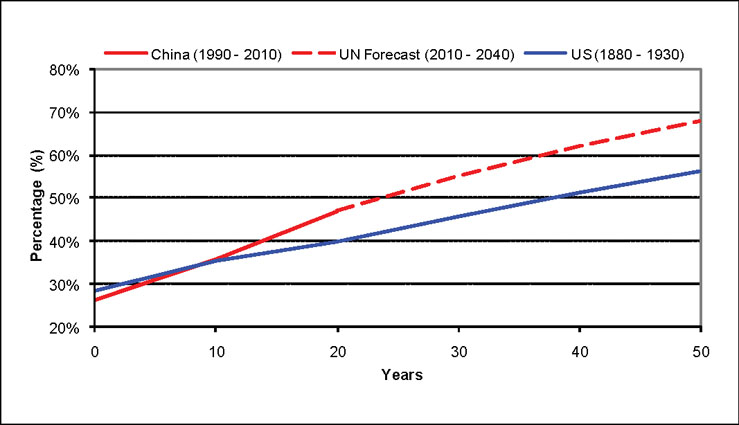

And what a boom it’s been. Productivity gains from infrastructure and industrialization have launched China’s economic rise. Over the last decade, China has invested approximately 9% of GDP annually in infrastructure—roughly double any other major country. As seen in Exhibit 1, this has driven massive urbanization—47% of the population is now urbanized vs. 26% in 1990. And, much like US industrialization in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, tremendous productivity gains have led to rising living standards (although the US took many more years to urbanize than China).

Exhibit 1: China vs. US Urbanization Rates

Source: UN and US Census Bureau.

Are there downsides to China’s model?

Yes. In addition to the obvious, societal drawbacks to communism, there are a number of major downsides, most notably inefficient capital allocation and a limited ability to control inflation. In addition, steady, low-inflation economic growth is required to appease the rapidly urbanizing population.

Inefficient Capital Allocation

As many intuitively know, governmental allocation of capital is nearly always less efficient than the private sector’s. In China, heavy-handed control of the major banks has meant many bad loans, in turn necessitating recapitalization of China’s entire banking system after periods of national economic stress (1999, 2003, and 2010, with total estimated costs of $650 billion).

From the government’s perspective, these bailouts were worth the cost because the loans that necessitated them fostered productivity gains from industrialization and infrastructure that dwarfed the negative effects of poor capital allocation. Due to diminishing returns on additional infrastructure (a village’s first road brings many incremental benefits, but the 100th may add very little), at some point, China must modernize its economic system or increasingly struggle under its inherent inefficiencies.

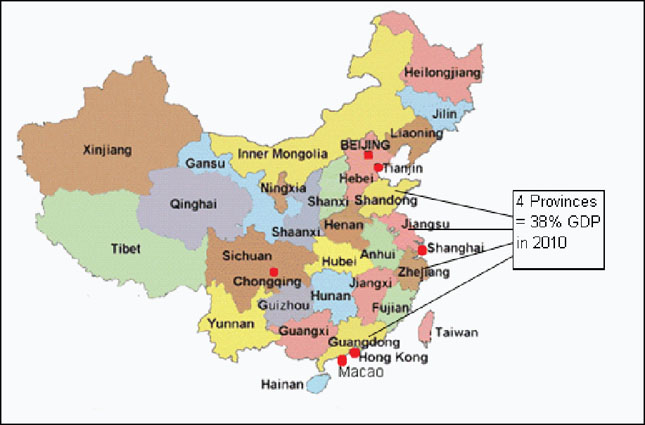

However, that struggle hasn’t yet arrived. With over half its population still rural and development highly concentrated on the coasts, China will continue to benefit from infrastructure developments. Out of 31 provinces, 62% of 2010 GDP came from the 10 coastal provinces—with 4 provinces contributing 38%. While recently impressive, China’s urbanization rate is still only equivalent to the US around 1915.

Exhibit 2: China GDP by Leading Provinces

Source: National Bureau of Statistics China, maps-of-china.net.

