Personal Wealth Management / Economics

Takeaways From China’s Historic Q1 GDP

What the latest Chinese economic data reveal about what lies ahead.

Editors’ Note: MarketMinder doesn’t make individual security recommendations. Any reference to an individual publicly traded firm herein is merely included to illustrate a broader point.

China’s latest economic data dump received a lot of press, especially its eye-popping Q1 GDP growth rate. Many also noted China’s economic recovery would likely slow in the coming quarters—a return to its pre-COVID normal—which we think sounds about right and should be fine for stocks. In our view, Chinese economic figures remain a useful, albeit imperfect, preview of post-pandemic life in the US and other developed nations—a helpful way for investors to set their expectations for other major economies’ data.

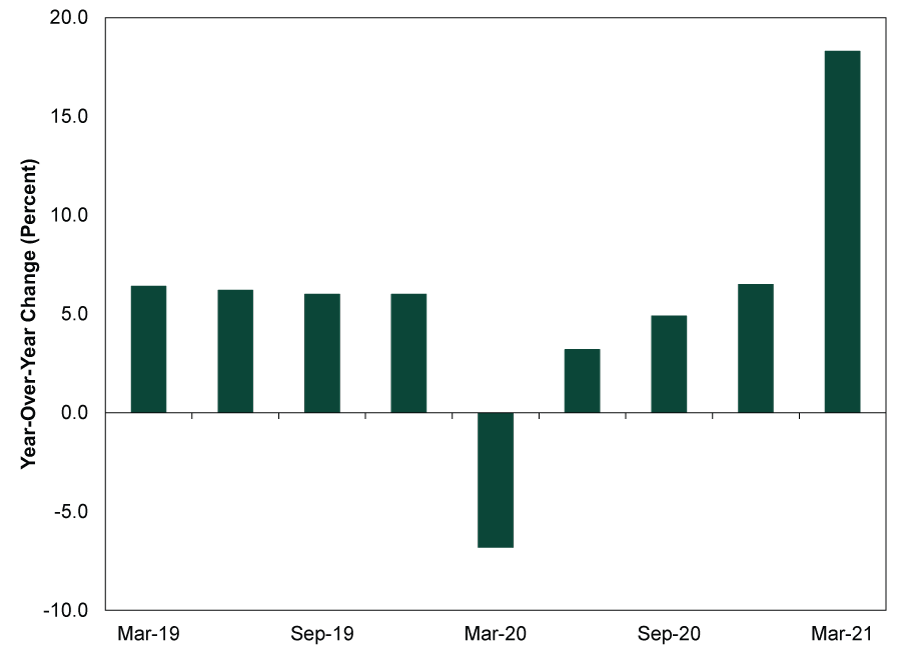

Chinese Q1 GDP soared 18.3% y/y, a bit slower than some economists’ expectations, but still the fastest growth rate since the country began reporting quarterly GDP in 1992.[i] (Exhibit 1)

Exhibit 1: Chinese GDP’s Historic Q1

Source: FactSet, as of 4/16/2021. Chinese GDP, year-over-year percentage change, quarterly, Q1 2019 – Q1 2021.

However, the historic reading reflected last year’s events, not unprecedented economic output. We are referring to the base effect—a concept we have highlighted in recent commentary—which skews results when the year-over-year reference point has a large, temporary rise or fall. That reference point is the denominator in the year-over-year growth rate calculation, and since COVID lockdowns are about a year old, it is skewing data higher in a major way. Even if the numerator (the present) doesn’t change much, a sharply lower denominator will inflate the results for a spell.

