Personal Wealth Management / Market Analysis

Volatility and Manufacturing

Headlines about US and Chinese manufacturing reports seemed to rankle investors Monday, but the actual data reports were benign.

Global market volatility continued Monday, with the S&P 500 falling around -2.3% and most European and Asian indexes down, too. Headlines were quick to blame January manufacturing reports, which showed slowing activity in the US and China. It’s impossible, in our view, to say with certainty why stocks fall on any one day. Markets are just volatile. Growth jitters were widespread, but so were continued fears of currency volatility in some Emerging Markets, and Treasury Secretary Jack Lew redoubled his efforts to goad Congress into raising the debt ceiling before the February 7 deadline (warning of default). Investors had any number of things to chew over—and they might chew for a while longer. But whether or not volatility continues—and whether or not we get a full-blown correction—the fundamentals remain in place for this bull market to continue.

This might be tough for folks to believe, however, given the way headlines portrayed US and Chinese manufacturing. Few bothered mentioning both still grew! Instead, China was a “drag on the global manufacturing revival.” The US “declined more than forecast,” with new orders “reeling.” If you didn’t read past the lede, you’d think a global recession had started.

Blame it on how these manufacturing reports are constructed. These and the many other manufacturing reports released in recent days are Purchasing Managers Indexes, aka PMIs. Every month, the purchasing managers at manufacturing firms complete a survey, reporting whether output, new orders, export order, employment, costs, inventories and the like are rising or falling. The number reported is the percentage of purchasing managers reporting higher activity. If fewer than 50% report growth, the surveys assume the industry is contracting. If more than 50% of firms report growth, then it’s an expansion—so any reading above 50 is considered growth. Even if the headline number falls from 56.5 to 51.3, as the US’s ISM Manufacturing PMI did, it’s still growth—just at a slower rate. But many outlets reporting a decline in the ISM index buried this distinction.

The same applies to the New Orders subindex of the ISM survey—widely regarded as its most forward-looking component, as today’s orders become tomorrow’s production. In December, the New Orders subindex hit 64.4—the highest since August 2009, fresh off the recession’s low. In January, it slowed to 51.2—a big drop in the index level, but still indicating a rise in new business, albeit a slower one. Even if it were a contraction, it wouldn’t necessarily mean a downturn is around the corner. The New Orders subindex was below 50 in five of the past 20 months. The US economy grew all the while.

It’s a similar story in China. The official manufacturing PMI slowed to 50.5—still growth. New Orders slowed to 50.9—still growth. Both contracted multiple times in 2012, yet China still grew 7.8% that year. Plus, slower factory growth isn’t surprising or a sign of broad weakness. Chinese authorities have been quite vocal about their efforts to force firms to cut steel production in order to combat a supply glut. When their strong verbal urging didn’t work, authorities started destroying blast furnaces at the offending firms. Now, with output growth slowing, we’re seeing the fruits of their efforts.

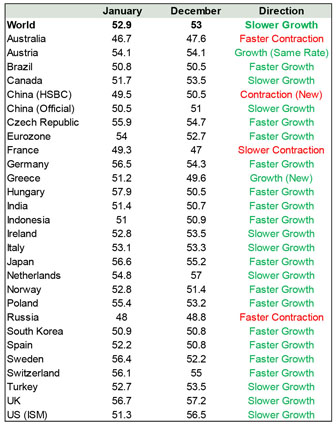

While manufacturing in China and the US is still growing, what matters even more is how the entire world is doing. Through Monday, 26 countries and the eurozone have released January manufacturing PMIs, and JP Morgan has released its global manufacturing PMI. As shown in Exhibit 1, only four are in contraction—Australia, France, Russia and China’s HSBC survey, which captures the small, private firms victimized by the crackdown on shadow lending, as we discussed here. Fourteen countries showed faster growth. Greece grew for the first time in 53 months. This doesn’t square with the notion of a weak world.

Exhibit 1: Global Manufacturing PMIs at a Glance

Sources: FactSet, Markit Economics, ISM, Reuters.

Then again, the heightened focus on manufacturing obscures a larger point: Manufacturing isn’t the whole economy, and it isn’t a leading indicator—it can and does diverge from broader growth. Manufacturing gets a lot of eyeballs as one of the first monthly economic reports released, but in most of the developed world and even China, the service sector is a much bigger component. China’s non-manufacturing PMI, released Sunday, hit 53.4, indicating service firms are growing faster than factories. Markit’s Flash PMI for the US’s service sector accelerated in January, from December’s 55.7 to 56.6. The eurozone Flash PMI showed continued growth in services, too.

Over the medium and longer term, this is what markets weigh—fundamental economic reality. In the short term, emotions rule, and stocks can swing wildly, just as they did on Monday and in January.

When stocks fall hard in the short term, take a deep breath, and take a look at what’s going on in the world—ask yourself if reality warrants a steep drop. Take that look today, and in our view, you’ll see it doesn’t. The latest GDP reports show 2013 ended on an upswing. All the manufacturing and service PMIs out so far indicate growth continued in January. Eleven of the Conference Board’s 13 Leading Economic Indexes (LEI) are rising (Korea was flat and Mexico fell -0.1%)—recessions typically don’t begin until LEI has fallen for some time. A high and rising LEI trend usually means growth continues. And with economic growth comes earnings growth—the 251 Q4 earnings reports in through January showed aggregate S&P 500 earnings per share up 7.9% y/y, accelerating nicely from Q3. The political climate is favorable—competitive advanced economies are gridlocked, and free market reforms continue in several developing nations.

These fundamentals have given us nearly five years of bull market. Nothing changed Monday except for investors’ perceptions. Sometimes, folks are just more prone to look for the bad than the good. Skepticism and optimism are still playing tug-of-war, and skepticism is winning today. But this isn’t bad—resurgent skepticism helps lower expectations, making the proverbial wall of worry that much higher. This volatility, though painful and tiresome for investors, is normal and healthy in bull markets—and fundamentals point to more bull ahead.

If you would like to contact the editors responsible for this article, please message MarketMinder directly.

*The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Fisher Investments editorial staff.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

You Imagine Your Future. We Help You Get There.

Are you ready to start your journey to a better financial future?

Where Might the Market Go Next?

Confidently tackle the market’s ups and downs with independent research and analysis that tells you where we think stocks are headed—and why.