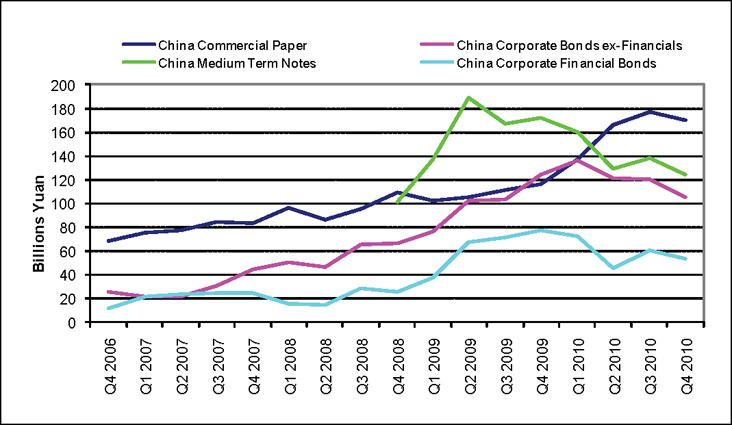

Although the day of reckoning for China’s current economic model is not here yet, China sees it coming and has begun to address some of its financial system inefficiencies. This includes developing a local bond market (Exhibit 3), increasing private banking sector competition, reducing capital controls, expanding international usage of its currency, and introducing pro-consumption policies. For example, in the past year, China announced plans to start a municipal bond market, allowed limited competition from Taiwanese banks, permitted greater yuan usage in trade, allowed qualified foreign banks to reinvest yuan within China, created a futures market, and significantly increased minimum wages, government pension payouts, and healthcare spending. And they’re just getting started.

Exhibit 3: China Bond Issuances (4 quarter average)

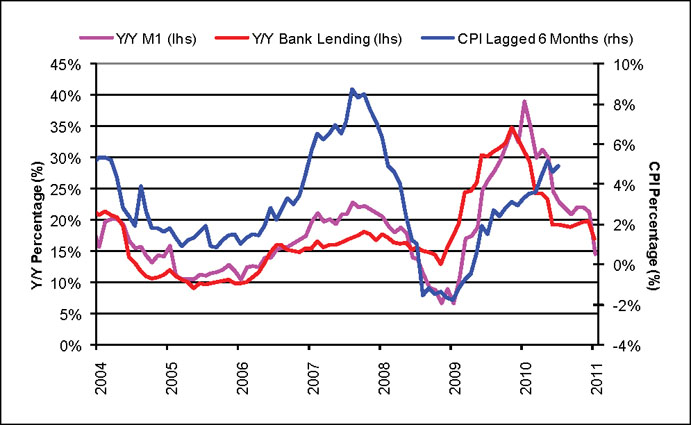

Free capital flows, fixed exchange rates, and discretionary monetary policy are often called the impossible trinity—you can’t have all three. As part of its plan to support exports and create an infrastructure boom, China chose to restrict capital flows and control its exchange and interest rates. But because of trade, foreign direct investment, and other investment, China can’t restrict all capital flows and therefore can’t fully control its monetary system and inflation. Thus, China has historically struggled with inflation despite raising interest rates and reserve requirements, and occasionally even allowing its currency to appreciate. Ultimately, crude loan quotas have proven the most successful at controlling inflation and money supply (see Exhibit 4).

Exhibit 4: China Money Supply and Inflation vs. Loan Growth

Source: Thomson Reuters.

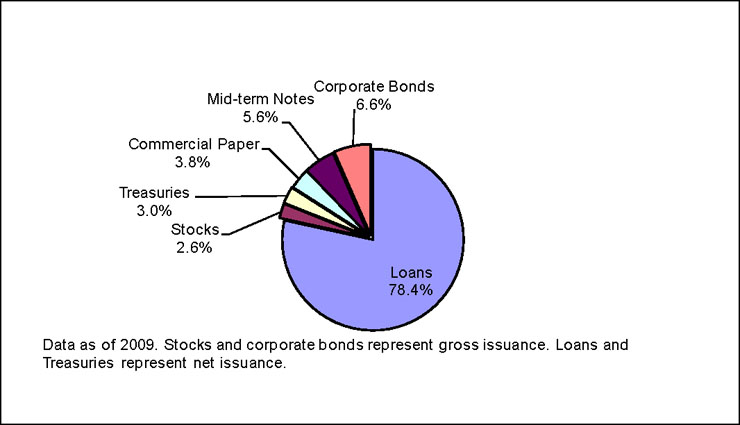

These quotas are workable largely because of China’s underdeveloped bond market, which makes firms dependent on bank loans for funding (see Exhibit 5).

Exhibit 5: Chinese Business Funding Sources

Sources: Bloomberg and Thomson Reuters.

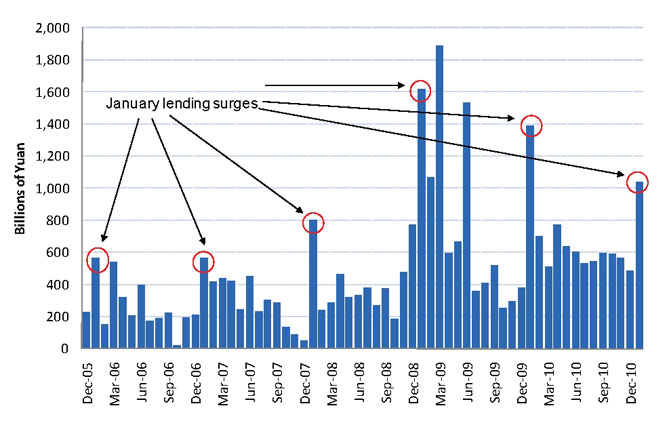

China tends to set loan quotas annually. In effect, this limits year-end lending as quotas are reached—only to see lending surge when a new year resets them (see Exhibit 6).

