Personal Wealth Management / Market Analysis

Random Musings on Markets XIV: Musings Vs. Mechamusings

Yet another definitely-not-weekly roundup of random and fun financial news. Yes, we think fun financial news is an actual thing.

This Friday’s not-every-Friday financial news roundup brings a tale of a toy store coming back from the dead, the UK’s budget queen, a retrospective on a central bank cartoon, a very special guest musing from our own Chris Wong and more. We hope you enjoy the read!

The Toys ‘R’ Us Kids Are Alright.

Back when Toys ‘R’ Us failed, there was a somewhat popular theory that declining birthrates and demographics were behind its demise—simply, there weren’t enough kiddos to support a giant international toy retailer. Especially in an era where many presume retail in general is inherently dying. We were always skeptical of this narrative, as the store’s revenues had been rather strong in the run-up to its bankruptcy. Moreover, after digging into the details, it became pretty clear Toys ‘R’ Us’s death was a legacy of its leveraged buyout in 2005. In the end, it couldn’t service its more than $4 billion debt load. Just about all of its operating income went to interest payments. Them’s the breaks.

So we were not totally surprised by this week’s news that Toys ‘R’ Us’s creditors have decided to revive it. For reals. They are pursuing “a new, operating Toys ‘R’ Us and Babies ‘R’ Us branding company that maintains existing global license agreements and can invest in and create new, domestic, retail operating businesses.” Unclear, for now, is whether they are planning actual storefronts, or whether it will be an online-only deal like the revived Loehmann’s. But the plan speaks to more than our enduring fondness for Geoffrey the Giraffe. For one, it speaks to the need to fill what The Wall Street Journal called “an $11 billion hole in the toy industry”—a hole that exists because a lot of people actually are still having babies while retail is not dying. It reminds us of when Mother’s Cookies folded during the last recession, then miraculously reappeared in mid-2009 after Kellogg’s bought the brand and revived it. And who can forget Twinkies disappearing after a bankrupt Hostess claimed customers had ditched junk for healthier foods—only for the Great Twinkie Revival of 2013 to disprove that thesis.

So, lesson: Beware sweeping claims about demographic or social trends having various economic impacts. Usually, there is something else afoot.

Dancing Queen or Budget Queen?

UK Prime Minister Theresa May’s Conservative Party conference speech was one for the ages. She cracked jokes about her coughing fit and the falling backdrop during last year’s speech. She took the stage with a little dance while Abba’s “Dancing Queen” played over the PA, a fun little callback to her impromptu dancing in Africa this summer, which went viral.[i] Oh, and to great fanfare, she announced that she is going to end austerity. Full stop. “Spending cuts” are over!

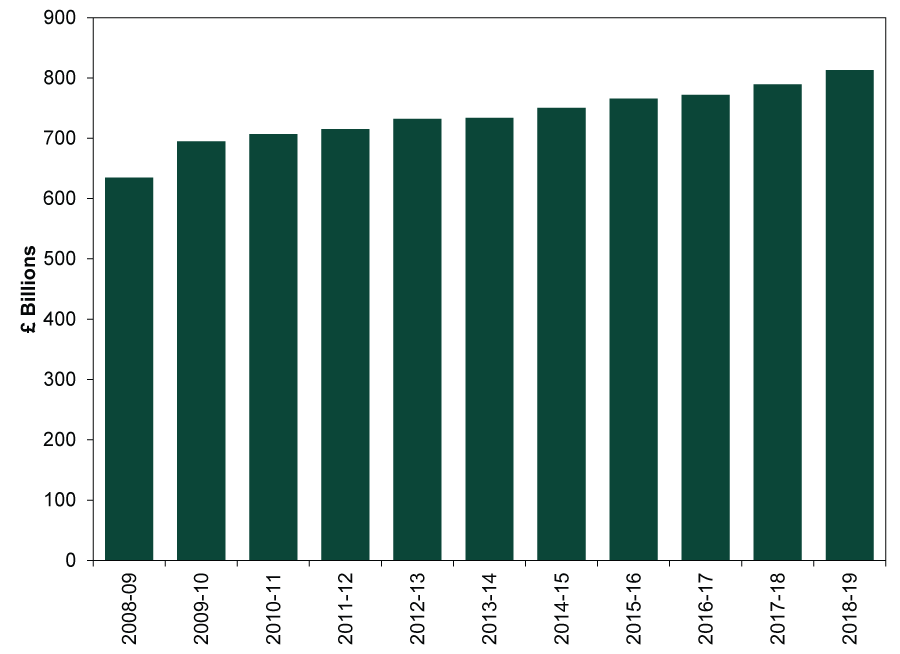

We have long been amused by the UK’s alleged austerity program, as we have never found evidence it actually happened. You see, while politicians assure us the country has spent the last decade under an austere regime of spending cuts and grey skies, spamwiches and meatloaf, Her Majesty’s financial statements show spending didn’t actually fall. Exhibit 1 shows total public spending hasn’t fallen once since austerity allegedly began in 2010. There was one year when it fell -0.2% on an inflation-adjusted basis, but if you have to use statistical fudging to get the austerity to appear, calling it austerity seems a stretch.

