Personal Wealth Management / Politics

Gambatte Ne, Abe-san

Japan’s new prime minister pledged to end his nation’s long-running economic funk, but his planned fiscal and monetary stimulus likely won’t combat Japan’s deep structural issues.

Japan’s political revolving door turned again Sunday, when the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) won a lower-house majority in a snap election. Party leader Shinzo Abe looks set to be the next Prime Minister, giving him his second turn at the helm and Japan its eighth prime minister in as many years.

Abe rallied voters with two pledges: Restoring Japan’s military might and ending its two-decade economic funk, which he vowed to accomplish through massive fiscal stimulus and pressuring the Bank of Japan (BOJ) into “unlimited easing.” While this plan helped win the LDP 294 of the lower house’s 480 seats, it’s not at all likely to lift Japan from its long-running economic morass—and not just because the BOJ’s charter, which enshrines the bank’s autonomy and independence, makes his monetary aims difficult.

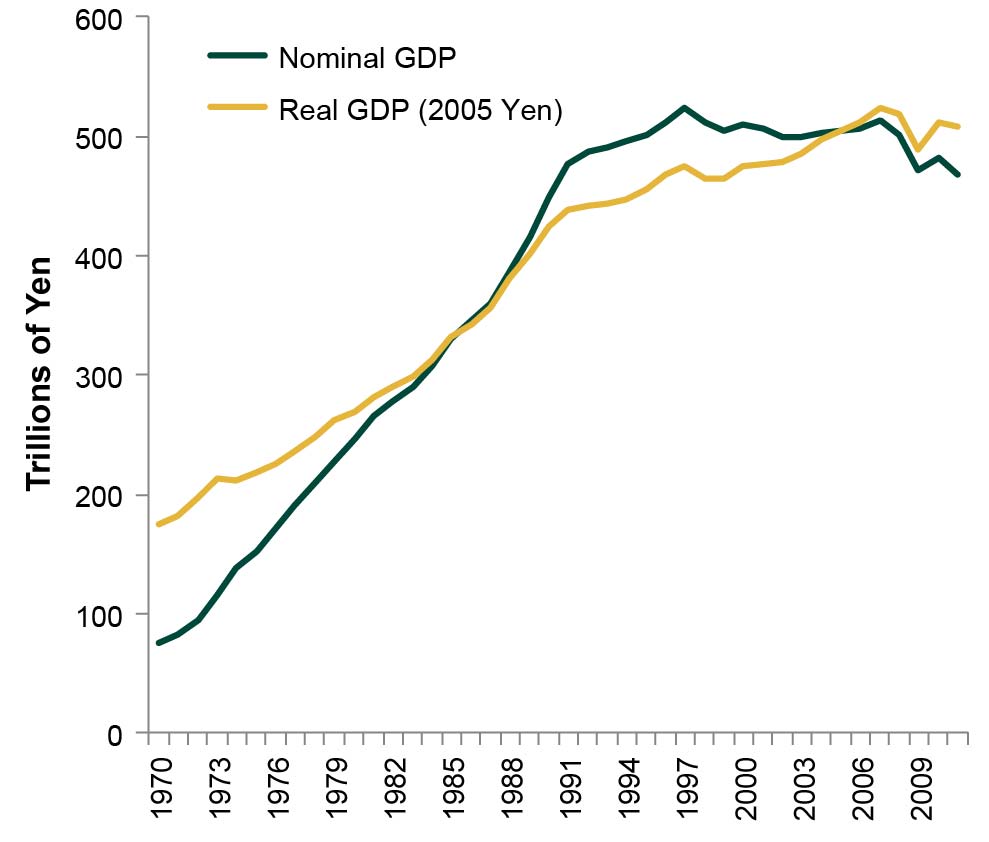

Abe’s prescription assumes Japan’s problems stem from long-running deflation. As the theory goes, 15 years of falling prices and wages have bred a culture of savers, and only higher wages and prices will get folks spending again—if people expect prices to rise, they’re more likely to buy today, but if they expect prices to fall, they’re more likely to wait for a better deal tomorrow. Falling prices and wages certainly play a role in Japan’s economic troubles, but they’re more symptoms of deep structural issues. Fiscal and monetary stimulus, at best, paper over these—something Japan’s demonstrated for years now. The BOJ’s more than tripled the monetary base since 1990, interest rates have been near zero since 1999, and its quantitative easing program is up to roughly ¥67 trillion ($800 billion), or around 14% of GDP. But nominal GDP peaked in 1997, and real GDP has only grown by 6.9% since then, as shown in Exhibit 1.

Exhibit 1: Real and Nominal Japanese GDP

Source: United Nations Statistics Division, as of 12/31/2012.

Meanwhile, prices have continued falling, and wages have fallen even faster, eroding purchasing power. QE bears some blame for this—it’s likely kept prices from falling as much as they otherwise would, but it can’t do anything about falling wages, which are more a function of corporate health.

Japanese industry is dominated by six horizontally integrated conglomerates known as keiretsu, which are organized around banks. Which means, for example, ABC Bank sits at the center, and it owns stakes in ABC Steel, ABC Chemical, ABC Construction, ABC Electronics and ABC You-Name-It—and these subsidiaries own stakes in the bank. These cross-shareholdings make corporate financing easy, but they prevent the unprofitable subsidiaries from failing—banks have a vested interest in keeping them afloat. As a result, banks prop up many unprofitable Japanese firms, crowding out would-be competitors. These firms are in perpetual cost-cutting mode, hence the falling wages. If they were allowed to fail, they’d make room for new competitors, who could be a valuable growth engine over time (i.e., creative destruction). And the banks, finally free of all the unrealized losses, would be able to get their balance sheets in order and eventually lend more freely, further helping combat deflation.