Exhibit 6: China New Yuan Loans

Source: Thomson Reuters.

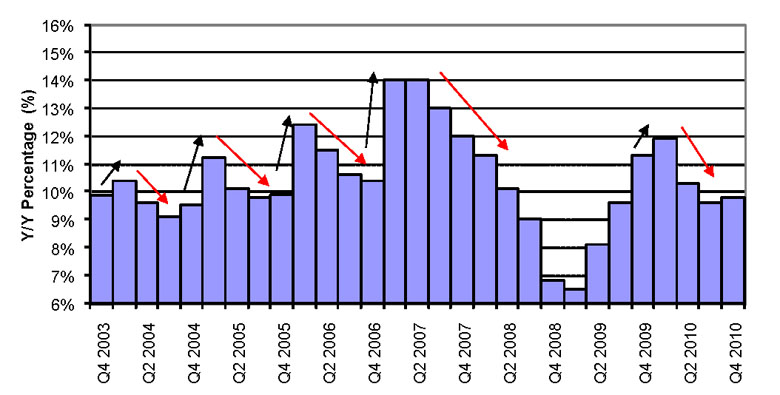

Unsurprisingly, this credit surge contributes to GDP spikes early in the year and deceleration in later quarters (see Exhibit 7).

Exhibit 7: China GDP Surges in Q1 on Annual Loan Quotas

Source: Thomson Reuters.

Steady, low-inflation economic growth for government stability

With the Soviet Union’s collapse, Emerging Markets governments saw capitalist economies provided greater stability and wealth. Hence, they increasingly embraced capitalism to reduce deficits, control inflation, and industrialize. While many adopted relatively democratic governments, China retained its communist structure. Thus, the population lacks the political rights to effect peaceful change—increasing the probability of violent dissent or revolution. Since the push for change generally increases during economic downturns as living standards are pressured, China’s leaders are keen to avoid recession or hyperinflation. Of the two, China is likely to tolerate slightly higher inflation as opposed to slower economic growth given the consequences for the general populace. This is one reason current fears of excessive inflation-fighting seem misplaced.

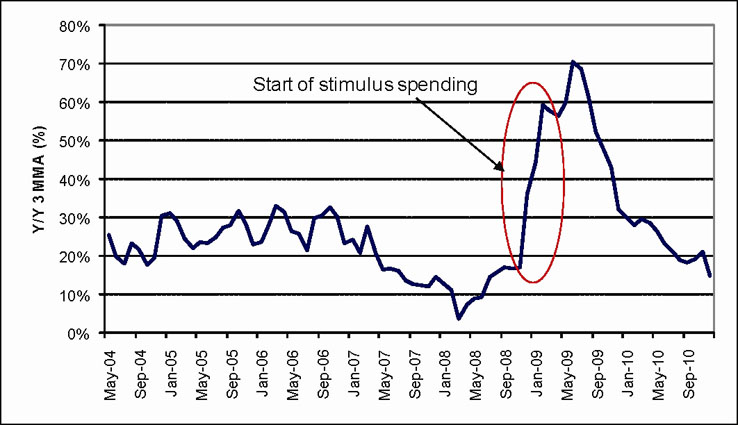

Over the last two decades, China has avoided such events. But as gains from infrastructure projects diminish, China will inevitably face the boom-and-bust cycles of capitalism—and many question how China’s governmental structure will fare then. But as previously discussed, that seems a longer-term issue. At the moment, its gains from infrastructure remain large enough to avoid recessions through extremely high levels of state-directed bank lending and infrastructure spending, like we saw during the recent recession (Exhibit 8).

Exhibit 8: China Infrastructure Growth (roads, rail, waterway and ports, air transport, pipelines, post, and telecom)

Source: Thomson Reuters.

Since 2009’s rapid rise in state-directed lending, China has been balancing its need for economic growth with gradually decreasing loan growth. In an attempt to contain money supply and inflation while only slightly decelerating growth rates, the government announced a 2011 loan quota of 7.2 trillion yuan (approximately 15% loan growth y/y, a reduction from 2010’s 19% growth y/y). But historically, banks haven’t strictly adhered to the government’s quotas. In 2010, banks blew through the 7.5 trillion yuan quota, lending 7.95 trillion yuan. To avoid the limit, many banks also pushed loans off their balance sheets, removing them from official statistics.

Seeing this, the government has taken additional steps for 2011: Banks have been directed to bring 25% of off-balance sheet assets back on the books per quarter. The government also stated bank reserve requirements will now be based on “differentiated reserve requirements”—limits determined monthly on a case-by-case basis contingent on which portions of the economy the bank lends to (and other metrics). This likely grants the central bank more control over bank lending and money supply but also increases government interference in capital allocation—exacerbating the aforementioned inefficiencies.

