Personal Wealth Management / Market Analysis

Why Turkey's Currency Kerfuffle Isn't Likely to Prove a Global Crisis

Despite the latest twists and turns, Turkey’s crisis still shouldn’t ripple globally.

Turkey’s currency crisis has taken some fresh turns in recent days, finding new ways to spook investors globally. First President Trump doubled steel and aluminum tariffs against Turkey—a move that was probably more political than economic, despite its official purpose of compensating for the lira’s decline. In response, the lira plunged about 13% on Friday, sparking fears European banks with Turkish exposure were at risk.[i] Eurozone Financials thus took it on the chin Friday and Monday, dropping -4.9% across those two trading days.[ii] But by Tuesday, the focus shifted to India, as the rupee plunged to a record-low of about 70 per dollar, sparking fears of a contagion rippling throughout Emerging Markets (EM).[iii] Our viewpoint on this saga hasn’t changed. Turkey’s problems are still uniquely Turkish, and there is little fundamental reason for other EM nations to follow its downward spiral. Turkey might keep knocking sentiment, which can spark short-term volatility, but over time, we expect markets to weigh fundamentals.

While investors’ laser focus on Turkey is somewhat new, its problems aren’t. As we explained in more detail back in May, it has steadily slipped into authoritarianism since President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan first became Prime Minister in 2003. Lately, he has taken to arguing high interest rates cause inflation and heaping political pressure on the (still nominally independent) central bank to avoid hiking interest rates—even as the lira plunged this year. After winning June’s election, which made him Turkey’s first President with real power, he transferred most powers from parliament to the presidency and installed his son-in-law as Finance Minister, raising fears of more intervention and haphazard economic policy. This, combined with the specter of diminishing central bank independence, has caused foreign investors to rapidly lose confidence and pull their money out. That tanked the lira, creating a thorny situation for Turkish companies that borrowed in dollars or euros in recent years. Stepped-up US sanctions and tariffs have added fuel to the fire in the short term, but the lira’s woes have much more to do with Erdogan’s warped economic viewpoints.

Other EM nations have their fair share of political risk, but none are backsliding into authoritarianism or meddling with monetary policy to the degree Turkey is—not even close. Overall and on average, most are trending toward stronger political institutions and more independent central banks. There are a couple notable exceptions, such as South Africa, where uncompensated land expropriation and public ownership of the central bank are both on the government’s docket. Thailand still has a military junta following a 2014 coup. But these cases are the exception, not the rule.

One popular portrait of a currency crisis contagion paints speculators as the catalyst, claiming that when problems arise in one country, they start looking for the next domino to fall and placing currency bets accordingly.[iv] You might have read that “speculators” brought down the Asian tigers in 1997, forcing South Korea, Thailand and Malaysia to seek bailouts—and very nearly taking down a few others. But this narrative glosses over deep-seated fundamental issues. Speculators don’t bet against currencies for no reason. They do so when they have fundamental reasons to believe the currency is due for a plunge. In the Asian Currency Crisis, they saw nations with currency pegs, low foreign exchange reserves and a high load of dollar-denominated debt—and they saw the dollar strengthening against most major floating currencies. This gave them reason to believe the governments would spend down forex reserves to maintain the peg but eventually have to throw in the towel, bringing a sudden devaluation that would make US dollar-denominated debt nigh-on impossible to service.