Exhibit 1: What Austerity?

Source: HM Treasury, as of 10/3/2018. Figure for 2018-19 is the Treasury’s current plan.

The Treasury did cut its budget, as in, spend less than it originally planned to when mapping long-term spending. But that isn’t an actual spending cut. If Elisabeth spent $150 on hand-painted yarn at Stitches West in 2017, planned to spend $300 at the convention this year but ended up spending only $200, she did not enact a yarn spending cut. She simply changed her mind and ended up with a smaller-than-planned spending increase. That is not yarn-austerity. It is yarn spending growth. Which means we didn’t buy all the “austerity is killing the UK economy” commentary from several years ago, and we don’t buy the “ending austerity will endanger the UK economy” that is starting to pop up now.

About That Bernank…

“I Created ‘The Bernank’ on YouTube. And I Was Mostly Wrong.” is the title of a New York Times op-ed this week, penned by the creator of a viral, comedic 2010 video “explainer” on quantitative easing, the Fed’s now-concluded long-term bond buying program.

The cartoon argued QE was a negative policy launched by the continually failing Fed that would exacerbate inflation through “money printing,” benefiting banks (especially one that rhymes which Oldman Knacks) by bidding up Treasury prices and then buying them high. It is a harsh critique of Fed policy, to be sure. And now it seems the creator thinks he was wrong.

The admission is refreshing! And we agree, by the way, the cartoon was wrong. But not for the reasons the article now argues: that QE was beneficial in stabilizing the economy but failed to benefit lower income and “underbanked” Americans—those without access to financial services. We mean, it did fail to benefit them. But that is largely because, in our view, QE failed everyone. You see, we don’t think QE was stimulus to begin with. It didn’t stabilize the economy, either. Far from enriching shareholders, we think stocks have risen in spite of QE.

Here is why: Inflation is a monetary phenomenon in which too much money chases too few goods and services. To get it, money supply must grow. And that takes lending, given America’s banks create most money supply. To do so, banks borrow from the public (think: savings accounts, checking accounts) and other banks. They use this to underpin long-term loans to fund car purchases, housing, business investment and more. Converting short-term money into long is banks’ societal function—their raison d’être, in fancy speak. They are paid for this function based on the difference between short-term interest rates (their funding cost) and long-term interest rates (their loan revenue).

When the Fed launched QE, short-term rates were near zero. Fed bond buying lowered long rates, slimming the difference between the two. In econo-speak, this is called flattening the yield curve. It reduces banks’ loan profits. And it usually coincides with less lending and slower economic growth. The policy’s likely end was the reverse of the claim. It wasn’t inflationary; it was disinflationary.

The funny thing now, in our view, is that the evidence for all this—and the theory—has been staring investors in the face for years. Just consider one point: For most of this year, the media has been wringing its hands over the flattening yield curve, fearing it means recession looms. Yet they just spent the bulk of the last decade telling us a policy that expressly targeted a flatter yield curve was economic rocket fuel. The contradictions here are many and varied.

Apologies That We Aren’t a Podcast and Don’t Have a Discount Code

Here is a thing we hear now and then: With big brands so entrenched and ginormous conglomerates controlling the market, competition is dying. Obviously, the craft beer industry disagrees. So do all the independent record and bookstores who outlasted Borders, Tower Records and Virgin Megastore. And if you have ever listened to a podcast, you might know a litany of upstart mattress makers, energy bar manufacturers, clothing subscription services and online markets that disagree competition is dead.

This was the subject of a nifty Wall Street Journal piece about the rise of “microbrands” taking big bites out of consumer markets that the big names long dominated. They did it with cheap advertisements on social media and podcasts, building cult followings with a few testimonials and well-targeted market research. To show how it works, the author launched a fake coffee startup and learned the best practice is to advertise before you even launch, so you can gauge initial demand via pre-orders and set production targets accordingly. Then you automate and outsource every possible part of the process, wrap your product in snappy yet minimalist packaging, and go to town.

What makes this all work is the simple fact that ads are dirt-cheap and easier than ever to target. Casper doesn’t need to spend a huge chunk of change on a glossy ad in a lifestyle magazine showing impossibly gorgeous people lounging on a cushy bed with the fanciest sheets—it can just get Matt Mira and Doree Shafrir to rave about their in-laws’ Casper mattress during an ad break on Matt and Doree’s Eggcellent Adventure. Bonobos doesn’t need to splurge on full spreads in the GQ fall fashion issue—they can get Adam Scott Aukerman to crack some jokes while singing their shirts’ praises in between segments on U Talkin’ U2 to Me. For the advertiser, if it is a popular podcast, it might cost a few hundred bucks, plus whatever they will lose on the free shipping or discount they offer listeners. That is probably a heck of a lot cheaper than the six figures they might pay for a full-page ad in a major magazine—and it has a more immediate call to action.