Because of the obvious impacts on employment if these firms fail, however, keiretsu reform is something of a third rail in Japanese politics. And political turnover and bureaucracy have prevented other much-needed reforms since 2006, when former Prime Minister and reform champion Junichiro Koizumi stepped down. The last major reform effort, the privatization of Japan Post, was passed by Koizumi but systematically dismantled by the many governments since his. No leader since has even tried to address items like Japan’s declining workforce, waning productivity and the keiretsu. Some governments have pursued free trade, and Abe has vowed to continue these efforts, but strong political resistance to dropping high agricultural trade barriers has prevented much progress.

Hence, even with the LDP’s strong majority—together with its longstanding ally, New Komeito, it has a supermajority—it’s tough to imagine Sunday’s election being a catalyst for change. Abe doesn’t seem focused on reforming labor markets, immigration, the keiretsu or agricultural trade barriers. Plus, as it did during his first term, Abe’s nationalist agenda may distract him from economic issues. Then, after he succeeded Koizumi, he pursued items like increasing “patriotic” curriculum in Japanese schools while letting the economic reform agenda he inherited lapse. The economy floundered and so did Abe’s approval ratings. His nationalist pledges may have won him some support in this election, which occurred amid a heated territorial dispute with China, but with Japan’s economy back in recession, voters may prove similarly impatient if he spends his time pushing to remove the anti-war clause (Article 9) from Japan’s constitution and boosting Japan’s military presence in Asia while economic conditions deteriorate.

Even if Japan’s long-running economic issues persist though, it can likely still grow over time. The country remains one of the world’s leading exporters and a key link in the global supply chain, and it’s been able to achieve ok growth over the years. There are just several policy steps the government could take to help the economy break through. Policy steps that, for now, still appear unlikely.

If you would like to contact the editors responsible for this article, please message MarketMinder directly.

*The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Fisher Investments editorial staff.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

You Imagine Your Future. We Help You Get There.

Are you ready to start your journey to a better financial future?

Where Might the Market Go Next?

Confidently tackle the market’s ups and downs with independent research and analysis that tells you where we think stocks are headed—and why.