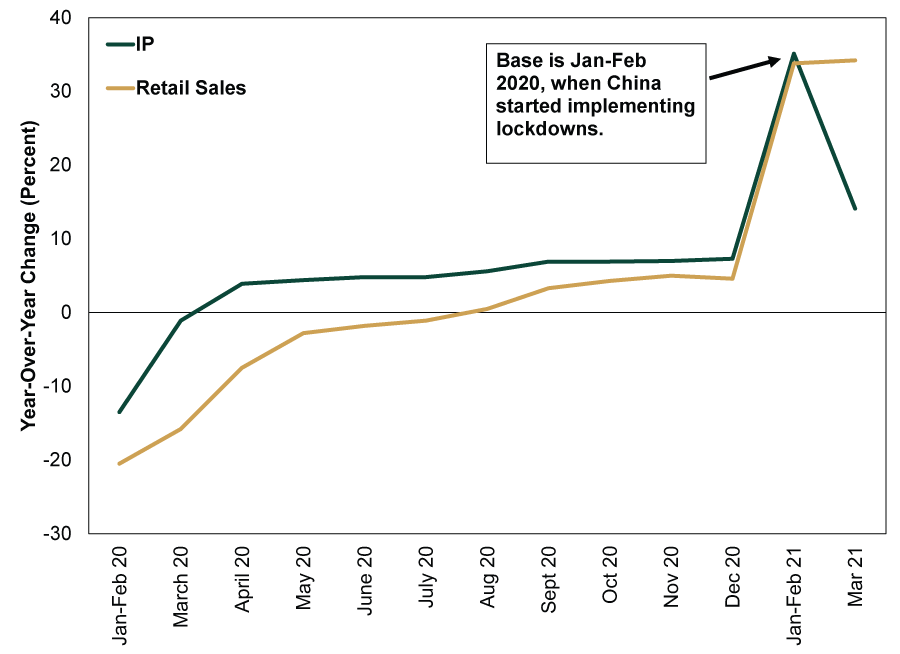

This affects readings most in Emerging Markets like China that report most economic data on a year-over-year basis. Because China started implementing lockdown measures in January 2020—about two months before most of the developed world—the base effect showed up there first. Industrial production jumped 35.1% y/y in January and February before slowing to 14.1% in March, while retail sales soared 33.8% y/y in January and February and sped to 34.2% in March.[ii] (China’s National Bureau of Statistics [NBS] combines January and February data to remove the base effect skew from the Lunar New Year’s variable timing.) These huge growth rates mostly reflect a depressed, smaller base due to China’s most severe COVID restrictions in place from late January to early March. (Exhibit 2)

Exhibit 2: The Base Effect’s Impact on Monthly Data

Source: National Bureau of Statistics, as of 4/16/2021.

Many analysts acknowledged the base effect’s impact on the Q1 GDP reading, and looking ahead, they anticipate growth will slow in the coming quarters, continuing a longer-term trend. One research outfit estimates Q1 GDP grew about 5.4% after stripping out the base effect, somewhat slower than the pre-pandemic trend of 6%.[iii] Others cited Q1 GDP’s seasonally adjusted 0.6% q/q rise, a pretty marked deceleration from Q4’s 3.2% q/q.[iv] Now, many experts don’t trust these data, arguing the NBS has kinks to work out with its seasonal adjustment methodology. However, the focus on recent slower growth is notable, in our view.

We agree Chinese economic growth is likely to slow in the coming quarters—policymakers have telegraphed as much. The government set expectations for slower growth at March’s National People’s Congress meeting, aiming for “above 6%” annual growth for 2021—a target with plenty of leeway. The government also reiterated its desire to contain financial risks and maintain financial stability. That means tamping down on credit growth—and March data suggest this is happening.

Total social financing—a broad credit gauge that encompasses loans and funding to the private sector from state-owned lenders and the shadow banking realm—slowed by a percentage point in March to 12.3% y/y from February’s 13.3%.[v] While a high base effect from last year’s COVID relief measures played a role, the government has also been telling financial institutions to tap the brakes on credit growth and focus on stability. At the Financial Stability and Development Committee’s April meeting, the government told small, local financial institutions to avoid “excessive” growth—a message reiterated by the central bank to big lenders.[vi]

In our view, this isn’t a negative—nor does it mean growth in the world’s second-largest economy is about to halt. Rather, we think it signals a return to normal. The Chinese government has long sought to get the country’s opaque shadow banking sector in order while allowing greater financial liberalization—all while maintaining economic stability. This process has gone in fits and starts, and after a brief pandemic-related pause, policymakers appear to have reprioritized these efforts.

Consider a Chinese “bad bank”—i.e., a financial institution created to clean up bad debt of big state-owned lenders—in headlines recently. China Huarong Asset Management Co., whose former chairman was recently executed due to bribery, failed to release 2020 financial statements in early April. Some ascribed the delay to a possible restructuring, prompting speculation the government could allow the state-backed institution to fail[vii]—the most consequential default in over 20 years, according to some observers.[viii] Financial regulators’ comments last Friday seem to have quieted those concerns for now, but in our view, this saga highlights the government’s emphasis on getting financial bloat under control, whether among private or state-owned lenders. This return to the pre-pandemic priority of stabilizing the financial system suggests to us that the broader economic recovery is well underway.

In our view, China provides a rough snapshot of what the Western world can expect the further we get from the pandemic. Now, most developed economies aren’t command economies. COVID experiences are different, too, as regions face unique outbreak challenges. But as developed countries begin to reopen thanks to a combination of recovered immunity, vaccine immunity and herd immunity, we expect them to soon return to their pre-pandemic trends. As China is now showing, that likely means slower growth ahead—not an acceleration—another sign this bull market is likely more late-cycle than early-cycle, in our view.

H/T: Fisher Investments Research Analyst Austin Fraser

[i] Source: FactSet, as of 4/16/2021.

[ii] Source: National Bureau of Statistics, as of 4/16/2021.

[iii] “Chinese Economy Grew More Than 18% in First Quarter,” Jonathan Cheng, The Wall Street Journal, 4/16/2021.

[iv] See note ii.

[v] Source: FactSet, as of 4/13/2021.

[vi] “China Flags Deeper Clampdown on Debt Growth at Local Banks,” Staff, Bloomberg, 4/8/2021.

[vii] We guess that would make it a bad-bad bank? Or is that what one would call the new bad bank that takes over the old bad bank’s assets?

[viii] “Why China ‘Bad Bank’ Huarong’s Fall Is Big Bad News,” Rebecca Choong Wilkins, Bloomberg, 4/17/2021.

If you would like to contact the editors responsible for this article, please message MarketMinder directly.

*The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Fisher Investments editorial staff.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

You Imagine Your Future. We Help You Get There.

Are you ready to start your journey to a better financial future?

Where Might the Market Go Next?

Confidently tackle the market’s ups and downs with independent research and analysis that tells you where we think stocks are headed—and why.