So next time you hear competition is dead, patiently explain to your conversation partner that advertising has come a long way since “Mail Kimp Girl” was an inside joke among Serial fans, and anyone can take a shot at disrupting a market as long as they have a snappy name and a few hundred bucks for advertising.

Countries Must Do Their Due Diligence, Too (A Special Guest Musing by Chris Wong)

We occasionally comment on financial fraud stories in order to reiterate an important lesson: If it sounds too good to be true, it usually is. Healthy skepticism can go much further in protecting investors’ hard-earned money than regulators’ best efforts. However, this advice doesn’t apply only to mom and pop investors—it seems … umm … monetary officials may need a reminder, too!

According to The Wall Street Journal, an “‘Ocean’s Eleven’-style cast of characters” almost defrauded the African nation of Angola’s central bank out of $500 million in 2017. When that type of change is involved, you might think the perpetrators concocted an elaborate scheme straight out of a James Bond movie. Indeed, the caper involves forged documents, high-stakes meetings and corrupt officials. But at its core, the scheme was relatively basic: The scammers convinced Angolan government representatives to hand over millions for the purposes of diversifying into an account the central bankers didn’t control and wasn’t in their name. (The “investors” took custody of the assets.)

Angola’s lawyers say the country may have fallen victim to a decades-old type of get-rich-quick scheme, typically used to defraud individuals or companies, not sovereign states. Investors are told they can make huge returns through a private market in ‘bank guarantees.’ There is no such market, and the U.S. Treasury Department and Securities and Exchange Commission have warned that such offers are always fraudulent.

How did the authorities catch wind of the shady business? Not through sophisticated spy work or advanced surveillance technology. Rather, when the suspected shysters tried transferring the cash from HSBC to an outside account, an alert bank teller[ii] smelled something fishy and raised the issue to management, which then suspended the account for review. Take heart that in a world where technology seems to be replacing many daily operations, human judgment still matters.

This Week’s Test Didn’t Include Cat Pictures

Those of you with cell phones—which, come on, is like everybody at this point, especially if you are reading this online—may have shared an odd experience with us and the rest of Americans this week: Wednesday’s “Presidential Alert” text message.

We figure you already know THIS WAS A TEST of the National Wireless Emergency Alert System, and no action was needed. But you may not have known of the government’s fascinating, decades-long quest to build such a system. Thankfully, Wired shared this in a really fun article we enjoyed Thursday.

Since the 1950s, it seems government has been attempting to find a solution to warn the populace in the event a nationwide calamity—think nuclear war here, people—looms. The plans varied from Dwight Eisenhower’s special radio stations’ broadcasting a then-popular television star’s public service announcement (PSA), reassuringly noting most Americans would survive, to a wacky buzzer that plugged into outlets the government set off via electrical surge. They even tested this thing in small-town Michigan by having households release pink balloons if their device buzzed.

Our favorite? The 1970s-era Decision Information Distribution System (DIDS). The system involved government-controlled boxes that attached to your television, triggered by low-frequency radio waves. In the event of an emergency, the radio waves alerted the box, which turned the television on and tuned it to a PSA. Per Wired:

The government branded the program—which it estimated would save the lives of 27 million Americans by providing immediate warning of a Soviet attack—with PERki, a peppy, friendly puppy mascot emblazoned all over its literature.

We guess fluffy puppies make even potential nuclear holocaust more palatable? Who knew. (It wouldn’t work on us.) Anyway, the system apparently “worked,” and the feds planned an expansion until they ran into trouble: Watergate. It seems folks grew a little reluctant to have a government-controlled box in their house after the little matter of bugging directed by federal officials.[iii] Hence, you don’t get PERki, you just get a text from Trump. Hey! An idea: Next time the text warning should have a cat picture.

Anyway, the Wired piece is really just a fun read for your weekend. But it is also a story about how technology has changed our lives, solving a 60-year old government problem along the way.

Enjoy your weekend!

[i] We would like to officially request a dance-off between May and Ed Balls, former Shadow Chancellor and Strictly Come Dancing contestant extraordinaire.

[ii] Mad props to this teller for doing her job and following protocol—a vastly underrated quality, if our experience is any indication.

[iii] We guess even puppies can’t make government bugging palatable.

If you would like to contact the editors responsible for this article, please message MarketMinder directly.

*The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Fisher Investments editorial staff.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

You Imagine Your Future. We Help You Get There.

Are you ready to start your journey to a better financial future?

Where Might the Market Go Next?

Confidently tackle the market’s ups and downs with independent research and analysis that tells you where we think stocks are headed—and why.