Lower loan growth levels and stricter compliance with quotas should help China continue balancing inflation and economic growth. But as previously discussed, even if inflation does rise, China would likely tolerate that over an economic slowdown.

Is China’s real estate in a bubble?

Many investors have read about uninhabited “ghost towns” China built to purportedly sustain economic growth and fear that growth strategy is unsustainable. There is the interesting case of the Inner Mongolian ghost town, Kangbashi. However, the city currently has no hospitals, schools, television, or Internet services, so potential residents’ hesitancy to move is understandable. In fact, the city exists for a unique reason: The region’s main city (Ordos city) is running out of water, and the government plans to relocate everyone to Kangbashi.

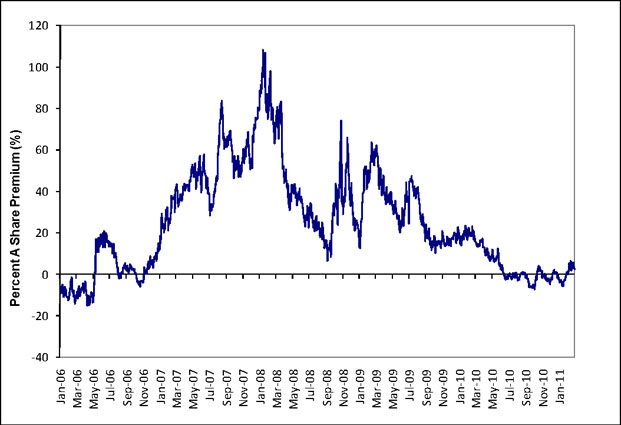

China has built infrastructure aplenty that has failed to provide an adequate return on investment. But this is outweighed by gains elsewhere. It’s the average gain in productivity that matters most. Moreover, while it’s true that China’s real estate valuations are lofty by international standards, so are valuations of virtually all China’s investable assets. Strict capital controls give Chinese investors few alternatives. For example, the same company’s shares in China’s domestic stock market (A shares) often trade at significant premiums to those listed in Hong Kong (H shares). (See Exhibit 9.) Furthermore, with inflation running above bank deposit rates (negative real returns) and no nationwide property tax, Chinese investors often park cash in real estate.

Exhibit 9: China A vs. H Share Premium (measured by Hang Seng AH Index)

Source: Thomson Reuters.

As long as China’s government limits its citizens’ investment options, Chinese real estate valuations are likely sustainable. However, China has attempted to limit price appreciation to maintain the affordable housing urbanization requires. It also helps prepare the country for the inevitable day it relaxes capital controls (as discussed above).

If China’s economy is unlikely to tank, should I be heavily in their stock market?

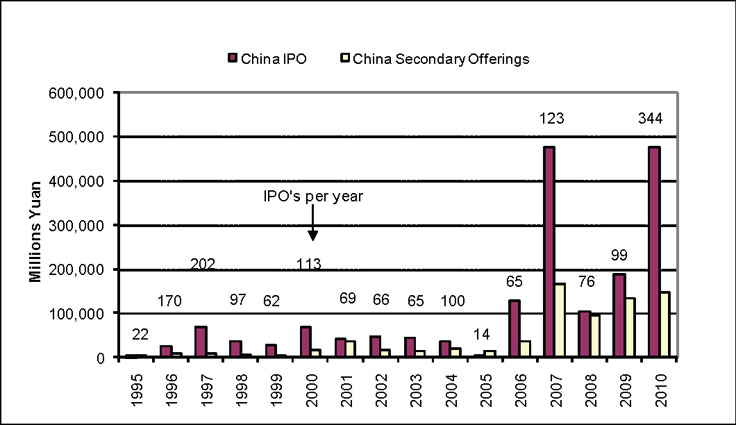

Not necessarily. Economic growth and stock market results are two very different things. While China’s economy should maintain a healthy growth rate in 2011, history shows decelerating loan growth typically does not bode well for China relative to Emerging Markets peers. Furthermore, a Chinese IPO boom is rapidly increasing equity supply—a potential headwind for Chinese stocks. (See Exhibit 10.) Select firms and industries present attractive investing opportunities in China, but 2011 might not be a year of stellar returns for the broad Chinese market.

Exhibit 10: China Equity Offerings

Source: Bloomberg.

If you would like to contact the editors responsible for this article, please message MarketMinder directly.

*The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Fisher Investments editorial staff.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

You Imagine Your Future. We Help You Get There.

Are you ready to start your journey to a better financial future?

Where Might the Market Go Next?

Confidently tackle the market’s ups and downs with independent research and analysis that tells you where we think stocks are headed—and why.