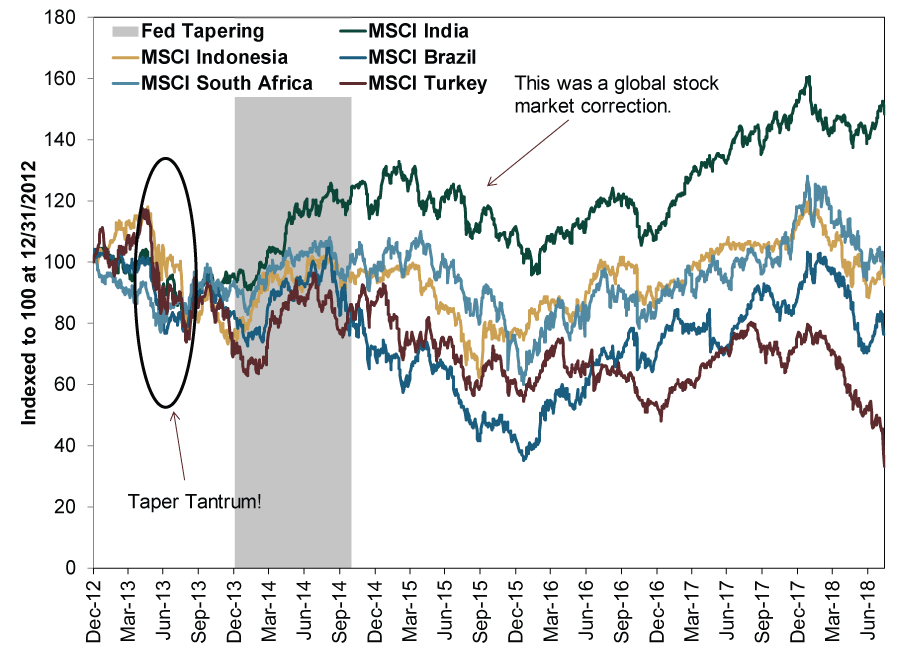

So the question to ask today is, do speculators have fundamental reason to expect full-blown crises in most other EM nations? We doubt it. Take India, the nexus of Tuesday’s sour sentiment. India is a thriving democracy with separation of powers and an independent central bank with internationally respected leadership and a long stretch of overall rational decision-making. It hasn’t been shy about raising interest rates when needed to combat inflation. On the economic front, India’s foreign exchange reserves as a percentage of foreign currency debt are the fourth-highest in EM, while its loan-to-GDP ratio has barely budged since 2010 (Turkey’s has soared). It seems to us that investors are overreacting because India was once famously branded as one of the “fragile five” economies in 2013—a snappy phrase for “five countries with higher current account deficits, which a couple analysts think are super vulnerable to a stronger dollar.” The Fed’s “tapering” of quantitative easing was supposedly an outsized risk to these nations, sparking a “taper tantrum” of volatility after then-Fed head Ben Bernanke first alluded to tapering QE in late May 2013. But that was a short-lived freakout. Once the Fed actually tapered and ended QE in 2014, it didn’t pull the rug out from India or its fragile five brethren (Indonesia, Brazil, South Africa and Turkey).[v]

Exhibit 1: Tapering QE Didn’t Doom the “Fragile Five”

Source: FactSet, as of 8/14/2018. MSCI India, MSCI Indonesia, MSCI Brazil, MSCI South Africa and MSCI Turkey net returns in USD, 12/31/2012 – 8/13/2018. Indexed to 100 at 12/31/2012.

Some observers point to higher oil prices and the potential for higher government spending in the run-up to next year’s election as potential triggers for future Indian weakness. We’ll partially concede the point on oil prices, as India does import most of its energy. At the same time, oil is also still cheaper today than it was throughout most of this decade’s first half, which was a fine time for India’s economy. As for the government spending angle, India’s government projected a deficit of 3.5% of GDP for fiscal 2018/2019. The IMF estimates India’s debt at 67% of GDP. Neither figure is consistent with a brewing debt crisis.

As for eurozone banks’ vulnerability to distressed Turkish debt—the other alleged contagion mechanism—this too seems overestimated. While some do have exposure to Turkish banking investments, banks generally hedge for currency risk. Not doing so in Turkey’s case would be extremely bizarre in light of the country’s long-running, well-known problems. Global banking circles have been watching Turkey turn into a basket case for years. While it is impossible to know exactly how much each actual loan is hedged, the amount of Turkish foreign exchange loans not matched by foreign exchange deposits as a percentage of total loans is only 22%—near all-time lows.[vi] For frame of reference, when Turkey last had a currency crisis in 2002, they had an inherently unstable fixed currency peg (not the case today) and foreign currency loans not matched by deposits were far higher, around 75% of total loans.[vii] So the systemic risk is lower today—and Turkey’s woes didn’t go global in 2002.

It wouldn’t shock us if volatility lingered a bit longer or resurfaced later on, depending on how the political situation develops (and whether Erdoğan and Trump continue their verbal tussle). But just as the last three big EM currency crises (Asia in 1997, Mexico in 1994, South America in the late 1980s) didn’t cause global bear markets, we don’t think Turkey has the power to do so today.

[i] Source: FactSet, as of 8/14/2018.

[ii] Source: FactSet, as of 8/14/2018. MSCI EMU Financials Index return with net dividends in USD, 8/9/2018 – 8/13/2018.

[iii] Source: FactSet, as of 8/14/2018.

[iv] We don’t usually refer to markets with gambling language, but in this case it is necessary, as we are referring to actual speculative bets.

[v] Not that all went swimmingly in these nations. South Africa had to deal with the commodities downturn and the scandals surrounding now-former President Jacob Zuma. Brazil dealt with the same commodities crash, which caused a local recession, and a political scandal called Operation Car Wash, which resulted in the impeachment and removal of President Dilma Rousseff. And, of course, Turkey had its issues. But these were all local phenomena, not category-wide weaknesses.

[vi] Source: Bank for International Settlements, as of 8/10/2018.

[vii] Ibid.

If you would like to contact the editors responsible for this article, please message MarketMinder directly.

*The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Fisher Investments editorial staff.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

See Our Investment Guides

The world of investing can seem like a giant maze. Fisher Investments has developed several informational and educational guides tackling a variety of investing topics.